How to Evaluate a Startup’s Exit Potential: Signs, Metrics, and Red Flags

Learn how investors assess a startup’s exit path. From M&A readiness and IPO fit to founder alignment, cap table health, and sector timing.

Every investment ends one way or another. For venture investors, the question isn’t if a startup will exit. It’s how, when, and at what multiple.

In today’s tighter markets, where IPOs are rare and acquirers are selective, assessing exit potential early has become an important investment discipline.

The goal is to understand the mechanics that make a startup exit-ready and spot the red flags before they stall the deal. The sooner you start asking the right questions, the better your chances of backing a company that exits well, and returns capital when it counts.

Brought to you by Vanta🚀. Founder to Founder: Build a Breakout Startup in the AI Age

Join Vanta’s Christina Cacioppo and The Generalist’s Mario Gabriele on June 26th for a live chat on how AI is reshaping the startup playbook, and what founders need to do to stand out.

✅ Use AI to accelerate early traction

✅ Find product-market fit faster

✅ Scale smarter with the right tools

Learn actionable strategies to thrive in the AI age—even without brand recognition or deep funding.

Table of Contents

Why Exit Strategies Matter More Than Ever

The Anatomy of a Viable Exit: What Investors Should Look For

Founder Intent and Incentives: Alignment or Risk?

Are Exits Happening in This Sector?

Strategic Acquirers: Mapping the Exit Landscape Early

Financial Trajectory and Unit Economics: Are They Built for an Exit?

Avoiding Red Flags With Cap Tables and Exit Waterfalls

Assessing the Startup’s Narrative as a Strategic Asset

Smart Capital Starts with a Clear Path Out

1. Why Exit Strategies Matter More Than Ever

Exit thinking isn’t something you tack on in a Series C board meeting. It needs to show up early; sometimes even before the first check hits the bank. Because in this market, the path to liquidity is narrower, slower, and far less predictable than it used to be.

Over the past two years, capital has tightened. The IPO window has barely cracked open, and M&A appetite is more selective. At the same time, LPs are watching timelines closely. They want to know when and how a company will exit and what that means for fund returns. That pressure travels upstream fast.

A decade ago, you could assume an ambitious founder would ride into a growth round, go public, and everyone would win. Today, that playbook has more caveats than guarantees. Some companies will get acquired. Others may lean into secondary sales. A few will quietly fade out. The shape of an exit matters, but so does its feasibility.

That’s why evaluating exit potential isn’t a binary call between IPO and acquisition. It’s a broader lens. What are the structural signals? Is there precedent in the sector? Would a strategic or financial acquirer pay a premium? What does the cap table look like under pressure?

You don’t need to force an exit strategy on day one, but you do need to back companies that can keep their options open. Because when the market gets choosy, optionality isn’t just helpful. It’s survival.

2. The Anatomy of a Viable Exit: What Investors Should Look For

Not every exit is created equal, and not every startup is built to get there.

As investors, the question isn’t just what’s the likely exit route?, but is the business truly positioned to take it? That means looking at timing, structure, and fit.

A Look at the Landscape: IPO, M&A, Secondaries, and the Rest

There are only so many ways out. The traditional options - IPOs, acquisitions, secondary sales - are still in play, but their viability shifts with market cycles.

IPOs are aspirational, but rare. The public markets have been tight, and only the cleanest, most mature businesses are getting through the gate. Most others are being told to wait.

M&A continues to dominate. It’s where the vast majority of startup exits happen, especially below the $200 million mark. But strategic and financial buyers are more selective now. They want clear synergies, strong retention, and real margins.

Secondary sales are an increasingly important path to partial liquidity, especially for growth-stage companies. But these require clean governance and a compelling story. If a buyer senses messiness, on the cap table or in the numbers, they’ll likely walk.

And then there’s SPACs. They’re still technically on the table, but the market’s cooled. For capital-intensive or difficult-to-price businesses, they might still be viable. For most startups, they aren’t the answer anymore.

In short, the right exit route depends on timing and market mood. What worked two years ago might be off the table today.

Matching the Exit Path to the Business

Exit viability is no more about external conditions. These days, it's more about whether the company itself fits the kind of deal that’s possible.

Early-stage companies, especially those building deep tech, tend to exit through acqui-hires or early strategic sales. These are rarely headline-grabbing deals, but they can return capital when structured well.

