How Early Wins Can Become Missed Fortunes in the Pro-Rata Trap

Dive into the tricky game of pro rata and learn more about why investors don't always exercise their rights and sometimes miss out big.

Some of the biggest missed fortunes in venture capital don’t come from saying no. They come from saying yes — and then disappearing.

You spotted the rocket ship early. You wrote the first check. And when it started to take off... you got left behind.

This is the pro-rata trap: when early-stage investors don’t follow on in their best companies, and their stake quietly shrinks round after round.

It’s not enough to bet on the next Stripe. You have to stay in long enough to win.

Here’s how good investors end up losing — and how the best ones are adapting 👇

Brought to you by Eilla AI - The Most Advanced Private Company Search is Here!

Meet Hunter, Eilla’s AI Scout. No more keyword guessing and sifting through lists with 100s of irrelevant companies. Just describe what you're looking for and let Hunter do the rest.

How it works:

Turn any description into a shortlist: Describe your ideal company and Hunter finds the exact matches based on product, features, target group and more.

Dig deeper with multi-source data: Get in-depth insights on 9m companies using data from Capital IQ, Crunchbase, LinkedIn, SimilarWeb and more.

You don’t need to write the biggest check — but you do need to keep showing up.

Because in venture, the second and third checks often matter more than the first.

This article unpacks:

What the pro-rata trap really is

The Uber case study no one talks about

How funds like Lowercase won big while others sat out

The math behind dilution (and how $100M+ is quietly lost)

Why early funds hesitate — and how newer ones are fixing it

And ultimately, why your early conviction only pays off if you're willing to back it again and again.

1. What Is The Pro Rata Trap In Venture Capital?

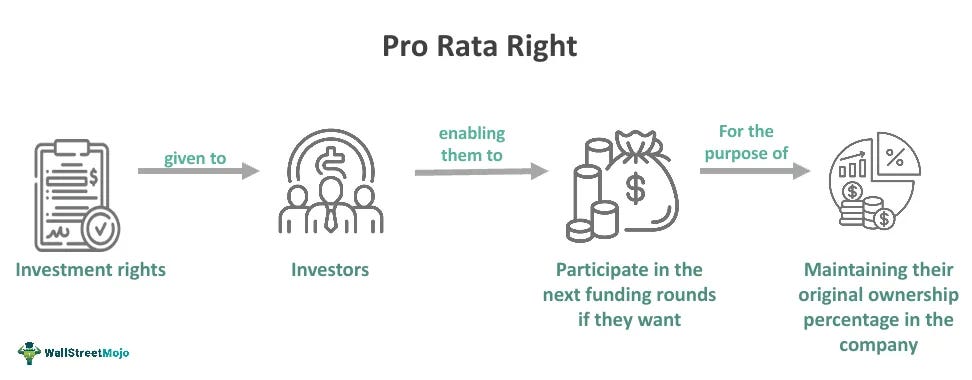

Pro-rata rights give investors the option to maintain their ownership stake in a company as it raises future funding rounds. If you own 5% after the seed round, pro-rata lets you write a check in Series A to keep that 5% instead of watching it shrink.

These rights are standard in most priced rounds, but the catch is that you have to use them. And that’s where the trap kicks in.

The pro-rata trap is what happens when early investors don’t follow on with their best companies. Sometimes they can’t afford to. Sometimes they misjudge the upside. Sometimes they pass for strategic reasons and regret it later. Whatever the reason, the result is the same: your ownership gets diluted, and the upside you helped create gets captured by someone else.

Plenty of early-stage funds fall into this exact dilemma. They got in early. They backed a rocket ship. But when it came time to double down, they held back and left life-changing returns on the table.

