When Did Venture Capital Stop Being Venture?

Inside the story of how Venture Capital has turned into Consensus Capital.

Has Venture Capital Become a Consensus Machine?

Try to find something that screams conviction louder than early stage venture capital. VC was always seen as fuel for the bold, the visionaries. It built its identity on backing the improbable before they became inevitable.

But that image no longer matches the institution itself. Today’s capital doesn’t hunt in the wild, rather it follows heat maps.

Indeed, the biggest players operate differently now. They move in packs, they spread risk, and lock in access through syndicates. Taking on less risk is more important than achieving outsized returns.

As the industry scaled, it reorganized around a different center of gravity, one that prizes access, speed, and size over original insight. And what we’re left with isn’t just a new funding model, but a whole new industry, built on a completely different scope of logic.

In a market driven by consensus, first impressions matter earlier than ever.

Founders are expected to look fundable before the product is finished. The website has become infrastructure, not marketing.

That’s why I’m so happy to share that I’ve secured one full year of Framer Pro free (worth $360) for The VC Corner audience.

It lets early-stage founders launch a serious, production-ready site in hours, without a dev team, and scale it later with CMS, analytics, and localization.

Table of Contents

1. The New Game: From Venture Capital to Consensus Capital

2. The Myth of the Contrarian: Why Early-Stage Markets Are Becoming Efficient

3. Syndication: The Quiet Data Behind the Herd

4. The Economics of Scale: When Size Kills Alpha

5. Important Takeaways for Founders

6. Why This Shift Matters for LPs Too

7. The Future of Alpha: What Comes After Consensus

8. Redefining Venture Capital, Honestly

1. The New Game: From Venture Capital to Consensus Capital

For most of its history, venture capital meant small partnerships making high-conviction bets on early-stage startups. Funds were lean, check sizes were modest, and partners staked careers on single deals.

But that structure broke apart in the past few years as venture firms grew into financial institutions. Many now operate as RIAs, managing billions across multi-asset portfolios that include late-stage equity, public stocks, crypto, and secondaries.

They’ve essentially crossed the line from high-risk speculation into structured allocation.

And thus, a different model took shape. We saw the rise of “mega-funds” that move like institutions. They spread capital across larger rounds, optimize for deployment velocity, and build brand-led ecosystems around repeatable outcomes.

Apparently, there’s no room for artisanal, creative, bold investing when the fund size hits $20 billion.

Make no mistake. This transition wasn’t arbitrary. As years of near-zero interest rates flooded the system with capital, LPs began seeking scalable, tech-enabled returns, but with institutional guardrails.

Consensus capital emerged from that demand. Venture adapted accordingly. Firms expanded teams, layered on platforms, and institutionalized their strategies.

But this wasn’t a corruption of venture capital, rather an institutionalization. Not better, not worse. Just structurally different.

2. The Myth of the Contrarian: Why Early-Stage Markets Are Becoming Efficient

Andreessen Horowitz partner Martin Casado sparked debate when he pointed out that early-stage startups aren’t as contrarian a bet as many VCs claim.

Venture capital has always mythologized the maverick, the one who bets before others even notice. But in today’s market, that story doesn’t hold the same weight. Casado wasn’t dismissing risk-taking, instead, he was observing how often the best companies are already priced accordingly.

Great startups tend to reveal themselves early, and the signals are hard to miss.

In highly networked environments, alpha doesn’t always live on the edges. It often clusters in plain sight. It clasters around traction, credentials, and sharp storytelling.

Behavioral economists like Kahneman have long noted how strong signals compress independent judgment. George Soros called this a reflexivity. The theory that once a belief enters the market, every additional belief reinforces it.

Startup investing is no different. Follow-on dollars, valuation markups, and co-investor activity all amplify the same signals until few investors want to diverge.

Consensus capital is a survival mechanism, and no longer a shortcut. When you’re trying to optimize for downstream capital or round momentum, being early isn’t always rewarded. Being legible is.

