Has Venture Capital Become “Return-Free Risk”?

Why Sequoia’s Roelof Botha says VC is overfunded, overhyped, and struggling to produce real exits in a $250B market.

We are seeing a lot of “unpopular opinions” being said out loud in recent months. It makes you think whether the Venture Capital industry has indeed changed.

Roelof Botha is a legend in VC, and his latest opinion didn’t appear out of nowhere. It was said twice. Once on the All-In podcast and then again on Uncapped.

“Investing in venture is a return-free risk.”

That line hit like a crack in the foundation. Not because it came from a skeptic or disillusioned outsider, but from the man steering Sequoia Capital, a firm synonymous with venture itself. Botha was one of the pioneers of modern tech companies, having been involved in the likes of PayPal, YouTube, Square, Unity, Instacart. His words carry weight not just inside Sand Hill Road, but across the entire risk capital spectrum.

That statement is hard to ignore, especially if you look at the math.

In a year where over $250 billion in VC funding has already been deployed, the number of true billion-dollar exits remains countable on two hands. So the problem is foundational. Not just of valuation compression or exit timing.

The venture capital engine which was long defined by asymmetric upside is now starting to look like a system that takes on risk without reliably delivering reward.

If even Sequoia’s math doesn’t work, what does that mean for founders, LPs, and the future of innovation?

Brought to you by Attio

The CRM used by both startups and VCs (including me)

I use Attio to manage deal flow, track founder conversations, and sync everything across my team — no clunky setup required.

Startups use it as a sales CRM from day one

VCs use it for deal tracking, LPs, and intros

Fully customizable and updates automatically

It’s fast, flexible, and built for how we actually work.

Table of Contents

1. The Context: When Sequoia Says “There’s Too Much Money”

2. The Math Problem: $250 Billion In, 20 Billion-Dollar Exits Out

3. When Too Much Money Hurts Returns

4. What This Means for Founders and LPs

5. Where Venture Goes Next

6. Venture’s Necessary Reset

1. The Context: When Sequoia Says “There’s Too Much Money”

Roelof Botha didn’t hedge. On Uncapped, he said it plainly:

“There’s a huge problem with the venture industry; there’s too much money.”

He then doubled down on the “All-In” podcast, arguing that more capital doesn’t produce more great startups. On the contrary, Botha believes that it can dilute execution, inflate valuations, and crowd out focus.

“Throwing more money into Silicon Valley doesn’t yield more great companies,” he warned. “It actually makes it harder for the ones that matter to stand out.”

Coming from the senior steward of Sequoia Capital, this is not just your average market commentary. Botha is part of the original PayPal mafia, a longtime general partner at one of the most iconic VC firms. When someone at that altitude questions the mechanics of the machine, you don’t dismiss it as cyclical hand-wringing. You simply pay attention.

Botha argues that the industry’s over-reliance on AI investing, especially in frontier and infrastructure plays, has created a capital gravity well. Billions of dollars are flowing into giants like OpenAI, Anthropic, Loveable, and Scale AI, while most other sectors stall.

And although he doesn’t deny AI’s promise, he emphasizes the risk of overshooting. Too much capital chasing too few foundational breakthroughs.

When the high priests of venture capital start doubting their own gospel, you know something’s changing.

2. The Math Problem: $250 Billion In, 20 Billion-Dollar Exits Out

In theory, more capital should mean more innovation. More bets placed, more winners found. But in venture capital, the numbers don’t work that way, and lately, they haven’t worked at all.

