The Hidden Side of Venture Capital Funds Every Founder Should Know

A data-driven, founder-first guide to VC fund structure, fees, carry, reserves, and the new tools shaping how investors actually support you.

Why fund design matters more than the term sheet

You thought the investors that backed you in pre-seed would lead your Series A, but then you discovered their fund was already out of reserves. The term sheet never told you that, however, the fund design always could have.

When founders negotiate, most of the energy goes into the term sheet and the talks are all about valuation, board seats, protective provisions since those are all tangible and immediate.

But what actually dictates how a venture capital fund behaves once they’re on your cap table isn’t the “legalese” - it’s their fund design. That means how much capital they manage, how they reserve for follow-ons, what incentives their carry creates, and which fund-level tools they can (or can’t) deploy…

brought to yoy by Emergent:

From Google Intern to Google-Backed Founder 🔥

Mukund dreamed of Google in 2005. By 2009 he was inside, learning that real scale comes from real foundations.

That lesson became Emergent, the AI platform helping millions ship production-ready apps while others push prototypes…

2.5M builders. $25M ARR in five months. Now backed by Google’s AI Futures Fund.

Build your dream app today.

Use code GFF20 for 20 percent off

Fund design also determines the capacity and incentives for monitoring and value-add. Evidence from a Finland study found that private VCs were the most active in monitoring and governance, public VCs the least, and angels fell somewhere in between.

The takeaway is simple: structure drives behavior. If you understand the design of the fund, you can anticipate the kind of engagement you’ll actually get from regular board involvement to whether they’ll be there in the next round.

By the end of this article, you’ll know how to “read the fund” and you’ll be able to infer from first principles how likely a VC is to back you in the next round, how much time they’ll spend on your board, and what posture they’ll take when hard choices arrive.

Table of Contents

1. Quick Primer on How VC Funds Are Structured

2. Fees, Carry, and Waterfalls Explained For Founders

3. Fund Size Equals Strategy: What You Can Infer On Day 1

4. Reserves, Pro Rata, And Recycling: Will They Support You Later?

5. New Fund-Level Tools Founders Will Hear About: NAV Facilities And Continuation Funds

6. Portfolio Construction and Partner Bandwidth

7. Multi-Fund Platforms Vs Focused Funds: Conflicts and Guardrails

8. What “VC Value-Add” Actually Looks Like And How To Set The Cadence

9. A Founder’s Diligence Checklist To Read The Fund

10. How To Choose The Right VC For Your Stage And Plan

1. Quick Primer on How VC Funds Are Structured

At its core, a venture fund is a limited partnership. The general partner (GP) runs the fund by sourcing deals, making investments, and sitting on startup boards and the limited partners (LPs) provide the bulk of the capital and take a back seat in decision-making. LPs could be pension funds, endowments, family offices, or high net-worth individuals (HNWIs).

Each fund has a life cycle:

An investment period (usually the first 3–5 years) when new checks are written.

A longer fund term (often 10 years, with a couple of extensions) when the focus shifts from managing to exiting those investments.

GPs are paid in two ways: a management fee (commonly 2% per year on committed capital, tapering later) and carried interest (typically 20% of profits once LPs are repaid). These incentives explain why top VCs push for large outcomes. That’s because they don’t make real money from small wins.

Funds also come in vintages, each vintage is a separate vehicle raised in a specific year. Many firms run multiple funds at once (e.g. Fund IV investing new deals, Fund III managing older ones, plus a growth or opportunity fund on the side).

A key question for founders to ask is: which fund are you investing from, and how much capital is left in it? The answer tells you how much support they can realistically provide over time.

2. Fees, Carry, and Waterfalls Explained For Founders

Before diving into reserves and fund strategy, it’s worth understanding how VCs actually get paid. The mechanics of management fees and carried interest don’t just cover costs, they create the very incentives that drive fund behavior.

And the way those profits flow, through different waterfall structures, can change how patient or aggressive a VC is with your company.

