The Onion Theory of Startup Risk: The 5 Layers Every Investor Evaluates

From Marc Andreessen’s insight to modern founder playbooks: how peeling away uncertainty builds value, raises rounds, and shapes the next generation of startups.

The Onion Theory of Risk

Every startup is born inside a fog of uncertainty. Founders talk about valuation methods, traction, and product-market fit as if they were fixed targets, but they’re all really just reflections of how much risk the company has removed from its story.

When investors decide what a startup is worth, what they effectively do is discount its unresolved risks. And that’s where it becomes important to understand and appreciate the “Onion Theory of Risk”.

First introduced by Andy Rachleff and popularized by Marc Andreessen, the metaphor reframes startups not as idea machines but as risk machines, with each one built around layers of uncertainty that must be peeled away over time.

Every layer represents the most common investor concerns. That could be the wrong team, unproven demand, technical fragility, or capital inefficiency.

And as execution removes those layers, confidence grows, valuation climbs, and fundraising gets easier. It’s a process of systematic de risk.

Some of those layers don’t come from product or market at all. They show up later, around Series A, when operational decisions start compounding.

That’s why this change matters:

👉 HubSpot has moved its Series A startup discount from 50% to 90% for Year 1, matching the deal seed stage companies get. It applies to CRM, AI features, and includes dedicated onboarding.

In practice, that means Series A teams can lock in a system of record without taking on the usual pricing risk that comes with scaling infrastructure too early.

The discount applies to:

HubSpot’s CRM platform

AI capabilities via HubSpot Credits

Dedicated onboarding and support to reduce migration friction

It also extends beyond Year 1, with 50% off in Year 2 and 25% off in Year 3, which matters if you’re thinking in terms of multi-year operating leverage, not just quick wins.

As support volume grows, built-in AI helps teams keep up without adding headcount.

If you’re at Series A and thinking about consolidating your stack, this is worth locking in early while it’s available:

Table of Contents

1. The Origin and Evolution of the Onion Theory

2. The Five Layers Every Investor Evaluates

3. How the Onion Framework Defines the Fundraising Strategy

4. How Investors Actually Use the Onion Theory

5. Turning Metaphor Into Metrics

6. How the Onion Explains Valuation and Negotiation

7. Advanced Insights and Sector Nuances

8. Building a Risk-Driven Company

1. The Origin and Evolution of the Onion Theory of Risk

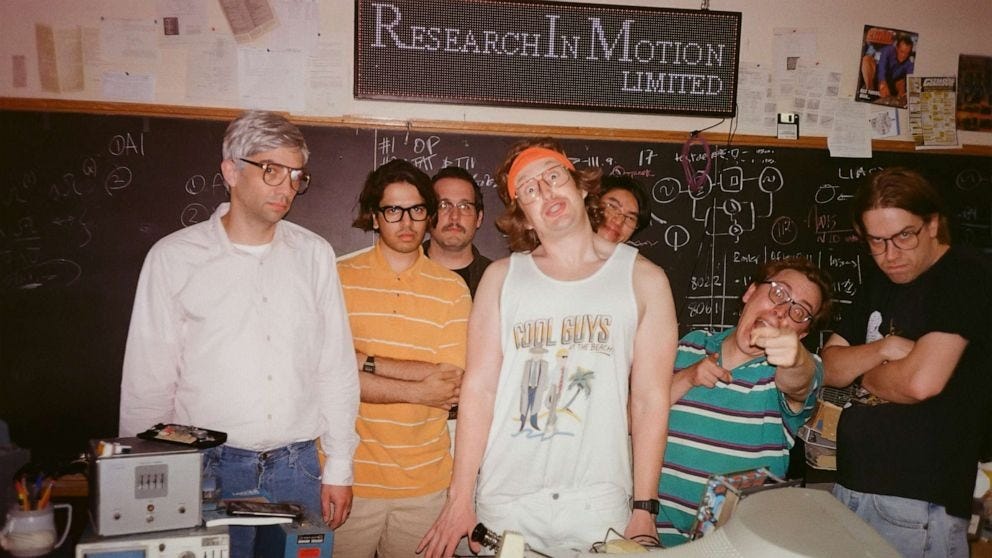

The Onion Theory of Risk began as a practical mental model inside the early venture capital world. Andy Rachleff, co-founder of Benchmark Capital and one of the architects of modern VC thinking, used it to teach how investors evaluate uncertainty.