Looking too strange, too soon, can stall your deal. So founders will polish their pitch decks to match the market’s priors, and investors lean into what the market already approves. In that feedback loop, the myth of the contrarian starts to fade, and a new, consensus-shaped alpha takes its place.

3. Syndication: The Real Data Behind the Herd

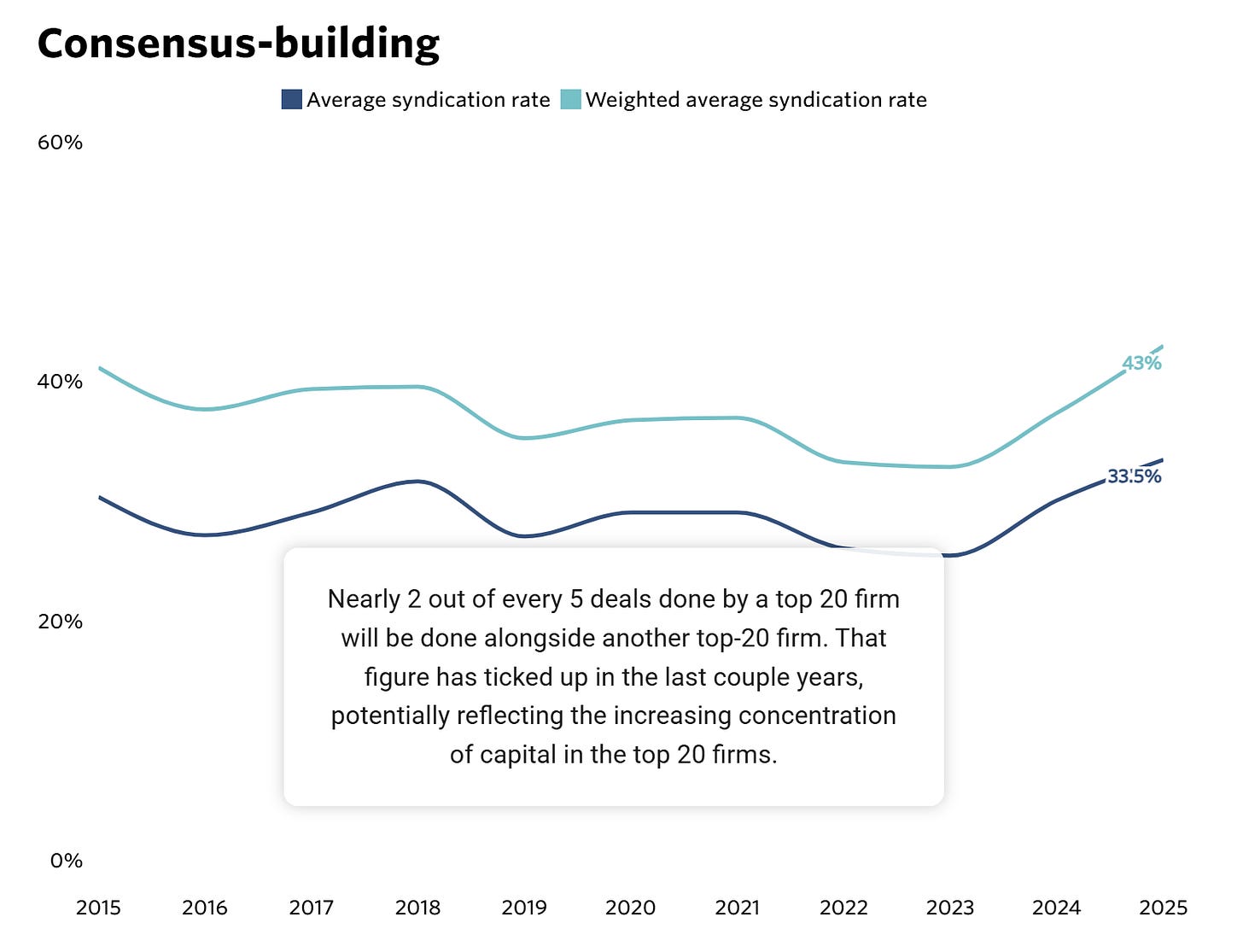

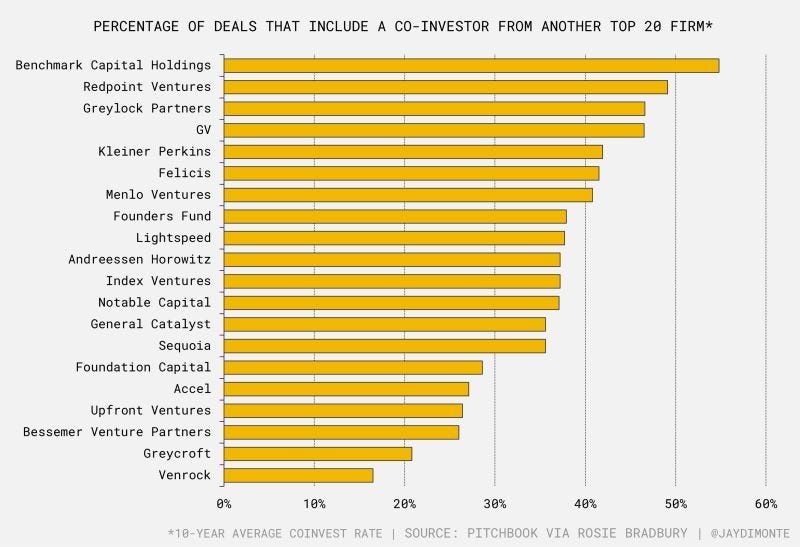

Venture capital loves the mythology of independence. Every firm pitches its edge, its proprietary pipeline, its unique lens on the future. But the actual behavior tells a quieter, more collective story. According to PitchBook data compiled by Rosie Bradbury, roughly 40% of all deals led by top-20 firms are co-invested with at least one other top-20 firm.

In practice, that means the same names show up together on cap tables over and over, either by co-leading, following, or simply joining the same few rounds.

This isn’t a coincidence. It’s coordination. Syndication helps top firms spread risk, validate pricing, and maintain access to follow-on opportunities. It also plays well with LPs, who often prefer to see familiar logos on the deal.

In an environment where downstream capital is king, signaling matters as much as conviction, and nothing signals like a group of brand-name VCs moving together.

That’s not a knock toward top VCs however. For funds managing billions, this kind of behavior is indeed rational. Deploying large checks into large rounds requires confidence not just in the company, but in the syndicate itself. It’s safer to follow known co-investors than to chase a solo thesis that might leave you stranded later.