Later-stage startups with product-market fit, scale, and a reliable revenue base may be in a stronger position to run a formal M&A process or prep for a public listing, if the markets are open.

Sector matters too. SaaS, fintech, and healthtech tend to have established buyer ecosystems. Acquirers know how to evaluate them and are often actively looking. In newer or harder-to-categorize sectors like climate tech, mobility, or frontier hardware, exits often come later, through roll-ups or secondaries. That longer timeline needs to be priced into your thinking from day one.

Structure plays a quiet but decisive role. A startup can have solid fundamentals and still struggle to exit if it’s carrying the weight of multiple liquidation preferences, a crowded cap table, or an inflated last-round valuation. These things don’t just affect payout, they can scare off buyers altogether.

3. Founder Intent and Incentives: Alignment or Risk?

A startup’s ability to exit doesn’t just depend on the market. It depends on the mindset of the person driving the wheel.

Founders often talk about building long-term, lasting companies, and rightly so. But behind that ambition, their personal goals vary more than you might think. Some are chasing unicorn status. Others would happily take a strategic acquisition at $100 million and move on. Neither approach is wrong. What matters is whether you, as an investor, know which version you’re backing.

Misalignment around exit expectations is one of the most common and most preventable sources of friction between founders and investors. If a founder is fixated on going public someday, but your fund is built for a quicker M&A timeline, that tension will surface eventually.

The same applies if the founder sees dilution as something to avoid at all costs, while you’re anticipating follow-on rounds that require aggressive capital deployment.

A founder’s past can be telling here, but so can their answers to a few direct questions:

Are they aiming to build a unicorn, or would a $100M acquisition be a win?

Have they exited before, or is this their first run?

Do they understand dilution, control, and how preferences shape outcomes?

Are they willing to talk about exits openly, even if they’re years away?

These are questions worth asking early. Because it’s much easier to align when things are calm than to renegotiate expectations when the exit clock is ticking.

Strong founder-investor alignment doesn’t mean agreeing on every number. It means having honest conversations about outcomes, trade-offs, and timelines before they become a source of regret. A founder doesn’t need to have the perfect answer on day one, but they do need to be self-aware, open to feedback, and willing to revisit the plan as the business evolves.

According to the Harvard Business Review, build rapport with founders early on, embrace their idiosyncrasies, and frame initiatives as experiments to ease their concerns about change.

At the end of the day, the best exits are the ones where everyone is pulling in the same direction. The worst are the ones where you realize too late that you weren’t even on the same map.

4. Are Exits Happening in This Sector?

Exit potential isn’t just a company-level question. It’s a sector-level pattern.

Some industries have clear exit momentum - regular acquisitions, consistent IPOs, predictable multiples. Others are tougher. There’s nothing wrong with backing a bold bet in a slower-moving category, but investors need to price that reality in early. Because if the market isn’t buying companies like this one, you need to ask why you think this time will be different.

Sector trends shape everything - buyer appetite, exit multiples, and timing. Sectors like fintech, SaaS, healthtech, and e-commerce continue to see the most deal flow.

They attract both strategic and financial acquirers, and they tend to generate exits at every stage, from sub-$50M acquihires to public listings. In contrast, sectors like edtech, mobility, or clean energy often see longer holding periods and more sporadic M&A. The exit paths exist, but they’re narrower, slower, and often tied to policy cycles or infrastructure developments.

This doesn’t mean you avoid underdeveloped categories. It just means you go in with your eyes open. If you're investing in climate tech, for example, you may be underwriting for a 10-year outcome. That might still work for your fund, but only if the rest of your portfolio isn't tied up in similar long bets.

The best way to ground your assumptions is to study comparables. Tools like PitchBook, CB Insights, and Crunchbase make this easier than ever. You can screen for startups in the same category, filter by funding stage or geography, and look at who acquired them, or if they exited at all. It’s a fast way to see if the market is rewarding similar businesses, and what it took for them to get there.

If the only exits in a space are distressed fire sales or one-off outliers, that’s not a pattern. It’s a caution sign. On the other hand, if you're seeing consistent transactions across Series B, C, and late-stage, there’s a roadmap forming. That roadmap helps you evaluate not only if a company can exit, but also how it stacks up against others who have already done so.

The key is not to bet in a vacuum. Historical exit data won’t tell you the future, but it will tell you what kind of past the future is likely to rhyme with.