Management fees and carry

Every VC fund runs on two revenue streams: management fees and carried interest. Fees are the steady paycheck. They typically range from 2% to 2.5% of committed capital each year in the early phase of a fund, tapering later.

Over the life of a ten-year fund, fees alone can add up to more than 15% of the total fund size. Carried interest, or “carry,” is the upside, which is usually set as 20% of the profits after LPs get their money back.

These mechanics explain a lot about investor behavior. Management fees keep the lights on, but carry is where wealth is made. That’s why VCs chase outlier outcomes rather than safe singles, as small exits rarely move their personal economics.

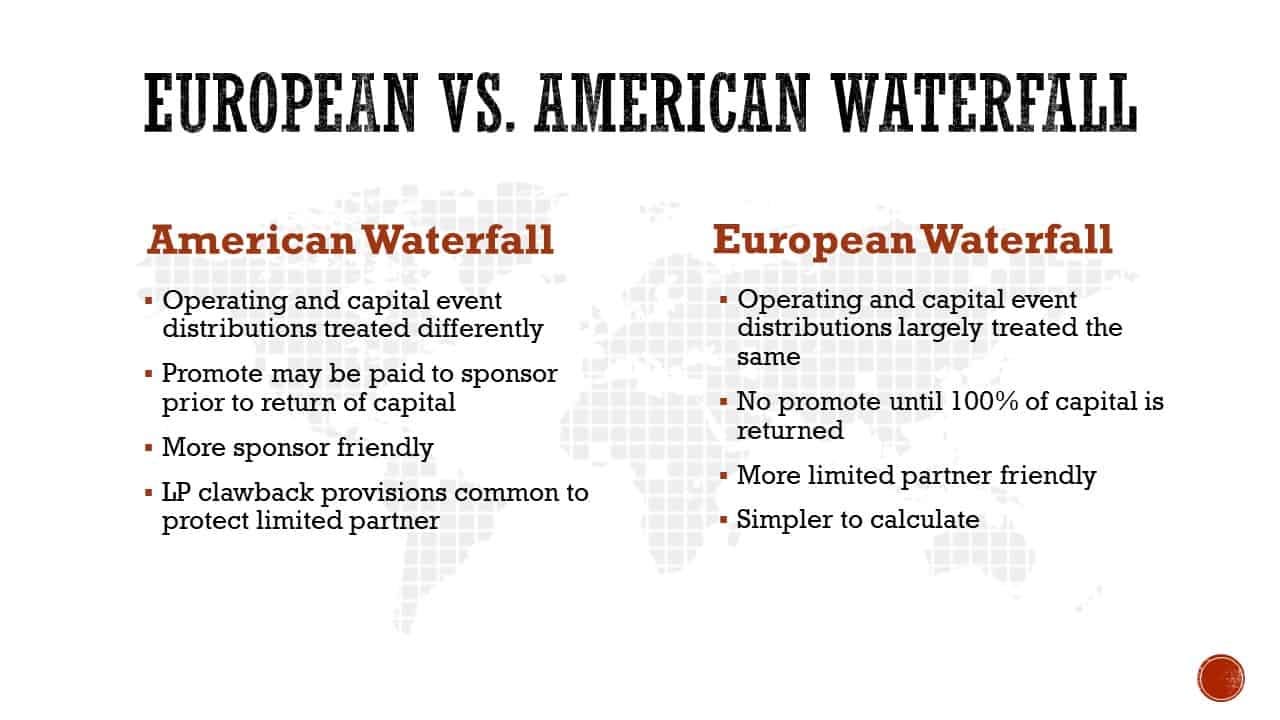

American vs. European waterfalls

How carry is paid depends on the waterfall structure. Under an American waterfall (deal-by-deal), GPs can take their 20% carry as soon as one investment returns cash, even if the rest of the portfolio is underperforming.

For example, if a $100M fund has one company that returns $50M early, the GP may already collect $10M in carry, even if the remaining investments later lose money.

A European waterfall (fund-as-a-whole) works differently. GPs only earn carry once the fund has fully returned its capital to LPs. In the same example, that early $50M payout would go back to LPs first, and GPs wouldn’t see carry until the fund overall crossed the $100M mark.