But it does make you think. If even firms like Benchmark and Redpoint that are historically seen as high-conviction and “lead-first” investors, prefer to operate in the comfort of consensus, what does that say about the industry’s actual structure of incentives?

The herd, it turns out, isn’t always driven by fear. Sometimes, it’s just good business.

4. The Economics of Scale: When Size Kills Alpha

As a fund grows in size, the rules of the game change with it too. The moment a firm crosses into multi-billion territory, its constraints become mechanical.

A $20B fund can’t afford to make dozens of $1–2 million bets and wait for one to explode. It needs to move volume through large checks, large rounds, and ideally, large outcomes that will return money to investors (LPs).

At that scale, strategy tilts away from discovery and toward allocation. Many mega-funds now behave more like structured asset managers than classic venture firms. They track category leaders, lean on co-investor syndicates, and pursue exposure to themes that are already de-risked.

But don’t confuse this with laziness. It’s more of an adjustment to the sheer pressure of capital deployment.

Financial theory gives us the language for what’s happening here. That means diminishing marginal returns, liquidity constraints, and beta correlation. Every extra dollar in a large fund delivers less differentiated return. Because the more you grow, the more your portfolio drifts toward systemic exposure. Alpha thins out because the moves become predictable and often crowded.

This tradeoff is palatable for a fund’s LPs. Institutions aren’t chasing unicorns; they’re managing risk-adjusted returns across portfolios. A consistent 2.5x from a scaled, brand-name firm looks more attractive than a scattershot of 5x-or-zero outcomes.