5. Strategic Acquirers: Mapping the Exit Landscape Early

Strong exits don’t usually happen by accident. More often than not, they’re the result of early planning, long-term relationship-building, and a clear understanding of who’s likely to care when the time is right.

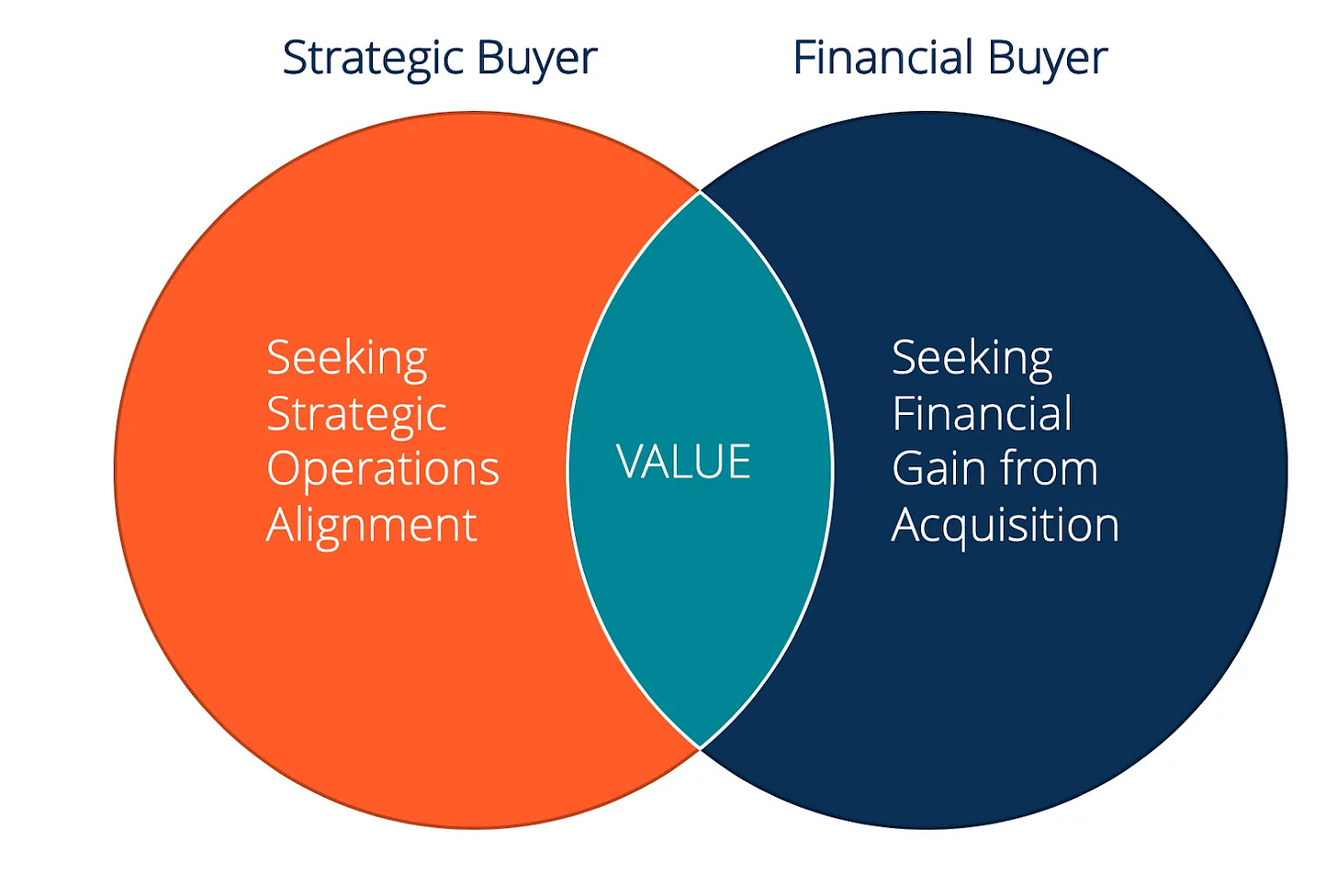

Strategic acquirers operate on different timelines and with different incentives than financial buyers, and if you know how to read the signs, you can start positioning a company years before the first term sheet ever lands.

Strategic Acquirers Think in Synergies

Unlike financial acquirers who buy for returns, strategic buyers are looking for fit. They care about how your startup amplifies their existing business, whether that’s unlocking new distribution, accelerating product development, filling a competitive gap, or eliminating a threat.