This structure generally promotes more discipline in follow-ons and patience with holding periods, since the GP’s economics depend on the whole portfolio’s success.

Carry and fees dictate how a fund sustains itself and how patient it can be with you. As a founder, it’s fair to ask which waterfall your prospective investor uses, whether there are hurdle rates or clawback provisions, and how their fees step down after the investment period.

The answers will tell you whether your VC has incentives aligned with patient, long-term support or is under pressure to notch quick wins.

3. Fund Size Equals Strategy: What You Can Infer On Day 1

Before you meet a partner or talk to an investor, the fund’s size already limits the game they can play.

That’s because fund size is what sets the check size, target ownership, portfolio breadth, and the outcomes that actually move the needle. Read that, and you can predict how they will show up for you from the first call.

Charles Hudson, a Veteran investor and Founder at Precursor Ventures says fund size is strategy. It dictates check size, ownership targets, and portfolio construction. The larger the fund, the larger the outcomes it must chase to matter.

How size shows up in founder-facing behavior

A small seed fund can win with smaller exits, so it can write smaller checks, move quickly, and often take earlier board risk.

A multi-hundred-million platform must deploy larger checks and concentrate ownership, so it will be choosier about stage and market and more focused on whether your outcome could “return the fund.” That phrase is literal: if a $100M fund owns about 20% and a company sells for $500M, the fund’s stake can repay the whole vehicle.

Portfolio construction links the two worlds. Funds decide how many companies to back, how much to reserve for follow-ons, and what ownership to target. Those levers are constrained by fund size, which is why a $25M seed fund behaves differently from a $750M multi-stage platform.