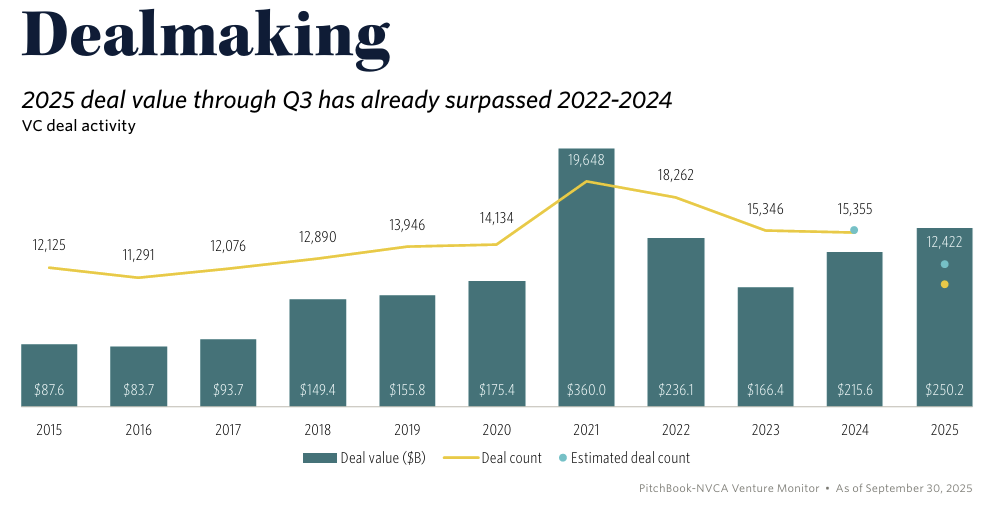

The reality is that the numbers back Botha’s claims. According to PitchBook’s Q3 Venture Monitor, global VC funding has surpassed $250 billion, but it’s mostly concentrated in a narrow set of mega-deals.

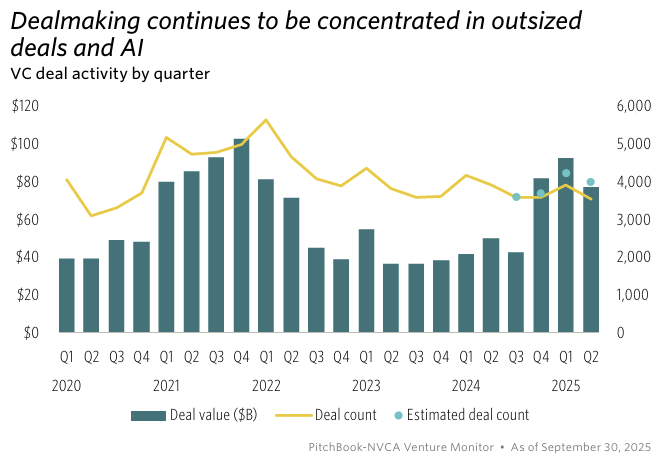

If you look closer, you’ll see that deal volume is down, exits remain scarce, and the top 10% of rounds account for more than half of capital deployed. This looks more like a storm surge around AI, and not just a rising tide.

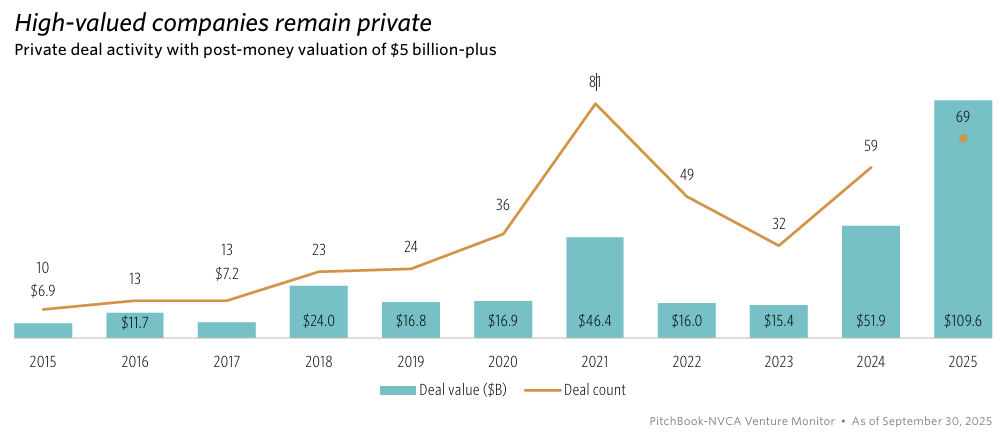

The biggest piece of bad news for VCs is that these billion-dollar unicorns are now choosing to remain private for longer.