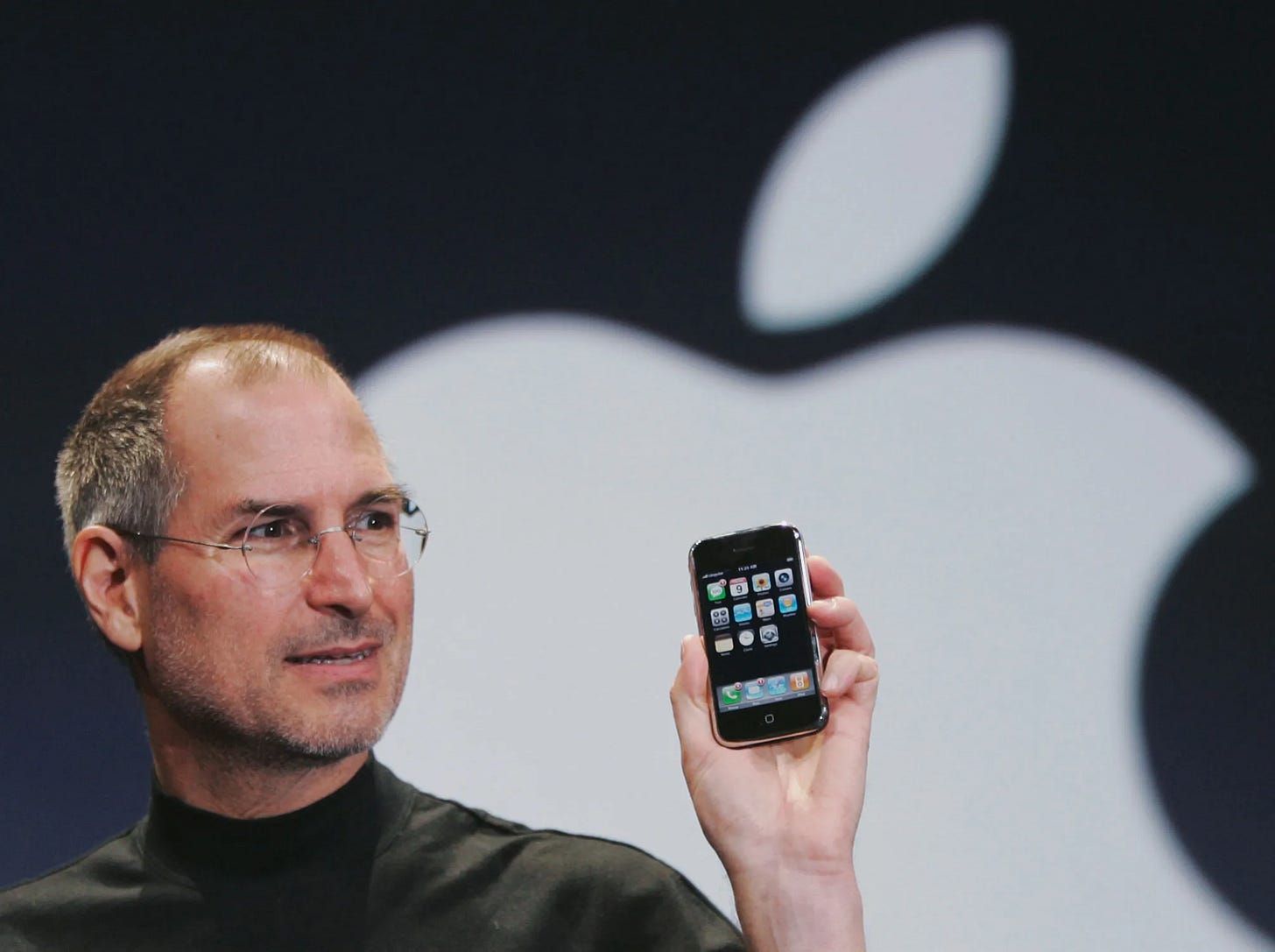

Marc Andreessen later popularized the metaphor by describing every company as “an onion of risk” that must be peeled layer by layer until an investment “no longer looks terrifying, only risky.”

The simplicity of the analogy disguised its depth and reframed startup building as an act of progressive de-risking a startup rather than linear scaling.

Its intellectual roots trace back to three schools of thought that shaped modern entrepreneurship. From stage-gate innovation, it inherits the idea that progress is proven by evidence at each gate before more capital flows.

From the Lean Startup strategy, it borrows the discipline of testing hypotheses quickly and converting uncertainty into learning.

And from real-options theory, it mirrors the logic that each milestone increases a venture’s option value by buying down uncertainty.

