Startup Valuation Methods: 8 Approaches Investors Use

Prepare for your next funding round by diving more into the 8 most common valuation methods investors use.

Whether you’re raising capital, prepping for an acquisition, or issuing equity to your team, the valuation you land on shapes the entire deal. It sets the tone for how much ownership you give up, how investors view your business, and what future fundraising looks like. Yet most early-stage founders aren’t clear on how investors actually arrive at those numbers.

The truth is, VCs and angels don’t rely on a single formula. They use a mix of methods based on your stage, traction, and market. Understanding these approaches helps you frame your ask better, avoid common traps, and negotiate with more confidence.

🚀 Win Enterprise Clients—Without the Overhead

Selling to enterprise? Vanta, Synthesia, and HubSpot break down how fast-growing startups can land big deals and meet tough security expectations in this expert-led webinar.

✅ Identify and influence key decision-makers

✅ Build security credibility quickly

✅ Streamline complex enterprise sales cycles

Walk away with proven strategies to sell smarter, scale securely, and make the enterprise leap—without stretching your team thin.

Table of Contents

The Berkus Method: Valuing Potential Over Revenue

Comparable Transactions: The Startup "Comps" Approach

Scorecard Valuation: Adjusting for Local Strengths

Cost-to-Duplicate: Rebuilding from Scratch

Risk Factor Summation: Quantifying Uncertainty

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF): The Financial Forecast Model

Venture Capital Method: Exit-Driven Estimation

Book Value Method: Net Worth of the Startup

Which Valuation Method Should Your Startup Use

1. The Berkus Method: Valuing Potential Over Revenue

If your startup doesn’t have revenue yet, the Berkus Method is a solid place to start. It was designed for early-stage founders who are still building — maybe you have a prototype, maybe just a slide deck — but no numbers to back up a financial model.

Here’s how it works: investors break your startup into five categories — the idea itself, the strength of your team, how far your product has come, the product’s launch readiness, and any strategic relationships you’ve lined up. Each category is assigned a dollar amount, often up to $500K each. Add them together, and that’s your pre-money valuation.

It’s simple.

It forces everyone to focus on what actually matters at this stage, and that is reducing risk. The more you’ve de-risked each area, the higher your potential valuation.

But it’s also subjective. What looks like a great team to you might seem inexperienced to a seasoned investor. And once you start generating revenue, Berkus won’t be enough on its own.

Founder tip: Don’t just check boxes. Show progress in each of the five areas. If you have early feedback on your prototype, mention it. If you’ve brought on an advisor with industry connections, that’s leverage. Use Berkus as your early narrative, not your final pitch.