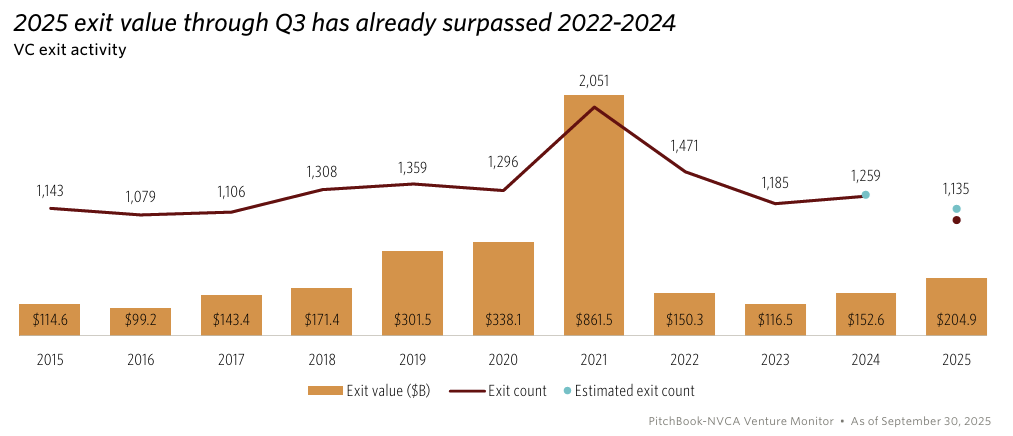

Finally, the number of true breakout exits - IPOs or M&A events north of $1 billion - remains stuck around 20 per year. This mismatch is now baked into how the system now functions.

Figma’s IPO was one the notable exits in 2025, which was used by Botha to make his point. Reflecting on Sequoia’s internal modeling, he said:

“There are only so many companies that matter. To justify this much capital, you’d need forty Figmas a year.”

And we’re not even close. Exit value in 2025 is trending around $200 billion, barely a quarter of what the industry saw in 2021. But the investment inputs have barely declined. So it looks like the machine is running hot, though the outcomes have cooled.

The problem isn’t that the averages are down, it’s that venture capital doesn’t run on averages. It runs on outliers.

A single mega-winner like Snowflake or Airbnb used to return entire funds. Now, with thousands of firms chasing the same limited set of unicorns, even being on the cap table isn’t a guarantee of DPI. Everyone’s playing power law roulette with a shrinking jackpot.

Botha’s point cuts deeper than cynicism. If you pour $250B into the system every year, but only a tiny sliver of companies break through, and only a fraction of those return real liquidity, then the core engine of venture starts to misfire. The risk remains, but the return disappears.

Can you see the paradox here? Venture isn’t failing because it’s broken. It’s failing because it’s too funded to function.

3. When Too Much Money Hurts Returns

On paper, 2025 looks strong. Consider record-setting AI rounds, dry powder measured in the hundreds of billions, and fund sizes that would’ve looked like growth equity just five years ago.

But underneath that, the system is bloated; distorted by excess liquidity in ways that actually sabotage the very outcomes it chases.

Valuation Inflation

When too much money chases too few truly high-potential startups, prices get irrational long before the public markets weigh in. The result is that entry points rise, but exit multiples compress, and IRRs collapse. What used to be a 10x becomes a 3x; or worse, a markdown.

Take OpenAI’s $40 billion round in early 2025. Or Anthropic’s billion-dollar raises across just 18 months. These are extraordinary companies, but the capital stacked into their cap tables sets such a high bar for exit that even massive commercial success may underdeliver for later investors.

Figma is also another example of an inflated valuation. After debuting with a 250% surge, the stock fell below its $33 IPO price just four months later. And that wasn’t because the business faltered, but because the private-market valuation simply ran ahead of what public markets were willing to sustain. In other words, if even a near-perfect company can’t hold its mark, it shows how excess capital inflates valuations beyond what real liquidity can support.

Talent Dilution

Money breeds startups. Startups need teams. But not every startup is built around a compelling idea, and not every team is built to execute.

The flood of funding since 2021 created a market where talent was spread thin, often across companies solving the same problems with less and less differentiation.

Execution mediocrity becomes systemic. Velocity slows. And in a power-law world, even minor stumbles erase the edge needed to become an outlier.