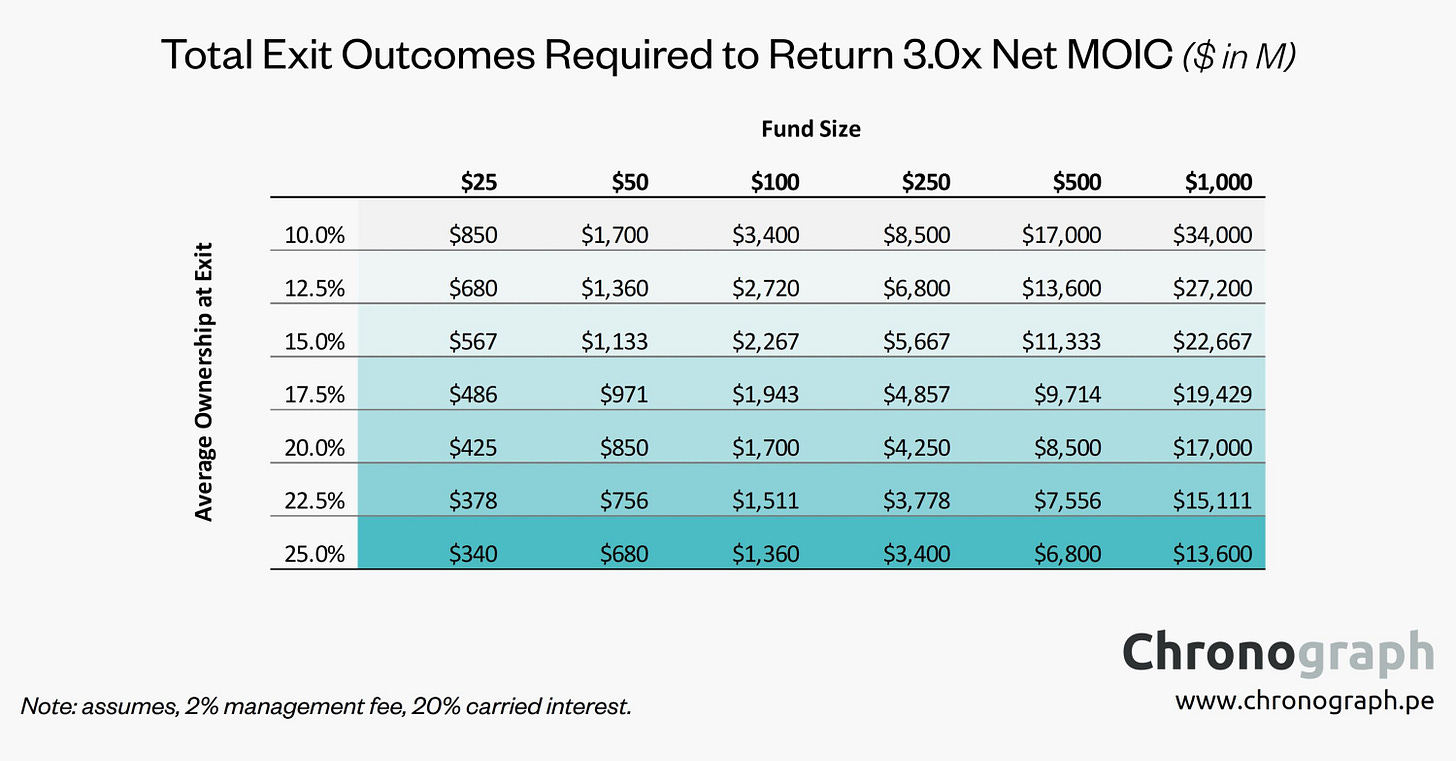

Consider this scenario. Let’s take a $100M fund with ~20% average ownership. It needs roughly $1.7B in aggregate exit value to hit a 3x net return, while a $1B fund at similar ownership needs about $17B.