2. Uber’s Early Investor Case Study

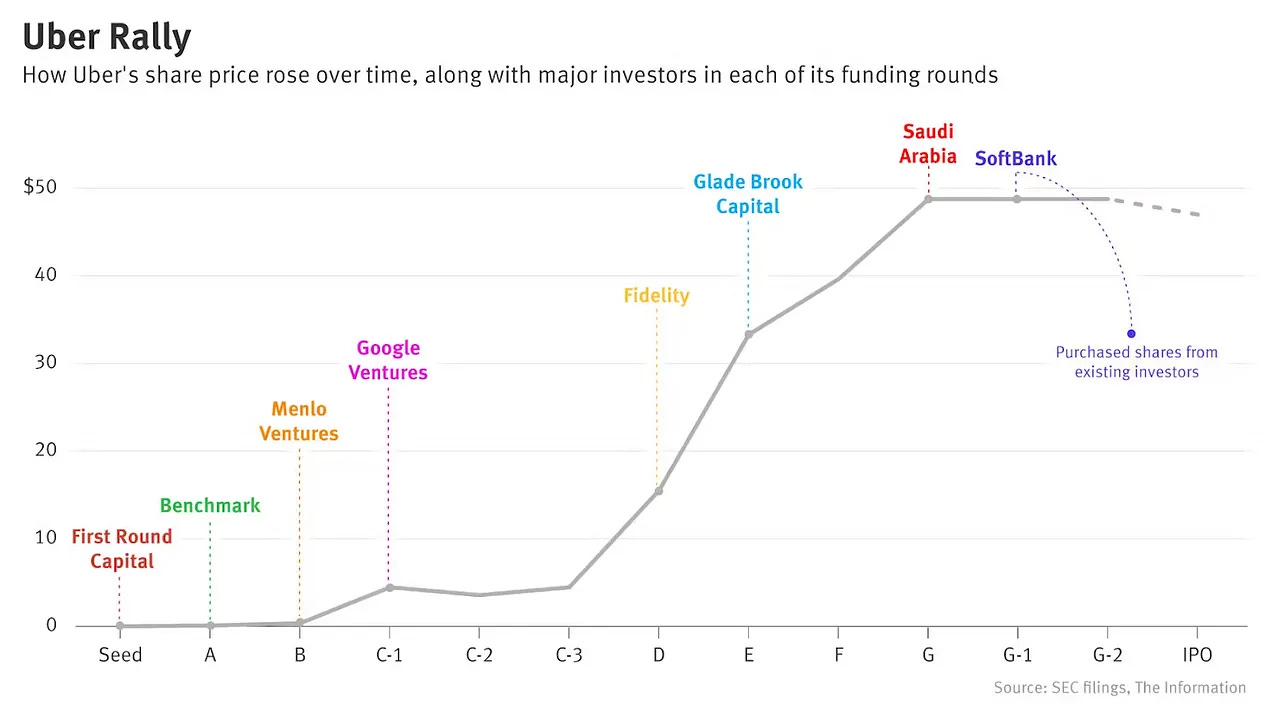

In 2010, First Round Capital led Uber’s seed round with a $510,000 investment. That early bet turned into one of the most celebrated wins in venture history, worth around $2.5 billion by the time Uber went public.

But here’s the twist. It could have been ten times bigger.

At the seed stage, First Round likely held a double-digit percentage of Uber. As the company raised round after round, bringing in billions from heavyweight firms, First Round’s stake kept getting diluted. They didn’t keep investing. Not because they didn’t believe in the company, but because they didn’t have the capital or fund structure to keep up. Their model was built for early-stage checks, not late-stage follow-ons.

Now compare that to Lowercase Capital, which also invested early but aggressively followed on, even buying secondaries. Chris Sacca’s firm ended up owning around 4% of Uber, enough to deliver a $1B+ return and make Lowercase one of the top-performing VC funds of all time.

3. The Math of Missing Out

Getting in early feels like a win. But without follow-on capital, that early win can get chipped away at quietly, round by round.

