Everything You Knew About VC Fund Math Is Wrong

Before the hype, before the founders, before the first check , it’s the math that decides whether a venture fund will work.

What Actually Decides a Fund’s Success

Most venture capital funds fail not because they missed great companies, but because most of the time, they get the venture fund math all wrong.

Before the General Partner (GP) wires the first check, the outcome is already baked into the model. That means ownership targets, fund size, VC reserves strategy, and how much capital gets recycled later.

Those choices are what ultimately decide whether the fund has any mathematical chance of returning a 3× net to its Limited Partners (LPs) or whether it’s doomed to stall below waterline before deployment is even done.

Venture capital investing isn’t random. Most of that arithmetic still lives inside spreadsheets…

Brought to you by ClearFactr

Most startup risk doesn’t come from the product

The same math that decides fund outcomes also decides startup outcomes.

Runway, dilution, burn, pricing.

All of it lives in spreadsheets that quietly shape decisions long before reality hits.

ClearFactr makes those models auditable, governed, and resilient, while keeping the spreadsheet UI founders already trust.

When models drive decisions, outcomes follow.

Think of it as arithmetic wrapped in storytelling. The illusion of “access” or “deal flow” only lasts until the numbers come due. A $50 million seed fund owning 10-12% in thirty companies can plausibly 5× if one or two go the distance. A $500 million fund with the same pattern can’t, as the exits required to make the math work simply don’t exist at that scale.