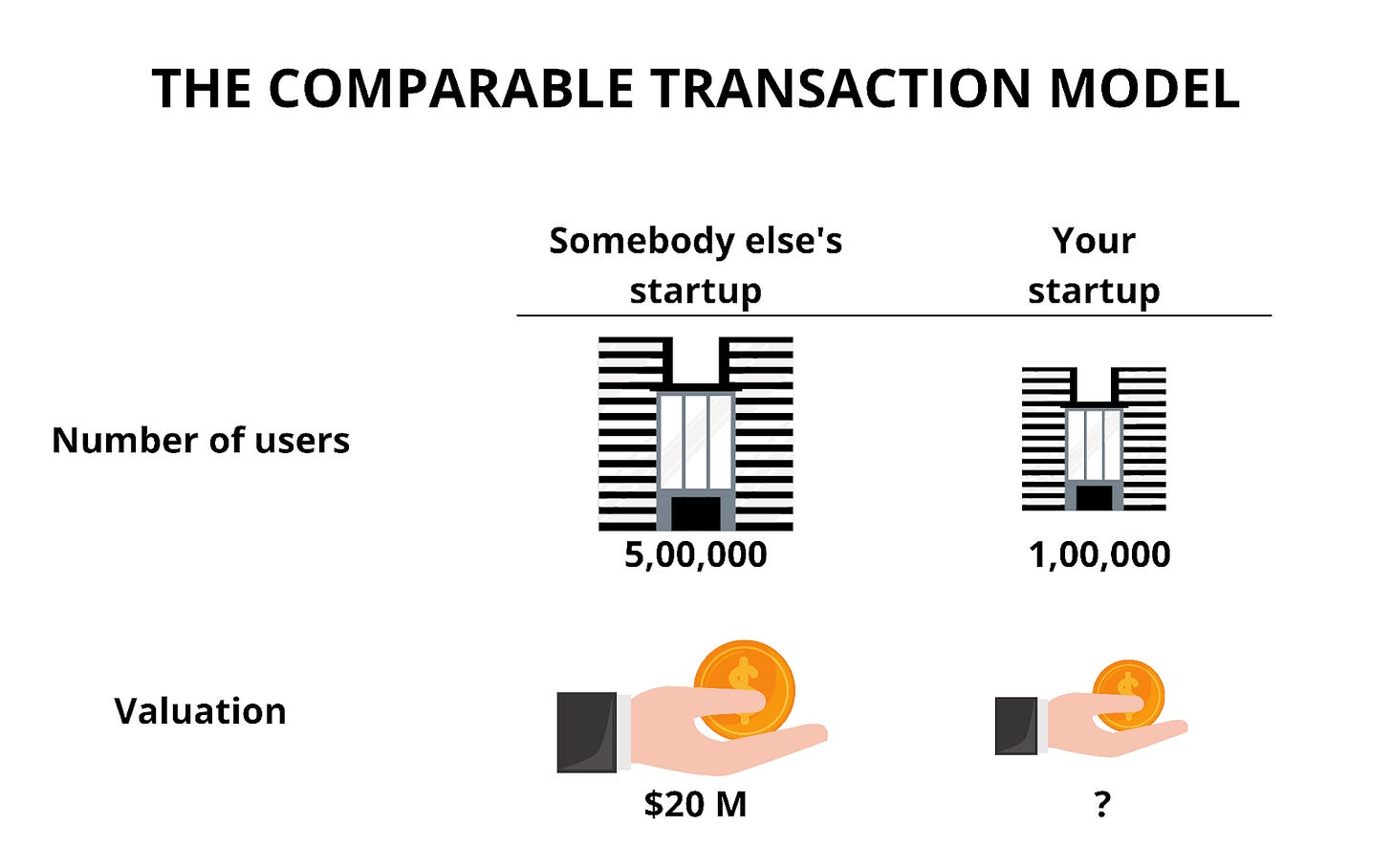

2. Comparable Transactions: The Startup "Comps" Approach

This is one of the most common methods used by VCs, bankers, and acquirers, and for good reason. The Comparable Transactions method looks at how similar startups have been valued in recent funding rounds or acquisitions. If startups like yours are raising at $20M pre-money, it sets a baseline for what the market is willing to pay.

The logic is simple.

Find relevant deals, extract the valuation multiples (like revenue or user-based), and apply them to your own numbers. For example, if SaaS startups at your stage are getting 8× ARR and you’re doing $2M ARR, your implied value might sit around $16M.

But here’s the catch: good comps are hard to find. Many deals are private. The details are often fuzzy. And what looks like a similar company on the surface might have different margins, markets, or teams.

Founder tip: Use comps as a credibility tool, not a crutch. If you’re anchoring to market data, be ready to explain why those startups are truly comparable, and what makes you more (or less) valuable. Investors will challenge the fit. Be prepared.

3. Scorecard Valuation: Adjusting for Local Strengths

The Scorecard Method starts with one question: What’s the going rate for startups like yours in your region? If most pre-seed rounds in your city are getting $3 million pre-money, that becomes the baseline.

From there, investors adjust up or down based on how your startup stacks up against others in key areas, like team quality, market size, product, traction, and competitive landscape. Each factor has a weight.

Maybe the team counts for 25%, the market size for 20%, and so on. If your team is stronger than average, that part gets a boost. If your go-to-market looks weak, that portion might get docked.

According to Eqvista, some of the most common scorecard criteria are:

Board, entrepreneur, the management team – 25%

Size of opportunity – 20%

Technology/Product – 18%

Marketing/Sales – 15%

Need for additional financing – 10%

Others – 10%

So, let’s say your weighted score comes out to 110% of the local average. If the average valuation is $3M, your adjusted valuation becomes $3.3M.

This method is popular with angel groups because it blends local market data with structured judgment. But it depends heavily on having accurate benchmarks and honest comparisons.

Founder tip: Have your data ready; know the average valuation in your area and stage. And when pitching, don’t just say you’re better, explain why. Highlight what makes your team, market, or product stand out. That’s how you earn the premium.

4. Cost-to-Duplicate: Rebuilding from Scratch

This method asks a basic but important question: how much would it cost to build your startup from the ground up, today?

The Cost-to-Duplicate approach estimates the value of your business by adding up everything it took (or would take) to recreate it. That includes engineering time, salaries, tech infrastructure, R&D, hardware, patents, and other tangible investments.

If you’ve spent $1.2M building a working prototype, hiring a dev team, and launching your first version, then your valuation might be anchored somewhere around that figure.