Some of the best exits start as partnerships. A product integration. A co-marketing initiative. A joint pitch to a shared enterprise customer. When a company starts working its way into another’s workflows or customer base, it becomes part of their future. And when acquisition conversations begin, they’re not starting cold.

Reverse-Engineer the Landscape

Investors can map the M&A terrain early by looking at who’s buying and why. Study the acquisition histories of larger players in the space. What types of companies do they target? At what stage? How often? Are they acquiring for tech, talent, or traction?

Beyond formal M&A, watch for patterns in partnerships. Which companies are co-selling? Who’s launching integrations or shared features? These moves often precede acquisition interest. And don’t overlook adjacent players - roll-up strategies from neighboring sectors can surface new acquirers that weren’t obvious when the company was founded.

This kind of reverse-engineering helps you shape more than just the exit narrative. It can influence product decisions, fundraising milestones, and go-to-market strategies. If you know what acquirers value, you can make sure the company is measuring and building the right things.

A good business is one thing. A good business built in full view of the right buyer? That’s when the exit gets interesting.

6. Financial Trajectory and Unit Economics: Are They Built for an Exit?

A flashy growth curve might grab headlines, but exits don’t close on momentum alone. Buyers, whether public market investors or strategic acquirers, want to know if the business under the hood actually works.

That means more than top line numbers. It means scalable, sustainable unit economics that tell a coherent story from revenue to retention to return on capital.

When a startup is built for an exit, you can see it in the numbers long before you see it in the pitch deck.

Growth with Quality, Not Just Speed

Yes, growth still matters. But buyers are far more focused now on how a company is growing. High churn, bloated customer acquisition costs, or a lack of repeatable sales motion can all turn a promising revenue line into a red flag.

Strong businesses show signs of compounding value - recurring revenue, high customer retention, and expanding contracts over time. Metrics like net dollar retention (NDR) and gross revenue retention (GRR) often speak louder than year-over-year growth. If customers stick around and spend more, that’s real leverage.

Gross Margins and Unit Economics That Scale

Margins tell you how much of that revenue counts. For most software companies, gross margins in the 70–90% range are the norm, and anything significantly lower can signal operational inefficiencies or infrastructure drag. For product-led companies or marketplaces, margin structure might be lower, but it still needs to show consistency and a path to improvement.

Unit economics are the heartbeat of business viability. A strong LTV:CAC ratio (typically 3:1 or better) shows that customers are worth more than it costs to acquire them.

A short CAC payback period, ideally under 12 months, signals efficiency. These metrics tell a buyer whether growth is profitable or subsidized by aggressive spending.

Burn Multiple and Capital Efficiency

In markets where capital isn’t cheap or abundant, burn multiple has become a go-to lens for evaluating startups. It answers a simple question: how much are you burning to generate each incremental dollar of ARR?

A burn multiple around 1.5 is considered strong, especially in enterprise SaaS. If you’re burning $5 million to add $2 million in ARR, the burn multiple is 2.5—not great. That doesn’t mean the company’s doomed, but it suggests the growth story needs scrutiny.

Buyers want to see that capital raised has been put to productive use. That’s where capital efficiency metrics - like revenue per dollar raised or ARR-to-capital ratio - can help frame the company’s ability to scale without constant top-ups.

Profitability on the Horizon

An exit doesn’t require the company to be profitable, but it does require the company to look like it could be. Buyers don’t want open-ended losses. They want a clear path to break-even or margin expansion, especially if the acquisition is intended to fold into an existing business line.

Knowing your numbers means that you are doing more than impressing a board; it means that you understand how to navigate, negotiate, and act when opportunity shows up.

Companies that have their financial house in order (clean metrics, solid forecasting, smart spend) earn trust. And that trust translates into higher exit valuations and faster deal velocity.

A business built for exit doesn’t just grow. It grows with discipline. When the financials align with the story, buyers don’t have to squint to see the value. They just have to decide how much they’re willing to pay.