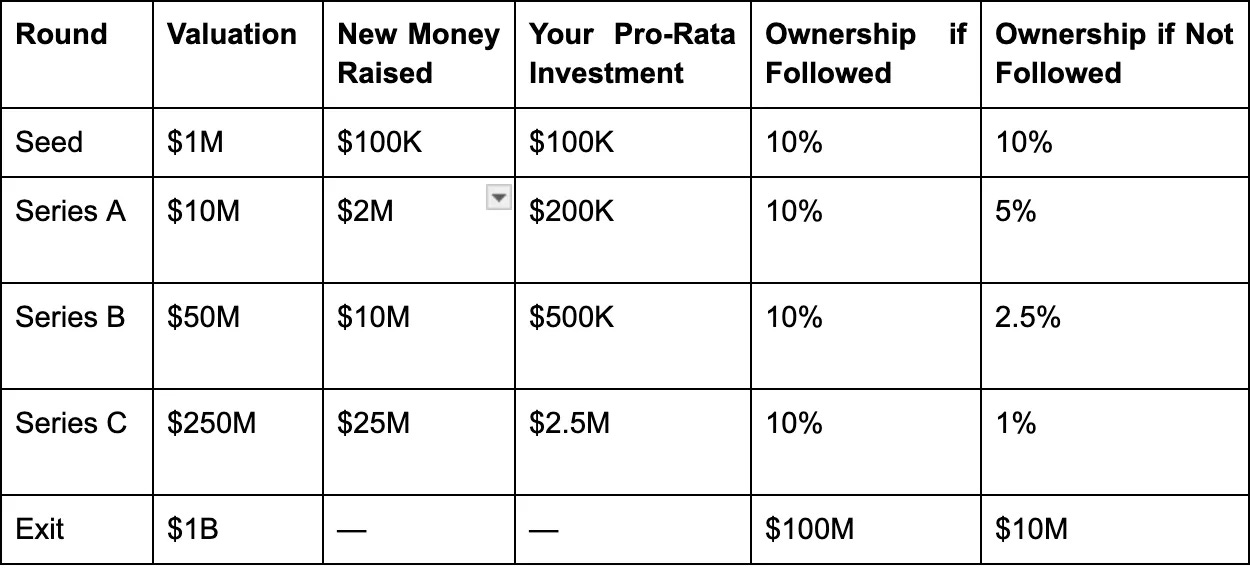

Here’s why: every time a startup raises money, it issues new shares. If you don’t participate in those rounds, your ownership shrinks (that’s dilution). Pro-rata rights are your option to fight it by buying enough new shares to keep your percentage steady.

Let’s say you put in $100K at Seed for 10% ownership. If the company grows fast and you don’t follow on, that 10% can drop to 2% by the time of exit. At a $1B exit, your return is $20M. Not bad, right? But if you’d kept your 10% by exercising pro-rata along the way, your return would have been $100M.

That’s an $80M difference, just from showing up with follow-on checks.

Here’s a simplified look at how that dilution plays out:

This is why so many early investors end up with paper gains that never reach their full potential. They get marked up, look great on paper, and then get crowded out as the company scales. The fund still wins, but it could’ve won a lot more.

Following on isn't cheap. But not following on is often far more expensive in the long run.

4. Why Early Funds Struggle to Follow Through

Spotting a breakout is hard enough. But for early-stage funds, staying in the game as that breakout scales is often a bigger challenge than it looks.

Let’s start with the basics - fund size vs. check size mismatch. A $20M seed fund writing $500K checks can’t realistically show up with $5M for a Series C. That kind of follow-on might wipe out a quarter of the entire fund. Even if the investor has pro-rata rights, actually using them means pulling capital from somewhere, and most small funds don’t have that kind of dry powder.

Then come the fund strategy constraints. Many early-stage firms are structured to avoid late-stage exposure. They’re built to find early opportunities, not underwrite later-stage growth at higher valuations and tighter return multiples. Some GPs may love the idea of following on, but if the fund’s thesis or LP agreement keeps them focused on Seed and Series A, they’re stuck. Investment theses need to be specific to be compelling.