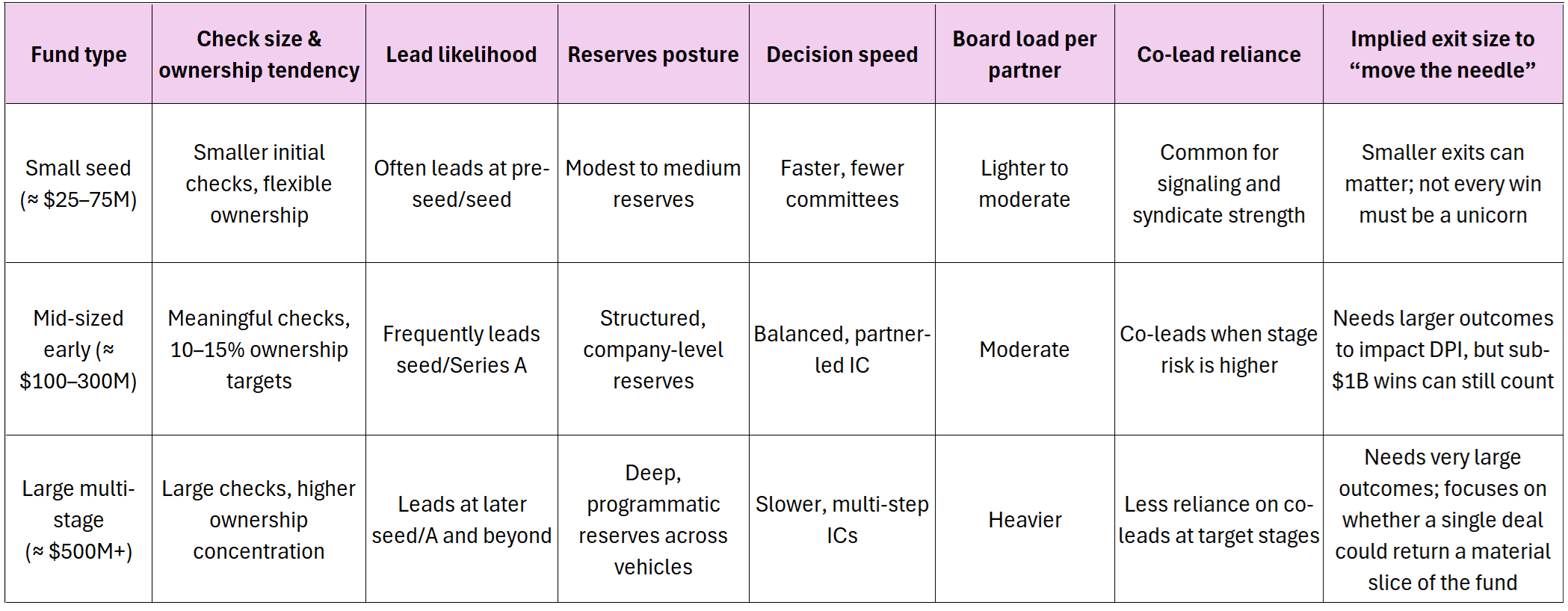

A quick map by fund size

(Illustrative tendencies. Calibrate to the specific firm you’re diligencing.)

Fund size is a shortcut to likely behavior.

Small funds can be quicker and more hands-on early. Large platforms bring deep reserves and brand, but will screen hard for markets and outcomes that can return a material share of the fund.

Use the first meeting to confirm the basics such as what check they plan to write, what ownership they need, whether they lead at your stage, how many boards your partner already carries, and how they model follow-ons. The answers should line up with the math of their vehicle.

4. Reserves, Pro Rata, And Recycling: Will They Support You Later?

A term sheet may give you rights on paper, but whether your VC actually shows up in later rounds depends on three fund-level levers: reserves, pro rata, and recycling. Each one determines how much dry powder your investor can deploy when you need them most.

Reserves

Most venture funds set aside a significant portion of their committed capital, which is often 40–60%, as reserves for follow-on investments.

This reserve policy is what allows a fund to double down on its winners, defend its ownership, or even lead a next round. A seed fund that reserves lightly may join your Series A pro rata but won’t have capacity to lead. A larger fund with structured reserves can anchor insider rounds and send a strong signal to the market.

Pro rata rights

Pro rata rights give investors the option to maintain their percentage ownership in future rounds, but they only matter if the fund has cash, mandate, and time left in the investment period.

An investor might promise support, but if the fund is out of capital, past its investment window, or restricted by mandate, those rights don’t translate into a check. Founders should confirm not just whether pro rata exists, but whether it’s realistically usable.

Sometimes, investors will want to eat the whole pie themselves.

Capital recycling

Another hidden tool is capital recycling, which is the ability of a fund to reinvest early proceeds from one exit back into new or follow-on deals.

Many LP agreements cap this at around 120% of committed capital, meaning a $100M fund might legally deploy $120M if early wins generate liquidity.

Recycling extends the effective size of a fund and gives GPs more flexibility to support portfolio companies, but it varies widely by vehicle. Recycling rights can make the difference between a fund that can keep backing you and one that quietly runs out of steam.

Reserve math is one of the clearest signals of how a VC will behave post-seed. Ask directly during the due diligence process. Here are five questions that can tell you what you need to know:

What percentage of your fund is reserved for follow-ons?

How much of those reserves are discretionary versus earmarked by policy?

How long does your investment period run, and does it cover my likely next round?

Do you have recycling rights in your LPA, and how do you use them?

Can you lead insider rounds, or only participate pro rata?

5. New Fund-Level Tools Founders Will Hear About: NAV Facilities And Continuation Funds

The venture toolkit has been evolving in recent years.

Beyond reserves and recycling, funds are now deploying more complex instruments to extend runway, manage liquidity, and keep backing portfolio companies. Two of the most important are NAV facilities and continuation funds.

Founders don’t need to become fund finance experts, but knowing these tools exist, and what they imply, certainly helps them ask sharper questions when diligence turns serious.

NAV facilities

A NAV facility is a loan taken out by the fund itself, secured by the net asset value (NAV) of its portfolio. Funds use these credit lines to support follow-on investments or to smooth distributions back to LPs.

On the surface, this creates flexibility for VCs with limited dry powder, allowing them to still write checks. But it also introduces leverage and opacity at the fund level, which is why LPs often scrutinize their use.