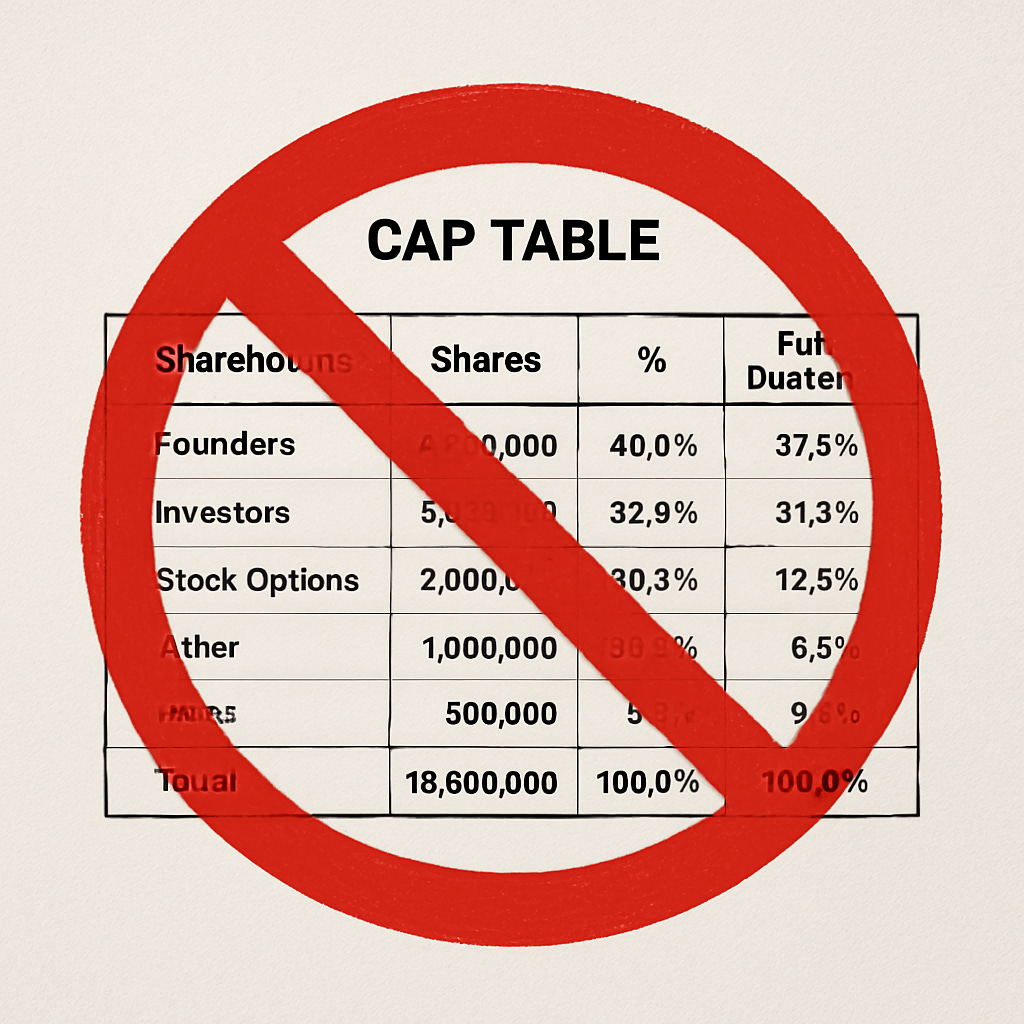

7. Avoiding Red Flags With Cap Tables and Exit Waterfalls

A startup might have a great product, strong growth, and even a willing acquirer. However, if the cap table is a mess, the deal can fall apart fast. Exit outcomes aren’t just about what the company sells for. They’re about who gets what, and whether that distribution actually makes sense to the people involved.

You can’t evaluate exit potential without understanding the structure behind the ownership.

When the Cap Table Becomes the Problem

Cap tables don’t need to be perfect, but they do need to be clean. When ownership is overly fragmented or when preference stacks get out of hand, it becomes harder to close a deal because someone always feels shortchanged.

The biggest red flags? Stacked SAFEs that convert in unpredictable ways. Multiple rounds of preferred shares with escalating liquidation preferences. Tiny slivers of ownership across a dozen small early investors. And perhaps most overlooked - an inadequate or nonexistent ESOP. If the team doesn’t have meaningful equity, retention post-acquisition becomes a problem. No buyer wants to inherit an unmotivated crew.

Even seemingly minor details can create headaches. If investor consents are unclear or if supermajority provisions are scattered across documents, coordinating an exit turns into a legal and logistical maze. Smart investors look for simplicity - clear ownership, clean preferences, and predictable governance.

Exit Waterfalls: Where the Math Gets Real

An exit waterfall shows exactly how proceeds from a sale flow through the cap table. It reveals whether that $200 million exit is a windfall or a disappointment, depending on who holds what, and under what terms.