In effect, the Onion Theory compresses these ideas into a founder’s version of the investor’s playbook. It becomes a shared language for quantifying unknowns.

Over time, investors like Jon Lai of a16z and others have extended the framework into operational practice. They use it not as a metaphor, but as a progress map. A way to model which risks have been retired and which remain coupled.

And the framework endures because it’s one of the few that bridges both sides of the table.

Founders can use it to plan and communicate milestones, while investors use it to justify valuation, reserves, and pacing. That mutual visibility is why, two decades later, the Onion Theory remains a cornerstone of venture reasoning, a shared grammar for turning the chaos of early-stage building into a measurable sequence of learning.

2. The Five Layers Every Investor Evaluates

Although startup begins as a bundle of unknowns, not all risks are created equal. Experienced investors create a startup risk framework by grouping risks into recognizable families, each representing a dimension of uncertainty that can either be peeled away through execution or left unchecked to compound into failure.

Understanding these families gives founders a diagnostic map, a way to see what’s blocking progress and what proof will unlock the next stage of value.

1. People and Execution Risk

What investors want to know: Can this team actually build what they say they will?

People risk sits at the core of the onion because everything else is downstream of capability and chemistry. Investors assess whether the founders have complementary skills, relevant experience, and the discipline to adapt under pressure.

Evidence that reduces it:

A complete founding team with technical and commercial balance.

Prior execution in adjacent domains (operator history, shipped products, leadership in complex builds).

Early hires that fill key gaps, e.g., engineering leadership or GTM roles.

How founders measure progress: Team composition is measured by how fast critical roles are filled, how consistently goals are met, and how well decisions translate into shipped outcomes.

2. Product and Technical Risk

What investors want to know: Is the product technically feasible and functionally sound? Can it scale?

This layer captures everything from engineering difficulty to product quality to defensibility. A founder’s biggest credibility builder early on is proving they can make what they imagined.

Evidence that reduces it:

Functional MVP or prototype demonstrating core capability.

Patents, defensible IP, or proprietary data loops.

Early customer usage validating performance and reliability.

How founders measure progress: Milestones like prototype release, uptime, latency metrics, or user satisfaction scores serve as startup risk management or risk clearance signals. Technical breakthroughs and architectural stability unlock subsequent layers such as market validation and revenue modeling. Without this, everything else is hypothetical.

3. Market and Demand Risk

What investors want to know: Does anyone actually want this?

Even the perfect product will fail if the market is too small or timing is off. Investors want to see proof that there’s real pull, such as early users, paying customers, or usage growth that suggests genuine need.

Evidence that reduces it:

Retention cohorts proving repeat usage.

Signed LOIs, pre-orders, or paid pilots.

Organic referrals or virality without excessive marketing spend.

How founders measure progress: Activation rate, retention, and conversion are the key metrics here. Founders who instrument usage early can show that demand is real and repeatable. Market risk often couples with timing. Launch too early and adoption lags, too late and incumbents dominate. The only antidote is live feedback from real customers.

4. Economic and Financial Risk

What investors want to know: Can this business make money at scale?

Investors aren’t just looking for growth. They want to see unit economics that improve with scale. This layer measures pricing power, margins, CAC payback, and capital efficiency.

Evidence that reduces it:

Early revenue with healthy gross margins.

CAC vs. LTV ratio showing path to profitability.

Controlled burn multiple (<2× in early growth).

How founders measure progress: Use cohort-level contribution margin and payback metrics to show improving efficiency. The faster a startup converts capital into risk reduction (risk burn efficiency) the higher its credibility.

5. Contextual and External Risk

What investors want to know: What’s outside your control that could break the business?

This category includes regulatory, geopolitical, and macroeconomic factors. For example, a fintech company usually faces licensing hurdles, while a biotech faces clinical approval, and an AI company faces data compliance risk.

Evidence that reduces it:

Regulatory approvals, compliance certifications, or sandbox participation.

Strategic partnerships with incumbents or regulators.

Clear go-to-market frameworks aligned with legal constraints.

How founders measure progress: Be involved in everything and maintain a startup risk management ledger. That’s a living record of external dependencies and mitigations. For instance, tracking compliance milestones or mapping supplier concentration helps quantify exposure. Unresolved compliance risk can freeze fundraising or delay product rollout.

Interdependence and Coupling

Remember that no layer exists in isolation. A weak team magnifies product risk, an uncertain product value inflates market risk, an unresolved compliance issue delays monetization.