Investors sometimes use this as a floor, a minimum valuation based on the effort already invested. It's particularly relevant for asset-heavy startups or those with deep tech, where replicating the product is expensive.

But this method has a blind spot. It doesn't factor in the upside. If you're solving a huge problem with high margins and a scalable model, those aren’t reflected in cost alone. A lean team that built something valuable on a tight budget might deserve a much higher valuation than the cost implies.

Founder tip: Calculate your cost to build and have it handy. It’s a good fallback if investors push back on price. But don’t stop there. Anchor the conversation in traction, market size, and vision to push beyond the minimum.

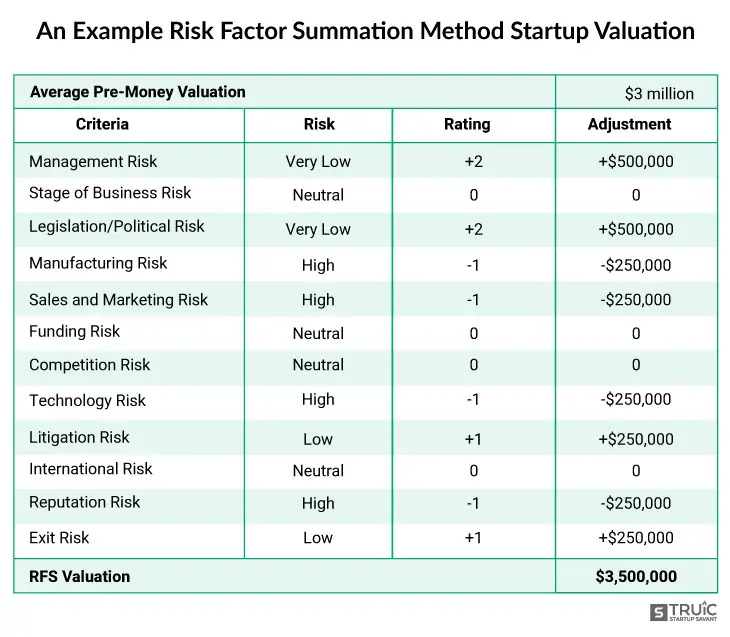

5. Risk Factor Summation: Quantifying Uncertainty

This method takes a structured approach to something every investor already does - assess risk. The Risk Factor Summation Method starts with a base valuation, often the average pre-money for startups at your stage, and adjusts it up or down based on 12 specific risk categories.

These include things like technology risk, market competition, legal or regulatory hurdles, funding needs, sales and marketing execution, and the strength of your management team. Each risk is scored on a scale from very positive to very negative, and each score adds or subtracts a fixed amount (typically $250K) from the base valuation.

Let’s say the average valuation in your sector is $3M. An investor might score your startup +1 for a strong team (+$250K), +2 for clear exit potential (+$500K), but -1 for tech complexity (-$250K) and -2 for intense competition (-$500K). Net adjustment: -$0. The final valuation stays at $3M.

Here’s another example:

The method is comprehensive and forces investors to think through risk logically. But it’s still subjective, and scoring varies from person to person.

Founder tip: Ask which risks matter most to an investor. If you can mitigate or reframe those concerns, you may be able to shift the math in your favor.