There are also legal and timing issues. Pro-rata rights only matter if they’re clearly spelled out in the term sheet, and even then, they depend on timely execution. Founders need to give early investors a real chance to opt in, but in hot rounds, timelines shrink. Some investors miss the window or get pushed aside when bigger firms want more allocation. Without strong legal terms or clear communication, rights can quietly slip away.

Operational complexity is another hurdle. Following on consistently requires infrastructure such as:

Cap table tracking

Reserve management

Legal reviews

Investor coordination

Many small funds don’t have a full ops team or equity tracking tools. A missed email or delayed wire can mean losing out on a round, even when the intention was there.

And then there’s the psychology. Some investors hesitate to “pay up” at higher valuations, fearing they’ve already captured most of the upside. Others may get overly focused on diversifying their portfolio, choosing to fund new deals instead of concentrating on the ones that are already winning.

Put it all together, and you get the full picture. Early-stage funds often want to follow on, but they’re not always structurally or operationally equipped to do it. Capital limits, legal constraints, timing pressures, and internal strategy all combine to create friction. That’s how even the smartest funds fall into the pro-rata trap, not through lack of insight, but through lack of readiness.

5. The Ones That Got Away: Airbnb, Stripe, and the Cost of Hesitation

Uber wasn’t the only missed fortune. Two more giants - Airbnb and Stripe - exposed how quickly early ownership can slip through your fingers if you’re not ready to follow on.

Airbnb was founded in 2008, but by 2011–2013, it was still fighting uphill battles, such as regulatory chaos, legal pushback, and doubts about whether people would really rent out their homes to strangers. Some early investors sat on the sidelines during these years, watching from a distance instead of doubling down. The result was massive dilution just before the company hit its stride. By the time Airbnb went public at a nearly $100 billion valuation, only a few firms like Sequoia Capital, which stayed in through multiple rounds, held meaningful ownership.

Stripe was a different kind of challenge. The company moved fast. After its $2M seed round at a ~$20M valuation, Stripe rocketed to unicorn status in just a few years. Many early-stage investors simply couldn’t keep pace. Every round got bigger. Every valuation jump made pro-rata more expensive.

A $250K check at Seed might have required millions more to maintain pro-rata by the Series C. Most early funds didn’t have the reserves or flexibility. Even Elon Musk, who invested in the seed, later admitted he had no idea how big Stripe had become until much later.

These stories weren’t about missing the initial bet, they were about failing to keep up once the rocket took off.

6. How Newer Funds Are Adapting

The pro-rata trap has been a wake-up call. Early-stage investors now know that writing the first check isn’t enough, you need a plan to follow through. And many newer funds are building exactly that.

Reserving more capital upfront.

Instead of deploying 100% of a fund into first checks, many VCs now set aside 30–50% for follow-ons. That gives them the firepower to support their winners through at least a Series B, keeping their ownership from shrinking as rounds get bigger.

Launching opportunity funds.

Opportunity funds are separate pools of capital designed to follow on in breakout portfolio companies. These funds give GPs more flexibility, especially when their main fund is tied up or limited by early-stage mandates. Firms like Khosla Ventures, Canaan, and Y Combinator (via its former Continuity Fund) used this model to back their best companies without disrupting their early-stage strategy. YC’s fund, for instance, automatically exercises pro-rata rights in its top startups up to a set valuation threshold.

But it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution. Some firms are rethinking the model. Lux Capital recently decided to blend its early- and late-stage strategies into a single fund, citing a slowdown in late-stage activity and the inefficiencies of maintaining a separate vehicle. Others may follow suit as the funding landscape continues to evolve.

Building syndicates and SPVs.

There’s also been a rise in SPVs (Special Purpose Vehicles) and syndicates, especially among angels and micro-VCs. These lightweight investment structures let investors raise capital deal-by-deal, so if a breakout company raises a Series C, a small fund can still participate by rallying external backers into an SPV. Platforms like AngelList have made this easier than ever.

Adapting by design.