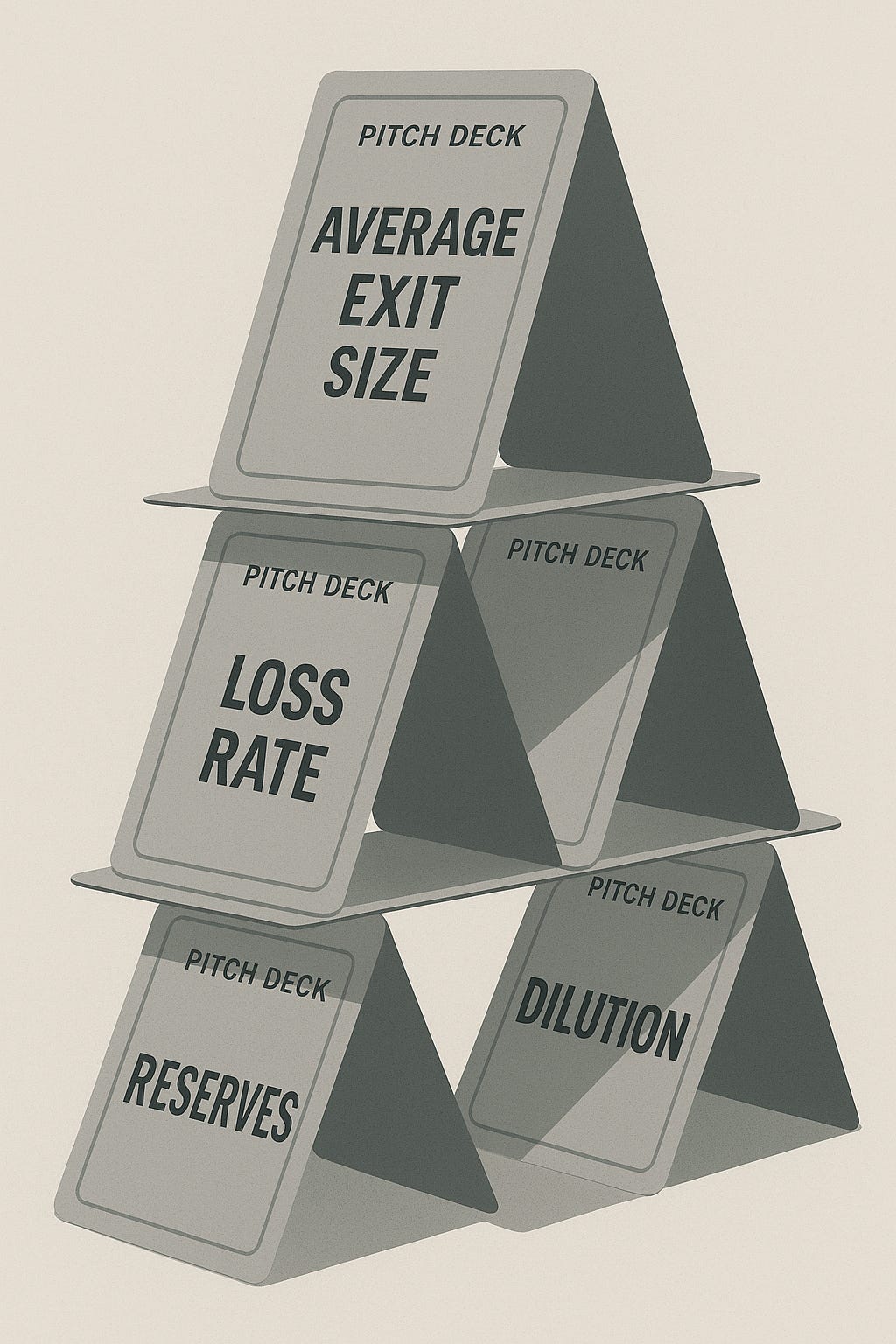

The uncomfortable truth is that most funds fail by design. Their portfolio construction looks impressive in a deck but collapses under real outcome distributions. Every assumption they make, such as average exit size, loss rate, dilution, reserves only compounds the error. Miss on two of them and you’re chasing ghosts by Fund III.

That’s why we’ll talk about those errors here. We’ll break down why ownership and outliers are the only numbers that matter, how reserves bring down multiples, why recycling venture capital is the most underused weapon in the toolkit, and why emerging managers often outstrip the mega-funds that raised ten times more.

Table of Contents

1. Why Most Funds Are Built on Faulty Math

2. Ownership and Outliers: The Only Two Numbers That Matter

3. Reserves: The Mirage That Drags Down Multiples

4. Recycling: The Quiet Weapon Nobody Uses Enough

5. Fund Size: Why Smaller Funds Punch Above Their Weight

6. The Fund Math Playbook (What Actually Works)

7. Respect the Math, Or the Math Will Humble You

1. Why Most Funds Are Built on Faulty Math

“Good deck, terrible model.” That’s how many GPs raise capital using glossy slides, confident projections, but no survival guarantee once you run the numbers. The sad truth is that the trailers, brand names, and deal flow pictures, none of that matters if the underlying fund math is flawed.