Exit Bottlenecks

Even if a startup is strong, the funnel narrows at the end. The public markets can only absorb so many listings, and M&A appetite remains muted. That’s why as of mid-2025, global exit value is still a fraction of 2021’s peak, despite capital deployment nearly matching it.

Companies that might’ve gone public in 18 months now sit in limbo for 4–5 years. GPs hold, hoping for the macro environment to get better. But waiting doesn’t bring liquidity. And when startup funding becomes a waiting game, returns dry up.

The Capital Feedback Loop

It’s not just founders who suffer from this situation. LPs are hit the hardest, because they watch distributions dry up too. DPI stagnates. So in response, they slow re-ups, cut exposure, and push for the secondary market. That squeezes GPs, who extend fund lives or chase higher follow-on rounds to prop up markups.

Thus, a loop is created:

Weak returns → cautious LPs → longer hold periods → stalled markets.

At some point, the system becomes too big for its own math. Money floods in faster than liquidity can flow out. The result is dislocation, not just underperformance. A venture ecosystem that’s technically healthy, but functionally jammed.

And that’s where we are now.

4. What This Means for Founders and LPs

When the venture capital engine slows, the impact ripples differently depending on where you sit. Although capital is not really vanishing, it’s actually narrowing. Power is concentrating.

For Founders: Fundraising Harder, Scaling Smarter

Money is still out there, but it’s no longer everywhere. In 2025, funding continues to flow into AI, lean startups, and defense tech; though selectively, and with more scrutiny.

Founders who raised easily in 2021 now find themselves in a different game. A game where every dollar must prove its worth. Raising too much, too early can backfire. High valuations lock founders into unrealistic growth curves. They burn faster, miss milestones, and struggle to reset. It’s the wrong kind of success; one that looks good on a TechCrunch headline but stalls in the long arc of company-building.

The founders who thrive now are the ones who combine capital discipline with strategic depth. They raise what they need, when they need it. They build around margins, not just market size. They treat dilution like a cost, not a deferral. And they know that in a risk-off cycle, hype takes the back seat, and the best moat is operational leverage.

For LPs: From Indexing to Intentionality

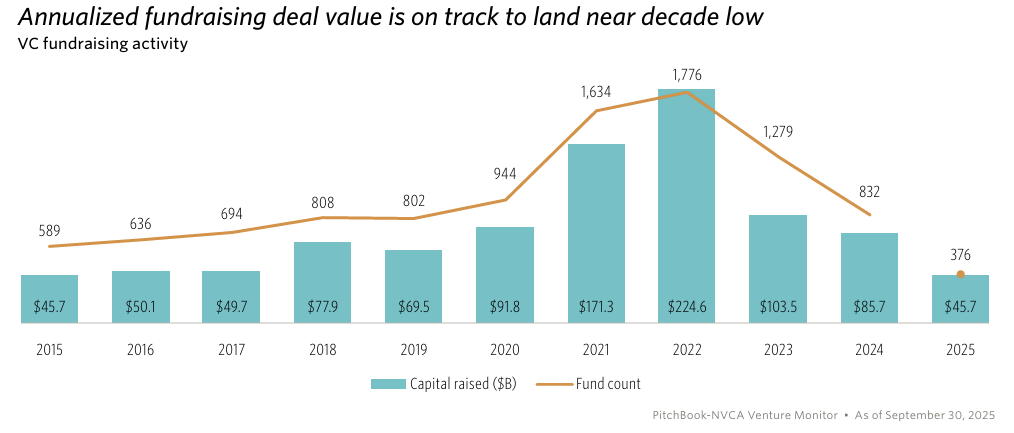

For limited partners, this cycle is a forcing function. According to the NVCA, venture fundraising in 2025 has slowed to 2017 levels. And that’s not because LPs lack interest, but because they’re rethinking how they participate.

The big change is that venture is no longer an asset class in the traditional sense. You can’t buy the market and expect median returns to deliver. You have to underwrite individual managers, based on their strategy, judgment, discipline, and track record.

LPs who continue allocating passively will miss the signal. The best LPs today have already stopped diversifying, and are now concentrating. They’re pacing capital more carefully. They’re negotiating for secondaries and co-invest rights. They’re betting not on venture as a category, but on the few GPs who still have edge.