Add a few 2x liquidation preferences on top of a heavily diluted common pool, and you might find that the founders and team walk away with very little, even in what looks like a strong exit. Worse, if early investors are underwater or later-stage money dominates the payout, misaligned incentives can kill the deal altogether.

That’s why running such simulations early matters. Before an acquisition offer ever shows up, you’ll want to know, does this structure reward the people who made the company what it is? Or does it lock them out of the upside? If it’s the latter, no amount of growth is going to fix it in time.

The best investors don’t just look at valuation. They look at the distribution. Because in venture, outcomes are rarely about what’s announced, they’re about what lands in the bank.

8. Assessing the Startup’s Narrative as a Strategic Asset

When it comes to exits, the numbers tell part of the story. The narrative fills in the rest.

Strategic acquirers and public market investors often make decisions based on how well a company fits into a broader picture. A startup with a clear story is easier to evaluate, easier to sell internally, and easier to back with conviction. Without that, even strong businesses can get overlooked.

It starts with clarity. Is the company solving a real, persistent problem? Or is it just a useful feature that might fade with time? Acquirers tend to pay a premium for companies that address high-stakes issues. Painkillers move faster than vitamins.

Next, consider whether the company is part of something bigger. Does it align with a shift the industry is already chasing? That could be a wave of AI adoption, a new regulatory framework, or a change in consumer behavior. When a startup becomes a gateway to relevance, larger players tend to notice.

Narrative also influences how a company is positioned. A startup that knows whether it is a product, a platform, or an ecosystem often stands out more clearly than one trying to be all three. Clarity of message allows buyers to see where it fits and how it grows. That creates confidence.

None of this means a founder needs to craft an artificial pitch. The best narratives are grounded in truth. But they are told with intention. They show why the company matters now, and why it will keep mattering three years from now.

9. Smart Capital Starts with a Clear Path Out

Exit potential isn’t something to figure out later. It belongs at the start, right alongside market size, team, and product. When you understand how a company might exit, you make better calls about when to invest, how much risk to underwrite, and what milestones matter.

That doesn’t mean forcing an outcome. It means recognizing which businesses are positioned to create real, liquid value and which ones might struggle when the time comes.

In this market, liquidity is a strategy, not a surprise. The best investors don’t wait for the exit conversation. They’re already looking for the signals.

FAQ: Evaluating a Startup's Exit Strategy and Potential

What is a startup exit strategy?

A startup exit strategy is a plan for how founders and investors will eventually realize returns on their investment. Common exit routes include an IPO (Initial Public Offering), acquisition (M&A), or secondary share sales. A well-defined exit strategy helps investors understand the timeline and pathway to liquidity.

Why is evaluating exit potential important in venture investing?

Because every venture investment must eventually convert into cash or stock in a liquid entity. In today’s tighter capital markets—where IPOs are rare and acquirers are more selective—exit potential helps investors:

▫️ Identify high-return opportunities

▫️ Avoid cap table and governance issues

▫️ Align with founder incentives

▫️ Understand realistic timelines and market fit

What are the most common startup exit paths?

▫️ Acquisition (M&A): The most frequent path, especially for sub-$200M outcomes

▫️ Initial Public Offering (IPO): Rare, reserved for high-scale, clean, profitable companies

▫️ Secondary Sales: Partial exits via share transfers, often during late-stage rounds

▫️ Acquihires: Talent-focused acquisitions, usually at lower valuations

▫️ SPACs: Fewer than before, but still used in select capital-intensive sectors

What makes a startup “exit-ready”?

Exit-ready startups usually have:

▫️ Clear product-market fit

▫️ Clean cap table with manageable preferences

▫️ Strong financials (high retention, gross margins, LTV/CAC)

▫️ A scalable narrative aligned with market trends

▫️ Identified strategic acquirers or buyer signals

▫️ Founders open to exit discussions and aligned incentives

How do founder incentives affect exit outcomes?

Founder misalignment is a silent deal killer. If a founder wants to build a $10B company but investors expect a $200M strategic exit, friction is inevitable. Evaluating intent early ensures everyone is working toward the same goal. Ask:

▫️ What does success look like to you?

▫️ Are you open to M&A, or IPO-only?

▫️ Have you exited before, or is this your first venture?

What red flags on the cap table can block an exit?