When your hurdle changes from “find one or two $1–2B outcomes” to “manufacture multiple $10B-plus winners,” it becomes rational to pile into the same de-risked, consensus names and avoid anything that doesn’t obviously clear that bar.

So ultimately, predictability feels like safety, especially in down cycles. That psychology rewards scaled strategies even as it flattens upside.

This is the quiet tension at the heart of today’s venture capital landscape. The very firms best positioned to shape the market are often the ones least able to break from it.

5. Important Takeaways for Founders

The capital stack has bifurcated. If you’re a founder with the right signals, whether that is a Stanford hoodie, YC badge, or ex-FANG stamp, then you’re already on the radar. Funds will find you before you finish your deck. But that access comes with trade-offs.

Competitive rounds drive valuations up fast, and the price is ownership. It’s not unusual to lose more than half your company by Series B, especially when mega-funds pile in early. You’ll close the round, but you may be working for the cap table.

On the other end of the spectrum, if you’re building outside the pattern, in the wrong city, with no angels in your corner, then raising capital can feel like screaming into the void. But this end of the market isn’t dead. It’s where real venture capital still operates, with smaller funds writing checks based on insight, without relying on the consensus.

The dollars are harder to access, but the alignment often runs deeper. These firms aren’t looking for plain exposure. These firms are looking for high conviction bets, and they’re willing to go against the grain, in order to be early.

The paradox is that founders now have to build a non-consensus product but deliver a consensus pitch. Yes, the product does need some edge; something new, strange, unfair. But the story must be legible enough to pass through the filters of fund partners, Investment Committees, and LP updates.

Most VCs don’t invest in ideas, but in narratives that sound like other winners. Knowing how to translate vision into the language of consensus is survival.

So how should founders navigate this? If you’re working on a fast-follow in a hot market, go where the capital is most efficient. Stack the logos, maximize the round, build to a milestone, and protect optionality.

But if you’re building something weird, slow, or culturally misaligned with the consensus crowd, stay close to smaller, high-conviction funds. They won’t outbid each other, but they won’t try to rewrite your roadmap either.

None of this is new. What’s changed is how visible the divergence has become. In 2025, founders are raising in a system that looks unified from the outside, but underneath, it’s two markets, two sets of rules, and two different definitions of conviction.

Case Snapshot: Notion’s Slow Start, Strategic Control

When Notion launched in 2013, few investors understood what it was. Too broad. Too design-led. Too early for the market. They struggled to raise a proper seed and actually rebooted in 2016 with just $150K in the bank and no full-time team.

So instead of chasing consensus, the Notion team focused on product depth and shipping for years. By the time they raised again in 2020, they were profitable, global, and exploding in adoption.

They raised $50M at a $2B valuation. And that round was just a formality. Investors weren’t betting on a risky unknown; they were buying access to something already working. Notion didn’t optimize for logos or dilution. They optimized for control. And because they had waited, they could set the terms.

The lesson wasn’t about stealth or scarcity. It was about knowing when to step into consensus and when to stay outside it. For founders building real products, capital isn’t just fuel. It’s also timing, leverage, and positioning. Notion didn’t look back.

6. Why This Shift Matters for LPs Too

Founders feel the ripple effects. GPs see the market rewire beneath them, forcing them to adapt. But many of the most consequential forces affecting how the market changes from the ground begins with the limited partners.

LPs aren’t betting on startups. They’re betting on fund managers to deliver risk-adjusted returns across 10-year horizons. In that calculus, consistency matters more than outliers.

This preference is what designs fund strategy, especially at scale. It’s why many institutions now allocate to large, branded venture firms the same way they do to public equity or growth funds. The more a fund looks and behaves like a portfolio optimizer, the easier it is to justify on an investment committee slide.

This is how consensus capital becomes self-reinforcing. LPs want dependable exposure to innovation. GPs want predictable downstream capital. Founders optimize for the language that gets them through both gates.

In that loop, the system doesn’t chase risk, it absorbs it, then smooths it.