The bigger takeaway is that firms are adapting by design. Whether through larger reserves, dedicated growth vehicles, or flexible side vehicles like SPVs, today’s VCs are doing what it takes to avoid getting squeezed out of the upside they helped create.

7. Don’t Just Get In Early, Stay In

In venture, getting in early makes for a great story. But the biggest returns don’t go to the first check-in. They go to the investors who stick with the winners all the way through.

That’s what the pro-rata trap exposes. It’s not enough to back the next Uber, Airbnb, or Stripe. You need the capital, the structure, and the conviction to keep showing up in every round that matters. Because every round you sit out, you slowly lose your upside.

The best funds know this. They reserve aggressively. They launch opportunity vehicles. They get creative with SPVs. They plan for follow-ons before the term sheet is even signed.

Winning in venture isn’t just about finding the rocket ship. It’s about staying on board until it lands.

FAQ: The Pro-Rata Trap and Follow-On Investing in Venture Capital

What is the pro-rata trap in venture capital?

The pro-rata trap occurs when early-stage investors earn the right to maintain their ownership stake in future rounds (via pro-rata rights)—but fail to exercise those rights. This leads to ownership dilution, meaning their stake shrinks as the company raises more capital. While the initial investment may grow on paper, the investor misses out on the majority of upside by not doubling down on their winners.

What are pro-rata rights?

Pro-rata rights (also called "proportional rights" or "follow-on rights") are contractual clauses that give investors the option—but not the obligation—to maintain their percentage of ownership in future funding rounds. For example, if you own 5% of a startup after its Seed round, pro-rata rights allow you to invest more money in Series A and B to keep that 5% stake.

Why do investors miss pro-rata opportunities?

There are five main reasons:

Lack of capital – Smaller funds may not have reserves to follow on.

Fund strategy limitations – Some funds are designed only for early-stage exposure.

Operational friction – Tracking cap tables, round timelines, and wiring funds can be resource-intensive.

Legal or timeline constraints – Pro-rata rights might be vague, or hot rounds may move too fast.

Misjudged opportunity – Investors may underestimate the company’s upside or hesitate at higher valuations.

How does dilution affect early-stage venture returns?

Dilution occurs when a startup issues more shares during new funding rounds. If you don’t participate, your percentage of ownership decreases. For example:

A 10% seed stake could shrink to <2% by Series D if pro-rata is not exercised.

That means turning a potential $100M exit into a $20M return, leaving $80M on the table.

Can one missed pro-rata decision really cost millions?

Yes. In the case of Uber, some early investors who didn’t follow on lost out on billions in potential returns. Lowercase Capital aggressively exercised pro-rata and secondaries—earning over $1 billion on a small early stake. In contrast, other funds like First Round Capital saw their stake diluted because they didn’t have capital or mandate to keep investing.

How can early-stage VC funds avoid the pro-rata trap?

Reserve capital for follow-ons (often 30–50% of the fund).

Launch opportunity funds to back breakouts without disrupting early-stage focus.

Use SPVs (Special Purpose Vehicles) to syndicate follow-on investments with LPs or angels.

Leverage tools for cap table management and real-time alerts on portfolio rounds.

Define clear investment rights and expectations in the term sheet.

What is an opportunity fund?

An opportunity fund is a dedicated pool of capital used to reinvest in breakout companies from a VC's existing portfolio. These funds are often raised alongside or after a core fund, and they enable GPs to double or triple down on winners without violating LP mandates or over-concentrating the original fund.

What’s the difference between primary and follow-on investments?

A primary investment is when a VC invests in newly issued shares (e.g., Seed, Series A).

A follow-on investment is when a VC reinvests in the company during later rounds to maintain or increase ownership—often exercising pro-rata rights.

What are SPVs and how do they help with pro-rata rights?

An SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) is a single-purpose investment entity. If a fund doesn't have internal capital to exercise pro-rata rights, it can create an SPV to raise money from LPs or angels specifically to invest in one company. This enables smaller funds to retain ownership in rocketship companies without impacting their core fund reserves.