Building a startup is nonlinear. The job of a founder is not to eliminate all risks at once but to sequence their removal intelligently, peeling layers in the order that unlocks the next proof point.

The more methodical this peeling process, the faster uncertainty turns into evidence, and evidence into valuation.

3. How the Onion Framework Defines the Fundraising Strategy

Every round of capital buys down a few layers of risk, and the smartest founders raise with that sequence in mind.

The Onion Theory of Risk turns fundraising from a negotiation over valuation into a plan for risk retirement.

When investors decide whether to fund a company, they’re implicitly asking one question: “What risks have you already peeled away, and what will this capital retire?”

Founders who can answer that clearly create confidence and pricing power. The rest rely on narrative and get priced on hope.

Mapping Capital to Risk Retirement

The simplest way to visualize this is as a risk roadmap.

This progression shows that fundraising doesn’t just give you enough runway, it also validates proof. The goal of each round is to collect enough evidence to make the next one inevitable. The more risk you retire per dollar, the more control you retain over valuation and dilution.

Framing the Narrative

Top founders risk compression. Their decks often include these two slides:

“Here’s what we’ve de-risked since our last round.”

“Here’s what this round will de-risk next.”

This framing does three things at once. It telegraphs discipline, it shows clarity of execution, and it invites investors into a story of compounding proof.

When you articulate your startup as a risk-retirement machine, investors immediately understand what the next milestone means and why now is the right time to invest.

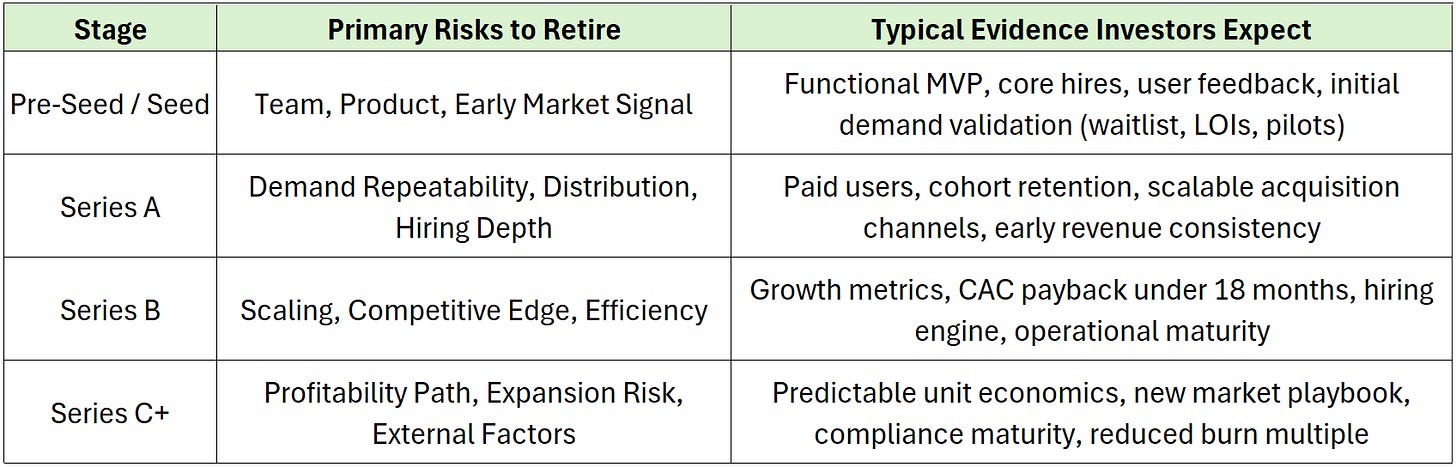

Investor Expectations by Stage

VCs rarely say it explicitly, but each stage comes with its own risk threshold:

At Seed, investors tolerate high uncertainty but need evidence of team and product viability.

At Series A, they expect signs of product-market fit and repeatable growth loops.

At Series B, they want proof of scaling efficiency and early signs of defensibility.

Beyond Series C, they expect systems-level predictability: steady margins, compliance maturity, and optionality for expansion or exit.

What separates elite founders from everyone else is how tightly they align capital to that journey. Each dollar raised should peel away a visible layer of fear in the investor’s mind.

When cash buys learning faster than it buys comfort, you’re doing it right. When it buys comfort without learning, the next round gets harder.

4. How Investors Actually Use the Onion Theory

Top investors perceive valuation as a mirror of residual risk. The more layers a founder has peeled away, the less discount they apply.

Every investment committee discussion, regardless of stage or style, eventually revolves around one question: “How much uncertainty remains, and how efficiently is this team removing it?”