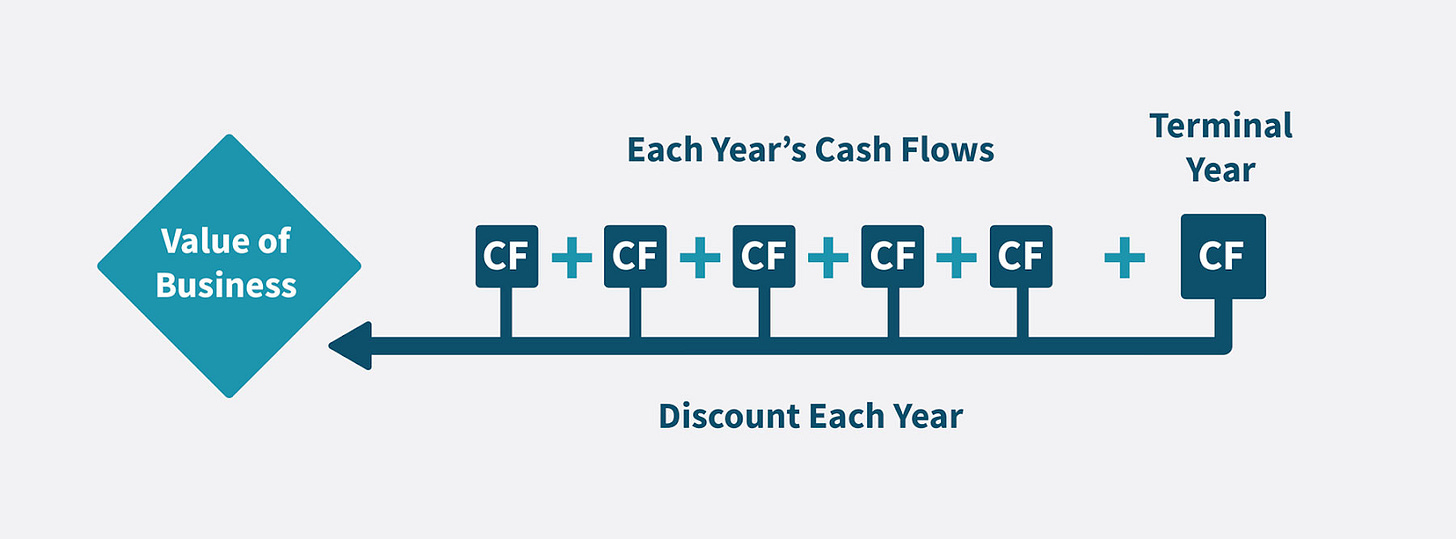

6. Discounted Cash Flow (DCF): The Financial Forecast Model

DCF is one of the most rigorous valuation methods out there. It’s built on a simple idea - a business is worth the money it will generate in the future, adjusted for the risk of actually getting there.

You start by projecting your startup’s future cash flows over the next 5 to 10 years, estimate what the company might be worth at the end of that period (the terminal value), and then discount everything back to today’s value using a required rate of return. The higher the risk, the higher the discount rate, and the lower the present value.

This method is great for startups with steady revenue and visibility into growth, typically post-Series A or later. But in early-stage deals, DCF often falls apart. Forecasts are guesses, and discount rates are aggressive. A small change in assumptions can swing the valuation dramatically.

Founder tip: DCF can help you understand the long-term economics of your model. But if you’re still figuring out pricing or CAC, keep it simple. Investors won’t expect you to forecast 10 years, they just want to know you’ve thought ahead with realism.

7. Venture Capital Method: Exit-Driven Estimation

The Venture Capital Method works backward from the endgame. It starts with a projected exit, through acquisition or IPO, and calculates how much a VC needs to invest today to hit their target return.

This method is usually done in 6 steps:

Estimate the Investment Needed

Forecast Startup Financials

Determine the Timing of Exit (IPO, M&A, etc.)

Calculate Multiple at Exit (based on comps)

Discount to PV at the Desired Rate of Return

Determine Valuation and Desired Ownership Stake

Here’s the basic flow - estimate your exit valuation (say, $100M in 5 years), then apply the investor’s desired return, often 10x or more. If they want 10x, your startup needs to be worth $10M today. Subtract the size of the investment, and you get your pre-money valuation.

This method is fast and common in VC conversations because it ties valuation to actual returns. But it’s also rough. It assumes a successful exit and glosses over all the twists and turns in between.

If a VC thinks your company could exit at $100M and wants a 10x return, they’ll only invest if they can get in at a $10M post-money. If you’re raising $2M, that puts your pre-money at $8M.

Founder tip: Know the math investors are doing behind the scenes. You can’t control their return targets, but you can influence the exit assumptions. Make a credible case for why your business could be a $100M+ outcome, and back it up with market logic.

8. Book Value Method: Net Worth of the Startup

This one’s as old-school as it gets. The Book Value Method calculates your startup’s value by subtracting liabilities from assets, essentially, what the company is worth on paper if it shut down today.

It’s grounded in accounting, not projections. Cash, inventory, equipment, and any recorded IP count as assets. Loans, payables, and other debts are liabilities. The difference is your book value. For example, if you have $1.5M in assets and $500K in liabilities, your book value is $1M.

This method makes sense in very specific cases like asset-heavy businesses, liquidation scenarios, or internal transfers. But for high-growth startups, it rarely tells the full story. A lean SaaS company with big upside might have almost nothing on the books, just a few laptops and some code.

Founder tip: Don’t lead with book value unless your assets are a real part of the story. But make sure your books are clean; a strong balance sheet can still signal financial discipline, especially in late-stage or acquisition talks.