Which industries are most impacted by the pro-rata trap?

Industries with rapid growth, capital intensity, and winner-takes-most dynamics:

SaaS and software

AI and ML startups

Fintech and consumer tech

Marketplaces and e-commerce

Creator economy and B2C apps

In contrast, heavily regulated industries (e.g., healthcare, defense) may still favor deep specialization over speed, and the dilution risk from fast rounds is somewhat lower.

Is dilution always bad for early investors?

Not necessarily. If a company becomes wildly successful, even a diluted position can deliver strong returns. However, not following on in top companies caps your upside, while non-performing companies receive more attention. The best-performing VC funds concentrate capital in their highest-growth bets—those that escape the power law tail end.

How much capital should VCs reserve for pro-rata?

It depends on fund size and strategy, but top-performing early-stage VCs typically reserve 25–50% of their fund for follow-ons. Some even keep internal models to simulate dilution, ensuring they can maintain ownership up to a certain valuation cap (e.g., $500M or $1B).

Do angel investors have pro-rata rights too?

Yes—if negotiated. Angels in priced rounds or SAFE/convertible notes can ask for pro-rata rights, but these are less standardized than for institutional investors. Platforms like AngelList Syndicates and Rolling Funds have made it easier for angels to retain optionality in breakout deals.

How does the pro-rata trap impact LP returns?

Massively. The majority of a fund’s return often comes from 1–3 companies. If GPs fail to follow on in those outliers, the net fund return (TVPI, DPI, IRR) can drop significantly. LPs now ask more questions about reserve strategy, breakout support, and access to follow-on rounds before committing capital.

What are the signs a fund will avoid the pro-rata trap?

✅ Proactive reserve planning

✅ Track record of follow-ons in top performers

✅ Use of SPVs or opportunity funds

✅ Close founder relationships (helps with allocation)

✅ Legal protection and timing diligence in term sheets

✅ Clear GP incentives tied to concentrated upside

Which famous firms avoided the pro-rata trap?

Sequoia Capital – Maintains ownership across multiple rounds in companies like Airbnb, Stripe, and DoorDash.

Lowercase Capital – Doubled down on Uber, including secondary purchases.

Benchmark – Avoids large funds but actively supports follow-ons for outliers.

Which firms famously missed out by not following on?

First Round Capital – Made early bets in Uber but saw dilution as it scaled.

Smaller seed funds and angels – In many breakout cases (e.g., Stripe, OpenAI), early investors lacked follow-on power or missed round timing.

Why is this a growing issue in today’s VC landscape?

Because the speed of capital and size of rounds have accelerated dramatically. Startups now go from Seed to Series C in under 24 months. If a fund doesn’t have:

Real-time cap table insights,

Pre-planned reserves,

Access to later rounds…

…it risks watching its early stake vanish in the haze of mega-rounds.

Is the pro-rata trap fixable?

Yes—but only with intention. Funds need to design for it from Day 1:

Structure for follow-ons.

Build founder trust.

Use tools like AngelList, Carta, Pulley, or Allocate for tracking.

Maintain cash, clarity, and conviction when the breakout starts.

🧭 TL;DR — How to Avoid the Pro-Rata Trap

🟢 Reserve early

🟢 Exercise rights

🟢 Create SPVs when needed

🟢 Back your winners

🟢 Stay close to the founders

🟢 Don’t get greedy on valuation — get greedy on ownership

Great read, Ruben. It’s not just about getting in early, but about having the structure and reserves to stay in for the ride.

This works all fine if we retroactively pick the companies that went through the roof.

The picture isn't as rosy if we look at companies that barely made it.

And it's altogether different if you consider failures.

It matters whether the story told is about Airbnb, Foursquare, or Zume Pizza.

We are subject to survivorship bias. With another choice of examples, the story might have been on "How to Avoid Serious Losses Due to Sunk Cost Fallacy."