The Onion Theory of Risk is the best way to quantify that intuition, and it shows founders exactly how their business is being scored behind closed doors.

Inside the Investment Committee Logic

When a partner brings a deal to their firm, the first internal discussion is usually about risk mapping, and then it becomes about market size or storytelling polish.

Each committee member mentally lays out the startup risk framework, or the startup’s risk layers covered earlier and asks which have been peeled, which remain coupled, and which could cascade if left unresolved?

This is why due diligence checklists feel repetitive across firms. They aren’t supposed to be arbitrary. They’re purposely structured to test whether claimed risk reductions are real.

A working prototype peels product risk; early customer retention peels market risk. But if technical scalability is still uncertain, or burn rate is high, those layers stay thick. The committee will flag that coupling and adjust check size or pricing to compensate.

Risk Coupling and Risk Burn Efficiency

Investors think in relationships between risks, not just in lists. A coupled risk is one that blocks or amplifies another, like weak demand masking poor product fit, or a single founder magnifying both execution and hiring risk.

Such couplings are dangerous because they compound uncertainty. Most experienced VCs will fund only when a startup has shown the ability to decouple at least two of its biggest risks.

Then comes risk burn efficiency (RBE), a measure of how much risk a team removes per dollar spent. If $1 million led to a validated product, two hires, and customer proof, efficiency is high. If it led to vague experiments and no clear learning, efficiency is low.

Using Risk to Size Checks and Structure Rounds

Check size isn’t determined by founder confidence but by how much risk the next tranche of capital can realistically retire. If a seed company needs six months to prove user retention and finalize a build, an investor might cap funding to that scope. At Series B, when risks transition from product to scale, checks get bigger because the cost of peeling each layer grows.

Valuation follows the same logic. If 70% of major risks are retired, investors reduce their required discount rate, pushing the price up. If those risks remain, even a strong narrative can’t justify premium pricing.

Negotiation, then, becomes a translation of risk into capital. Less about dreams, more about proof.

Different Investors, Different Risk Appetites

Not all capital treats risk equally. Seed and pre-seed funds are built to absorb uncertainty by pricing upside instead of traction.

Growth-stage investors, on the other hand, are looking to buy predictability. They want risk peeled, data verified, systems in place.

Institutional crossover funds expect to see entire categories of risk retired before entering: customer churn, regulatory exposure, and dependence on a single channel must already be under control.

As a founder, understanding this gradient is power. You don’t need to de-risk everything at once, you need to know which investor archetype prices which kind of uncertainty.

That’s how you walk into a room already speaking their language.

5. Turning the Metaphor Into Metrics

The Onion Theory of Risk may have started as an analogy, but in practice it’s a management system. Founders who treat “de-risking” as a measurable process build faster, raise easier, and waste less capital.