Collateral in these facilities can range from specific portfolio company shares to the entire fund’s net asset value, and investors often raise concerns about the added leverage, potential risk layering, and lack of transparency.

Founder diligence questions:

Does your fund use NAV facilities, and if so, under what limits?

How do you decide between deploying reserves versus drawing on credit?

Are there covenants or triggers that could affect support for portfolio companies?

GP-led secondaries and continuation funds

A continuation fund is created when GPs move specific assets from an older fund into a new vehicle, often bringing in fresh LP capital to extend the holding period.

This can feel like stability for founders, meaning their investor now has new dry powder earmarked for their company. But it can also change incentives as carry resets in the new vehicle, which may change how aggressively your VC pushes for exit timing or governance changes.

Continuation funds are often described as a way to align fresh capital with promising companies, but they also raise potential conflicts that need to be managed carefully around valuation and governance.

Founder diligence questions:

Has my company been moved into a continuation fund, and if so, why?

What governance or board terms change under the new structure?

How do you manage conflicts of interest between LPs in the old fund and new investors?

NAV facilities and continuation funds are not inherently good or bad. They’re tools that can extend your investor’s capacity to support you, but they also layer on new incentives and risks. When you hear these terms, don’t tune them out. Ask clear questions to understand how they affect your VC’s ability and motivation to back you in the next phase.

6. Portfolio Construction and Partner Bandwidth

Behind every fund is a spreadsheet that secretly dictates how much attention you’ll actually get, that is the portfolio construction model.

How many companies a fund backs, how fast it deploys capital, and what ownership targets it sets all add up to a practical question: how much time will your partner spend on your business?

How portfolio design affects attention

A fund investing in 40 companies across two stages will inevitably stretch partner bandwidth thinner than one investing in 15 highly concentrated bets.

Ownership targets matter too. For example, if a firm is aiming for 15–20% stakes, it may reserve more board seats and dedicate more resources than a fund that accepts 5% slices across dozens of names.

Pacing also plays a role. When a fund is deploying aggressively, partners are constantly in deal mode, which can dilute the time available for active portfolio support.

The board seat constraint

The clearest bottleneck is board load. Partners can only take on so many active boards before effectiveness drops. That number varies, but once a partner is juggling more than eight or ten companies, depth of engagement suffers.

Founders often focus on the brand of the firm, but it’s the human bandwidth of the individual partner that determines whether you get strategic time, introductions, and problem-solving when it counts.

The throughline is simple: structure drives behavior, and partner capacity is the limiting factor.

So here’s an expert tip. When you diligence a fund, don’t just ask about reserves and check size. Ask about partner load and board cadence.

How many boards does your partner sit on today? How often do they meet with portfolio founders? Who else in the firm supports those relationships?

The answers reveal far more about your likely support than any “value-add” slide in a pitch deck.

7. Multi-Fund Platforms Vs Focused Funds: Conflicts and Guardrails

As venture firms scale, many now operate multiple vehicles under the same brand: a seed fund, a growth fund, maybe an opportunity fund alongside. On paper, this gives them the flexibility to support you from seed to IPO. In practice, it also creates conflicts of interest when different vehicles want exposure to the same round.

How conflicts can show up

The classic case is a growth vehicle bidding for your Series B while the seed fund that first backed you wants to keep its pro rata. So who sets the price? Which investment committee has the final say?

Without clear rules, founders can find themselves caught between two arms of the same firm negotiating against each other.

Guardrails that matter

To manage these situations, firms typically put in place guardrails. Pricing may be benchmarked by independent market terms or third-party validation. Investment committees for different vehicles may operate separately to avoid self-dealing. Some LP agreements also include opt-out provisions, allowing funds to pass on conflicted deals without penalty.

The exact mechanisms vary, but the principle is the same: conflicts exist, and they need managing.

For founders, the point isn’t to avoid multi-fund platforms because they bring deep capital and credibility. The point is to understand how they handle conflicts before you’re in the middle of a priced round. In diligence, ask questions like:

How do you manage pricing when two of your vehicles want to invest in the same round?