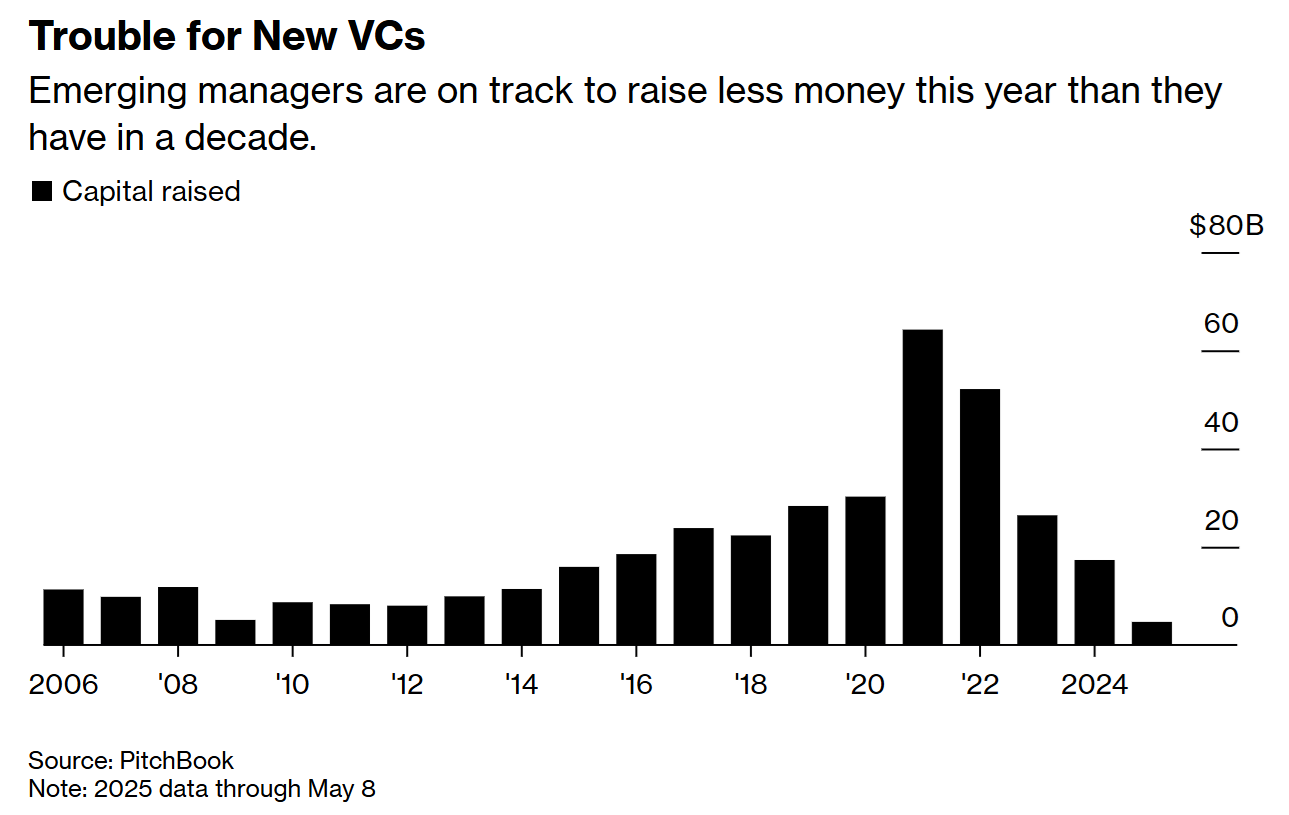

Meanwhile, smaller funds that are still trying to practice conviction-driven venture capital, are raising into headwinds. Even with strong distributions (DPI) and realized alpha, many of them struggle to raise follow-on vehicles unless they anchor to a marquee lead or adopt hybrid strategies. And when capital formation tilts toward scale, innovation financing gets narrower.

The result is that fewer ideas get funded and more bets look the same.

This isn’t a flaw in the system. It’s an expression of its incentives. But ignoring the LP layer means misunderstanding where risk tolerance really begins, and where it really ends.