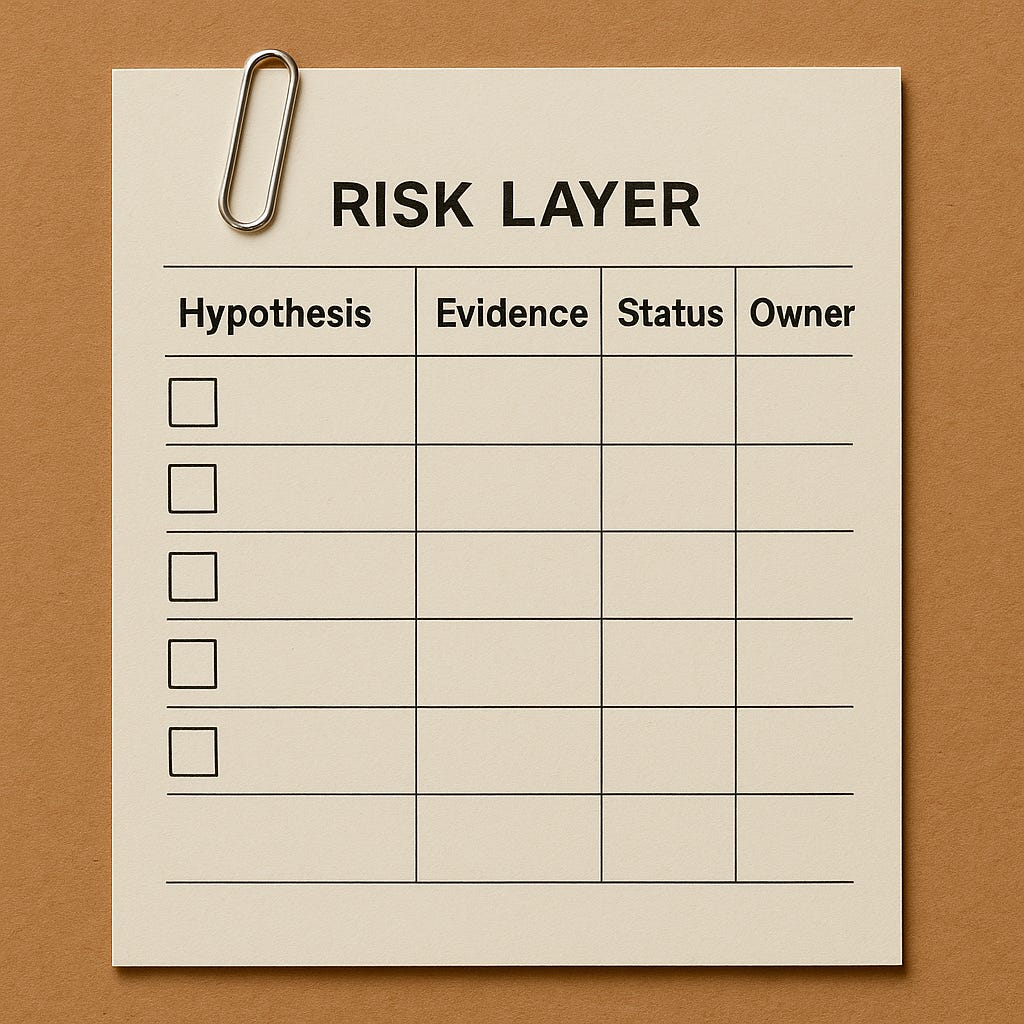

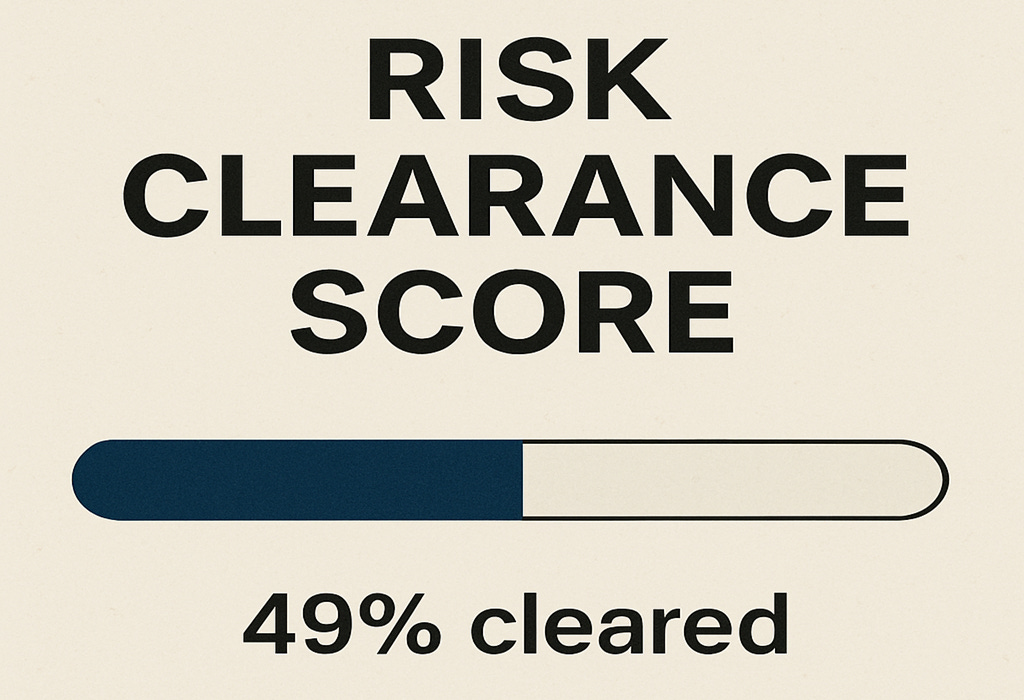

But the goal isn’t to eliminate all uncertainty, rather than to quantify what remains and remove it in the most efficient order possible. That’s where three operating tools come in: the Risk Ledger, the Risk Clearance Score (RCS), and Risk Burn Efficiency (RBE).