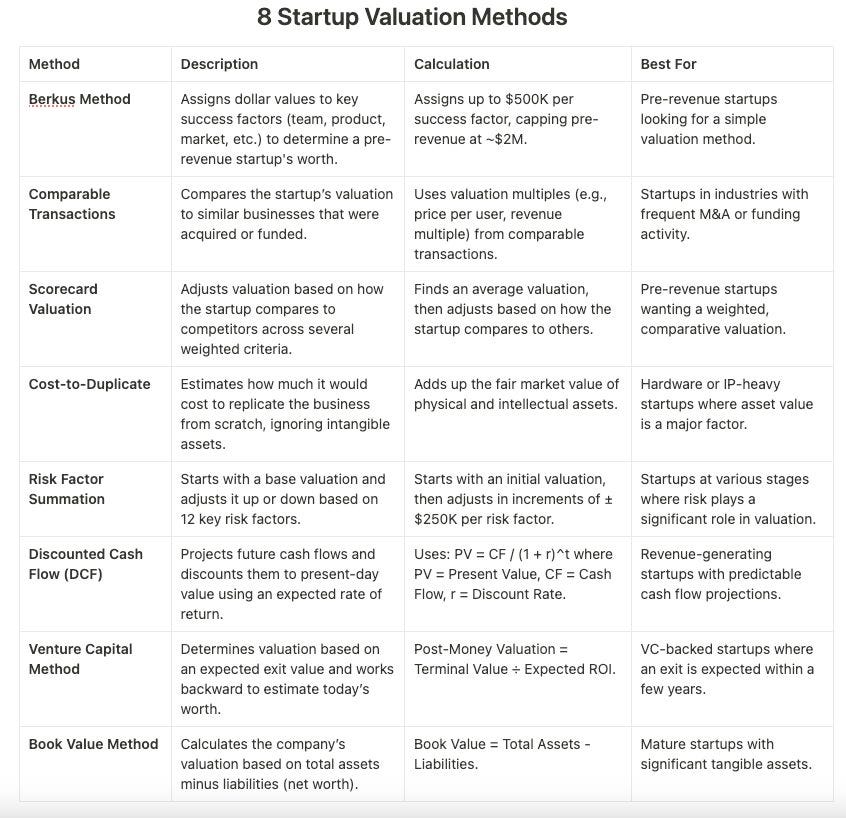

9. Which Valuation Method Should Your Startup Use?

There’s no single right answer, and that’s the point. The best valuation method for your startup depends on your stage, industry, revenue visibility, and the type of investor across the table.

If you’re early and pre-revenue, lean on methods like Berkus, Scorecard, or Risk Factor Summation. If you’ve launched and have traction, Comparable Transactions and Cost-to-Duplicate help anchor expectations.

Once revenue kicks in, DCF or the VC Method becomes more relevant. And for asset-heavy or late-stage startups, Book Value might enter the picture.

The smart move is to triangulate using 2–3 methods. This gives you a range, not just a number, and shows you’ve thought through valuation from different angles.

Example 1:

A pre-seed SaaS startup with a prototype and no revenue might blend Berkus (to value progress), Scorecard (to align with local deal norms), and Risk Factor (to adjust for execution risk).

Example 2:

A Series A e-commerce startup doing $3M in revenue could use Comparable Transactions, a light DCF, and the VC Method to frame its next round.

Whatever stage you’re in, use valuation methods as tools, not absolutes. The number matters, but the story behind it matters more.

Resources for founders

These resources are part of a growing library of resources designed to help startup founders raise capital, grow smarter, and move faster.

✅ Ultimate Investor List of Lists: +10k VCs, BAs, CVCs, and FOs

✅ 70+ Startup Pitch Decks That Raised Over $1B

✅ The VC Method Excel Template

✅ 50 Game-Changing AI Agent Startup Ideas for 2025

✅ The 100+ Pitch Decks That Raised Over $2B

✅ SAFE Note Dilution: How to Calculate & Protect Your Equity (+ Cap Table Template)

✅ 118 AI Communication Agent Use Cases

✅ AI Co-Pilots Every Startup & VC Needs in Their Toolbox 🛠️

✅ The Startup Founder’s Guide to Financial Modeling (7 templates included)

✅ The Best 23 Accelerators Worldwide for Rapid Growth (and How to Get Into Them)

✅ The Ultimate Startup & Venture Capital Notion Guide: Knowledge Base & Resources

These resources are part of a growing library of resources designed to help startup founders raise capital, grow smarter, and move faster.

Solid breakdown of the valuation toolkit. One thing I've noticed in practice is that the VC Method and DCF often produce wildly different numbers for the same company, which creates interesting negotiation dynamics. Founders anchoring on DCF projections while investors work backward from target returns. The Berkus and Scorecard methods are underrated for pre-seed; they force qualitative rigor when there's no financial data to model. Would love to see a follow-up on how these methods interact in actual term sheet negotiations.