7. The Future of Alpha: What Comes After Consensus

In every cycle, consensus eventually eats its own edge. The venture market today may feel efficient at the top, but history suggests new inefficiencies are already forming, just not where the capital is currently flowing.

Frontier tech will likely reopen alpha pathways first. AI agents, synthetic biology platforms, dual-use defense systems, and climate infrastructure aren’t just hard to build; they’re also hard to price.

These sectors don’t yet follow the pattern-matching logic that drives today’s consensus capital rounds. The founders don’t always speak in pitch-perfect metaphors. The TAMs are ambiguous. And the investor theses haven’t yet turned into actionable playbooks.

For example, biotech platforms are capital-intensive, slow to monetize, and deeply technical. But they unlock new infrastructure layers, spanning pharma, materials, agriculture, where traditional venture timelines and metrics don’t easily apply. The alpha, when it comes, arrives in nonlinear bursts.

Geography and founder identity offer another leak in the consensus machine. Yes, capital still clusters around a handful of zip codes and social networks. But arbitrage exists, sometimes in Nairobi, sometimes in Omaha, sometimes in a Telegram channel where the cap table doesn’t look like the Stanford computer science graduating class. The next breakout founder may not be invisible, but they’ll be unreadable to the current filters.

Startup Location Strategy in 2025: Does It Still Matter Where You Build?

There was a time your startup’s address was your first hiring decision. When being in Silicon Valley or London meant that you were serious, while anywhere else meant you were either brave or foolish.

Capital structure itself is also mutating. Rolling funds, operator-led syndicates, tokenized special purpose vehicles (SPVs), and revenue-share agreements are altering how early bets are made.

Although these models don’t always show up on PitchBook and aren’t easy to benchmark, they create space for a different kind of investor, one who isn’t chasing exposure, but experimenting with entry.

But let’s zoom out. What we find is that underneath it all is something older than venture math, and that is human conformity. After all, humans are wired to seek signals, to cluster around safety, to act like the last fund that got the last mark-up.

But that same cycle of imitation eventually creates blind spots. The moment a market looks over-explored is often the moment something mispriced slips through.

Alpha doesn’t vanish. It just moves somewhere else. And for those still willing to look, the next edge won’t come from a louder pitch deck, but from listening where no one else is paying attention.

8. Redefining Venture Capital, Honestly

The ecosystem doesn’t need more mythology. What it needs is sharper language. We call too many things “venture capital” that behave nothing like the original version. It may sound like criticism, but there really is a mismatch in how we describe the industry.

Let’s reframe. Venture capital is conviction at the edge. That means early risks, unclear outcomes, and partners who make a few bold calls across an entire fund cycle.

Consensus capital is a different game. It operates at scale, across multiple stages, and optimizes for brand, signaling, and repeatable exposure.

Both are valid. But lumping them together blurs the lens. It distorts how we evaluate performance, how funds are benchmarked, and how founders navigate the fundraising process. Without distinction, we lose resolution.

What we’re seeing today isn’t a breakdown of venture, but a branching event. One arm matured into infrastructure. The other stayed messy, strange, and thesis-driven. Seeing that clearly is the first step toward making better decisions as a builder or investor.

No one benefits from nostalgia. What matters is understanding where the real edge lives now, and choosing your own position with clarity.

Very well articulated and insightful. One of the most eye opening books on the subject is “Pattern Breakers” by Mike Maples Jr. One thing that concerns me is that the second order effect of this may actually be less good innovation for the US innovation ecosystem. A bit like killing the goose that laid the golden eggs.

Thank you, Ruben, for another thought provoking piece. There is one thing that you could do better.

I don’t know who your target audience is, but in order to understand your piece and (dis)agree with it, you MUST define terms.

In my experience:

1. Even many experts differ in their understanding of terms.

2. Most startup founders have little to NO clue when it comes to business disciplines be it strategy, marketing, operations, or finance.

So, how do you define, or what definition do you use for VC, please?

What is RIA?

…

Again, thank you for the good work you do.