The Risk Ledger: Your Living Map of Uncertainty

Think of the Risk Ledger as the startup’s running hypothesis tracker. Each row represents a risk layer, including market adoption, technical feasibility, distribution economics, compliance exposure, and so on. Next to each, you log:

Hypothesis: the assumption you’re testing (e.g., “SMBs will pay $50/month for workflow automation”).

Evidence: what proof you’ve gathered (data, pilot results, retention cohorts).

Status: open, mitigated, or cleared.

Owner: who’s accountable for peeling this layer next.

The ledger turns vague fear into a concrete to-do list. Founders know exactly what to tackle. When reviewed weekly or monthly, it reveals where risk is compounding, and where progress has stalled.

Risk Clearance Score (RCS): Tracking Progress Over Time

Once you’ve mapped the risks, you can quantify how much has been removed. The Risk Clearance Score assigns a weighted percentage to each risk family (People, Product, Market, Economic, Contextual).

At the seed stage for example, your RCS might read “25% cleared”. Team assembled, MVP live, no revenue yet. Six months later, with retention data and LOIs, that could rise to “45% cleared.”

Over time, the RCS becomes a longitudinal measure of credibility. Boards and investors love it because it shows learning growth. And the score helps teams anchor planning around real de-risking, instead of chasing pointless metrics.

Risk Burn Efficiency (RBE): Measuring Risk Removed per Dollar Spent

Capital efficiency is meaningless unless tied to learning. Risk Burn Efficiency measures how much uncertainty each dollar eliminates.

If $500,000 yields a validated product and two proven acquisition channels, your RBE is high. If the same spend produces headcount growth and little insight, it’s low.

A simple formula:

RBE = (Δ Risk Clearance Score ÷ Capital Spent)

Tracking RBE over time helps identify when you’re spending to learn versus spending to maintain. It’s a brutal but liberating metric; it forces clarity on where capital is actually compounding confidence.

Together, these metrics convert a metaphor into an operating dashboard. The onion stops being a story about risk and becomes a scoreboard for learning.

6. How the Onion Explains Valuation and Negotiation

Valuation is more than just a number. It’s a translation of residual risk into price.

Investors don’t value startups on revenue multiples or comparatives until much later. In early stages, they use uncertainty to price a startup.

Understanding this dynamic gives founders a new perspective to approach negotiations differently. Instead of pitching ambition, they anchor conversations in evidence of what’s been de-risked, what remains, and what this round will retire.

A startup that has peeled away team, technical, and market risk commands a higher post-money valuation not because it’s “hot,” but because it’s now safer to fund.

The investor’s perceived discount rate drops, raising the price per share. In practice, valuation becomes a risk-weighted probability curve.

Evidence Over Emotion

Momentum can temporarily distort this logic. During hype cycles, investors conflate speed with safety, assuming fast growth equals low risk. But momentum fades when fundamentals don’t confirm it.

The market eventually reverts to evidence. That is repeatable demand, operational discipline, and defensibility. The founders who thrive through cycles are the ones who keep risk retirement as their core KPI, even when headlines favor expansion.

When you enter a negotiation armed with clear evidence of peeled layers, say, validated retention, signed contracts, or verified margins, you make valuation less subjective.

Because if you’re not proving what’s already been derisked, you end up arguing about what your company might become. And that never works with investors.

How Investors Think in Discounts

Inside every valuation is a hidden discount rate, an investor’s estimate of how much uncertainty remains. The logic is simple:

High residual risk → high discount → lower valuation.

Low residual risk → smaller discount → higher valuation.

Investors use that mental math to balance upside against fragility. If a company still carries tightly coupled risks, say, unproven demand and weak unit economics, they apply a steep discount because a single failure could collapse multiple layers.

But if risks are decoupled and well managed, the investor’s required return shrinks, allowing for higher pricing without breaking their model.

Negotiation as Risk Translation

Great negotiation is all about translating proof into reduced perceived risk. Founders who narrate their progress as “layers peeled and layers next to peel” make investors’ jobs easier. It reframes valuation not as optimism versus skepticism but as mutual accounting. You’re effectively saying, “Here’s how we’ve retired risk faster than peers, and here’s what this round will retire next.”

That’s how the best founders hold leverage in pricing conversations. They quantify learning, not hype.

7. Advanced Insights and Sector Nuances

Not all onions peel the same way. The composition of risk, and the order in which layers must be removed, varies sharply by sector.

A deep-tech founder faces existential technical risk before revenue even enters the picture. A SaaS operator, by contrast, can show early revenue but still fail if customer economics collapse at scale.

Understanding these sector-specific risk signatures helps founders design de-risking roadmaps that match investor expectations and avoid solving the wrong problems first.