Do separate investment committees decide for each fund?

Are there opt-out provisions or policies if conflicts arise?

How have you handled cross-fund conflicts in the past?

Clear answers signal whether the platform has thought through these scenarios, or whether you might be the test case.

8. What “VC Value-Add” Actually Looks Like And How To Set The Cadence

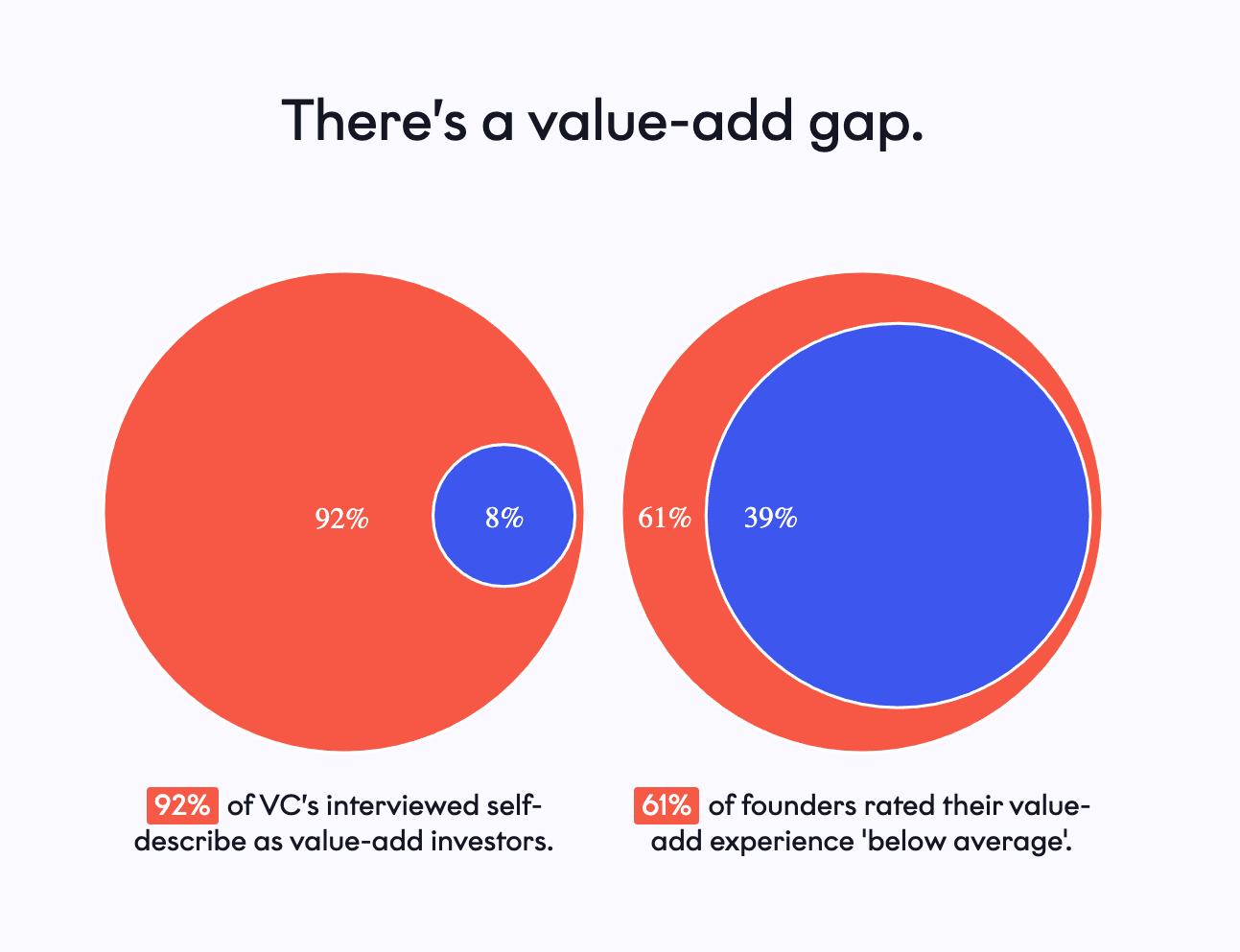

Every investor promises “value-add,” but the data shows which forms of support actually move the needle.