In a world where VC returns are uneven and exits remain uncertain, selectivity becomes the baseline.

5. Where Venture Goes Next

If the past three years exposed the cracks in the VC model, the next three will define how, or if, it adapts.

The old assumptions are gone. Fund size is no longer a flex. Spray-and-pray doesn’t work when exits stall. LPs aren’t indexing, founders aren’t fundraising for the sake of it, and GPs can’t rely on “market momentum” to carry weak companies across the DPI finish line.

So where does venture capital go from here?

AI as Gravity Well

As of mid-2025, AI accounts for more than 60% of global venture funding. It’s not just a sector, its become a veritable force field. The capital, talent, and infrastructure weight around generative AI, foundation models, and frontier compute is distorting everything around it.

That kind of dominance creates concentration risk. LPs are overexposed to the same handful of firms. GPs are clustering in the same thesis space. And startups in adjacent categories are either rebranding to “AI” or watching their cap tables dry up.

Surely, AI is set to define the next decade, but in venture terms, it’s now a zero-sum arena. Most of the upside will accrue to a few companies, and everyone will evaporate.

The Rise of Roll-Up and Venture-PE Hybrids

In response to this change, some investors are building horizontally, not just betting on one startup, but buying and stitching together clusters.

The “venture roll-up” model is growing. How this model works is by acquiring capital-efficient SaaS or infra-AI firms at low multiples, integrating them into coherent platforms, and selling to strategics or the public markets. It’s a move borrowed from private equity, but run through the speed of a startup.

It’s less romantic than early-stage betting, but in a liquidity-starved world, aggregation creates optionality.

Evergreen and RIA-Style Funds

The standard 10-year closed-end structure feels increasingly mismatched to modern startup trajectories. Companies take longer to exit, LPs want liquidity optionality, GPs want more flexibility in pacing and compounding.

Enter the evergreen venture model. That means funds with no fixed term, often modeled like RIA-style structures (Registered Investment Advisors), where fees are tied to realized performance, not paper markups. A handful of big firms such as General Catalyst, Lightspeed and Sequoia are experimenting with these now, aiming for durability over decade math.

In a world where time is the enemy of liquidity, new structures might just be venture’s next frontier.

Specialization Renaissance

The age of the generalist is fading. The firms gaining LP trust, and founder mindshare, are now those with domain edge. VCs that specialize in deep sectors like bio, climate, defense, AI, fintech infra.

Such specialization brings operating advantages - deep networks, regulatory fluency, and real empathy with technical founders. In a more skeptical, risk-selective world, brand means less, context means more.

Expect to see fewer “multi-stage” strategies and more verticalized, conviction-driven platforms.

Fewer Firms, Deeper Conviction

Venture isn’t dying, clearly, but it’s resizing itself for reality.

The long tail of mediocre firms, like those surviving on paper returns, loose markups, and proximity to hot rounds.. they won’t make it. The new equilibrium will be smaller, tighter, more trusted. What that looks like is fewer logos and more signal.

And that’s good news for founders. It means fewer tourist checks. More lead partners who actually show up.

For LPs, it’s a call to go deeper instead of wider.

6. Venture’s Necessary Reset

“Investing in venture is a return-free risk.”

Roelof Botha didn’t mean it as a eulogy. He meant it as a diagnosis, and, implicitly, a prescription.

The past few years exposed all the excess. Excess capital raised faster than conviction could keep up, excess valuations untethered from outcomes, and a funding machine running on speed instead of signal.

What this all means is that the engine is overdue for recalibration.

The next chapter of venture capital will be smaller, slower, and smarter. It’s going to be less about paper markups, more about realized impact. Less about chasing froth, more about underwriting innovation with depth. It won’t be as loud, but it might be healthier.

If you’re a founder, the invitation is clear. You are asked to build for durability. To not chase hype. If you’re a GP, sharpen your edge and earn your next allocation. If you’re an LP, stop indexing and start selecting.

In a world where capital is no longer the bottleneck, judgment is the differentiator.

As one chapter closes, another one begins. This might be the start of a better chapter for venture capital.