Deep Tech: The Physics Layer

In deep tech, technical feasibility and capital intensity dominate the early risk stack. Investors don’t expect product-market fit in the first few years. Realistically, they want to see proof of principle. The first layer to peel is the science itself, defined by functional prototypes, validated performance data, and credible technical leadership.

Because burn rates are front-loaded, founders must demonstrate risk burn efficiency through disciplined experimentation. That could be milestones tied to validation results, instead of headcount or hardware spend.

Once technical risk clears, focus shifts to production scalability and commercialization, often through partnerships with industry incumbents or grant-backed pilots.

In this industry, valuation moves not with users or revenue, but with physics and proof.

SaaS: The Efficiency Engine

For SaaS startups, the biggest risk isn’t building the actual software. It’s repeatability.

Investors look beyond top-line growth to ask whether customer acquisition and retention can scale profitably. Early traction only matters if unit economics improve over time. For example, a CAC payback under 12–18 months, net retention above 100%, and gross margins trending north of 70%.

The de-risking roadmap starts with activation and retention (proving product-market fit), followed by payback compression and churn control (proving scalability).

The “onion” of a SaaS founder is peeled through cohort data and process optimization, turning expansion revenue and customer stickiness into valuation multipliers.

Consumer: The Retention Paradox

Consumer startups often peel layers fast at the top and slow at the core. Early adoption can mask fragility because distribution risk dominates.

Can you keep acquiring users cheaply enough, and will they stay?

The first proof point is distribution velocity (acquisition at a rational CAC), but the deeper layer is retention and habit formation.

Founders de-risk by instrumenting usage behavior early, testing repeat purchase cycles, and building community or brand moats that reduce dependency on paid channels.

When retention stabilizes, valuation shifts from “growth story” to “durable demand engine.” Without that, even viral hits remain uninvestable once momentum fades.

Marketplaces: The Liquidity Trap

Marketplaces live and die by liquidity risk, which is the ability to balance supply and demand density. At launch, every other risk depends on solving this one. Founders de-risk by proving transaction velocity within a niche market before chasing scale.

Key signals include reducing time-to-match, maintaining healthy take rates, and preventing disintermediation. Once liquidity deepens, investors turn to operational risk.

“Can the marketplace sustain trust, enforce quality, and expand adjacently without collapsing network value?“

Successful marketplace founders treat liquidity as their primary KPI until network effects compound.

Fintech and RegTech: The Compliance Moat

In fintech and regulatory technology, external risk defines valuation far more than growth metrics.

Founders de-risk by building credibility infrastructure. That means obtaining licenses, aligning with regulatory sandboxes, and demonstrating robust KYC/AML systems.

Investors look for a compliance-first posture because unmitigated legal risk can nullify every other layer. Once that base is stable, product and economic layers peel more predictably.

The best fintech founders view regulation as a moat, while others view it as a constraint. Each certification peeled becomes a barrier competitors can’t cross quickly.

Ultimately, every sector prioritizes different layers, but the logic stays constant. capital should buy the next few proofs that matter most to your category.

8. Putting It All Together: Building a Risk-Driven Company

Every enduring startup is, at its core, a risk retirement machine. Products, growth loops, and revenue models are simply the visible outcomes of a deeper process. The process of systematically converting uncertainty into knowledge.

When founders internalize that idea, strategy becomes clearer, fundraising becomes easier, and execution becomes far more deliberate.

Value creation is uncertainty reduction

Each milestone, whether it’s shipping an MVP, closing a customer, or clearing a regulatory hurdle, represents one less unknown in the company’s story. Investors don’t reward potential in isolation; they reward proof that potential is being realized with precision. The faster a team converts assumptions into evidence, the faster valuation compounds.

Fundraising is risk translation into capital

Every round exists to peel the next two or three layers of the onion. When founders pitch using this lens; here’s what we’ve retired, here’s what this capital will retire next; they move from storytelling to accountability. Capital stops being a gamble and becomes a shared plan for de-risking the business.

Execution is structured learning

The best founders don’t chase certainty; they engineer it. They treat each quarter as a 90-day sprint of risk tests; prioritizing what matters most, measuring results, and updating their ledger. Progress becomes visible through shrinking unknowns.

In the end, every successful company follows the same trajectory. You start as a bundle of unproven layers, apply focused heat through execution, and rise in value as each layer burns away. ‘

The Onion Theory of Risk is the blueprint for building startups that learn faster, waste less, and scale on evidence instead of assumptions.