Studies consistently find that active monitoring and governance correlate with better innovation and stronger exit outcomes.

Companies backed by engaged VCs professionalize faster, hiring CFOs, upgrading boards, and installing key executives earlier than their peers.

Value-add, in practice, is less about flashy introductions and more about disciplined oversight.

Our Finland research sharpened this picture. Private VCs, with tighter portfolios and direct carry incentives, were the most active in monitoring performance and driving governance. Public VCs, by contrast, carried more companies per manager and were often forced to delegate oversight to external board members, limiting hands-on engagement. Angels spanned the spectrum, from deeply involved mentors to passive check-writers.

The clear takeaway is that the structure of the capital provider, not just their personal promise, predicts how involved they’ll be post-investment.

A founder’s operating model

Rather than waiting to see how a VC interprets “value-add,” founders can set the cadence themselves. A simple, repeatable model works best:

Monthly KPI pack to align on metrics and early signals.

Quarterly strategy deep-dive to step back from the day-to-day and address positioning, product, or fundraising runway.

Pre-agreed talent search triggers for when a VP-level or C-suite hire becomes critical.

This approach creates clarity, keeps investors productively engaged, and prevents “value-add” from drifting into sporadic, ad hoc conversations.

The best VCs aren’t those who claim they’ll open every door; they’re the ones who commit to a structured rhythm of support.

In diligence, ask how a partner prefers to engage, and propose your cadence. A VC willing to align on discipline upfront is far likelier to deliver meaningful help when it counts.

9. A Founder’s Diligence Checklist To Read The Fund

Founders often spend more time dissecting term sheets than asking about the engine that drives investor behavior, which is the fund itself.

A few sharp questions can reveal how much support you’ll actually get, how decisions are made, and whether the economics align with your company’s path. Use this checklist as a ready-to-go script in diligence.

What is the size and vintage of your current fund?

How much of the fund has already been called and deployed?

When does your investment period end?

Which carry waterfall do you use - deal-by-deal or fund-as-a-whole?

What percentage of the fund is reserved for follow-ons?

How do you approach pro rata rights - policy versus practice?

Do you have capital recycling rights, and if so, how do you use them?

Does your fund employ NAV facilities, and under what conditions?

What is your continuation fund policy if portfolio companies need extended support?

How many active boards does my partner currently sit on?

How are investment decisions made - partner-led, IC vote, or other process?

This isn’t about tripping up an investor, but about seeing the whole picture. If a fund can’t answer these questions clearly, that silence is an answer in itself.

10. How To Choose The Right VC For Your Stage And Plan

The real skill in fundraising isn’t spotting the biggest brand, it’s matching your company’s trajectory with the fund economics behind the logo.

Your capital plan and likely exit path should align with a VC’s size, reserves, and toolset.

A $25M seed vehicle may be a great partner for an early product-market fit journey, but it won’t have the depth to lead multiple insider rounds.

A $750M multi-stage platform can provide long-term support, but it will screen harder for markets where billion-dollar exits are possible.

The right fit is the one whose design matches your path.

Three rules of thumb

First, if you expect to raise multiple rounds before profitability, prioritize funds with explicit reserve policies and recycling rights; they’re best positioned to keep supporting you through A and B.

Second, if your likely exit path is sub-$500M, align with smaller or mid-sized funds where those outcomes can still “return the fund” and generate real carry for partners.

Third, if your company may need patient capital over a long horizon, ask about investment period, continuation vehicles, and NAV usage to see whether the fund can truly stay the course.

You don’t have to master fund mechanics to make sharper choices, you just need to connect your plan to the incentives baked into your investor’s vehicle.

When you pick a VC whose structure lines up with your stage and strategy, you gain more than capital: you gain a partner with the built-in ability and motivation to see your journey through.

The power is in your hands to choose alignment over brand.

Fantastic content. Thank you for putting together such a comprehensive guide