▫️ Multiple stacked SAFEs with unclear conversion

▫️ Overly complex liquidation preferences

▫️ Tiny equity slices for early investors or team

▫️ Missing ESOP or under-motivated employees

▫️ Supermajority or veto provisions that stall consensus

A chaotic cap table leads to delayed deals—or no deal at all.

How do acquirers assess startup viability?

Strategic acquirers look for:

▫️ Product synergies

▫️ Distribution leverage

▫️ Talent integration

▫️ Competitive positioning

They often begin with partnerships, co-sells, integrations, or shared customer wins. Reverse-engineering M&A history of likely buyers helps position early.

How do you assess exit potential in emerging sectors?

Ask:

▫️ Have similar companies exited recently?

▫️ Who were the acquirers and at what stage?

▫️ Is the space policy-driven or cyclic?

▫️ Are exits concentrated in rollups or secondaries?

Use PitchBook, CB Insights, or Crunchbase to map historical exit data by sector and round.

What financial metrics signal exit-readiness?

▫️ Gross Margin: >70% for SaaS is strong

▫️ Net Dollar Retention (NDR): >120% shows expansion

▫️ LTV:CAC Ratio: 3:1 or better

▫️ CAC Payback Period: Under 12 months

▫️ Burn Multiple: Below 1.5 preferred

▫️ Capital Efficiency: ARR/$ raised of 1.0+ is healthy

These tell a clear story of scalability and sustainability.

What is an exit waterfall and why does it matter?

An exit waterfall details how proceeds are distributed to shareholders during an exit. It considers:

▫️ Liquidation preferences

▫️ Participation rights

▫️ Conversion terms

▫️ Employee and founder equity

A $200M exit may seem great—until you realize late-stage investors take 90%. Modeling the waterfall early avoids painful surprises later.

How important is a startup’s narrative to its exit?

Crucial. Strong narratives:

▫️ Clarify strategic fit for acquirers

▫️ Align with macro trends (e.g., AI, security, climate)

▫️ Signal category leadership or ecosystem advantage

▫️ Simplify internal buy-in for buyers

The best exit stories are authentic but intentional. They show why the startup matters—and will continue to matter.

Can a startup exit without being profitable?

Yes—but it must show a clear path to profitability. Buyers look for:

▫️ Margin expansion

▫️ Cost controls

▫️ Efficient growth

▫️ Forecast credibility

Open-ended losses with no line of sight to break-even typically scare off acquirers and investors alike.

What tools or resources help evaluate exit potential?

▫️ PitchBook – M&A and IPO comparables

▫️ CB Insights – Sector exit trends and acquirer maps

▫️ Crunchbase – Company funding and acquisition histories

▫️ Carta/AngelList – Cap table analysis and simulations

▫️ Venture guides – e.g., Sequoia’s exit playbooks or a16z's exit models

When should you start discussing exit strategy with a founder?

Immediately after conviction—but before the first check. Early conversations help:

▫️ Align incentives

▫️ Surface dealbreaker mismatches

▫️ Inform valuation and dilution expectations

▫️ Ensure founder transparency and maturity

You can’t force an outcome, but you can reduce exit uncertainty with better up-front clarity.

How long does it usually take for a startup to exit?

▫️ M&A under $100M: Often within 5–7 years

▫️ Late-stage M&A or IPO: 8–12+ years

▫️ Emerging sectors (e.g., climate, hardware): Up to 15 years or longer

Fund lifecycle, LP expectations, and portfolio construction all impact what’s considered an “acceptable” timeline.

Can early-stage investors benefit from exits?

Yes, but only if:

▫️ They invest at a reasonable valuation

▫️ Cap table isn’t overly diluted

▫️ Liquidation preferences don’t wipe them out

▫️ Exits happen within their fund’s lifecycle

Understanding exit scenarios—especially with exit waterfall simulations—is critical to calculate expected returns.

Thank you, Ruben! Your analysis on startup exit strategy was extremely detailed and filled with in-depth knowledge of the field that reflects today's tighter markets. Emphasizing early alignment between founder intent and investor expectations was very persuasive and showed how this relationship between founder and investory really shapes the entire exit as a whole. I also found your explanation of exit-readiness—looking at cap table clean-up, unit economics, and narrative clarity—as a strategy that every company should from the very first day. I found this article to be an invaluable resource for both founders and investors aiming to achieve a meaningful exit rather than hoping one appears. Looking forward to future posts—thanks for sharing!

What's the percentage of startups from Europe that even get an exit?