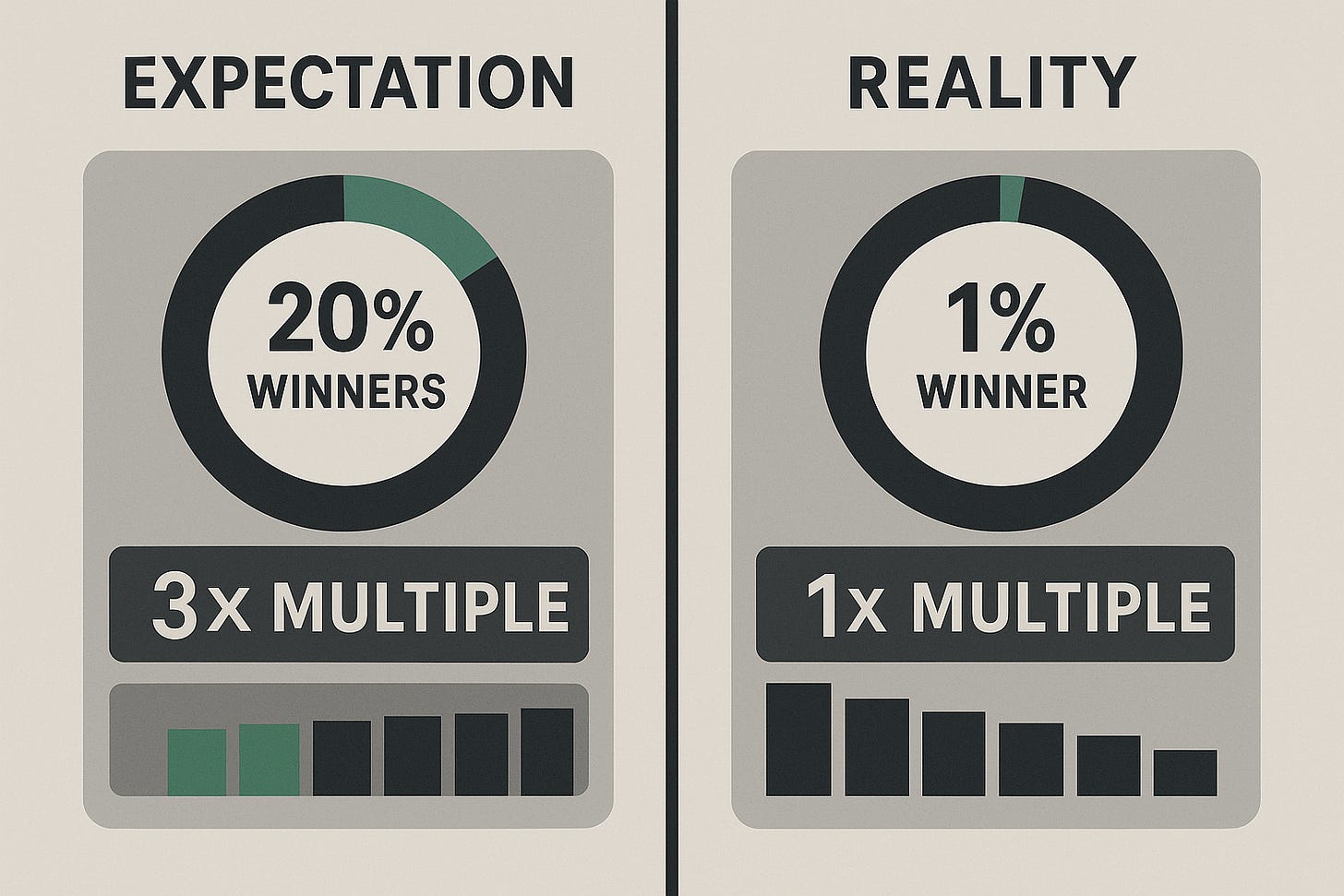

The Illusion vs. the Reality

GPs often pitch with scenarios like: “If we back 30 companies and hit 3 unicorns, we’ll return 5×”. But these projections typically assume perfect execution. They assume perfect conditions like low dilution, moderate failure rates, and generous follow-on deployments.

But what about risk stacking? That’s what’s missing. The reality of dilution, reserves allocation, and outcome dispersion.

The fundraising deck is all about optimism, but the model is about math.

If your portfolio construction assumes 20% failures, 3× multiples on winners, and you forget that reserves dilute the base invested capital, you’ve already built in a loss before picking one company.

Benchmark Dispersion: Median is Closer to Failure

According to data, most VC funds don’t “fail” in the sense of returning zero, they fail by underperforming expectations. The median fund often returns just ~1.5× capital over its life, meaning barely 0.5× above break-even after fees. And that, for many LPs, is failure. Some funds do generate 3×-5×+ returns, but that’s reserved for the outliers, not the baseline.

Cambridge Associates data shows the volatility even in benchmark indices. Their US Venture Capital Index (net of fees) returned –3.4% in 2023.

In 2024, that same index rebounded to 6.2% annualized return, but that is just the index, not individual fund multiples. The swings tell you that most vintages will produce mediocre or negative annual returns before a few winners skew the curve upward.

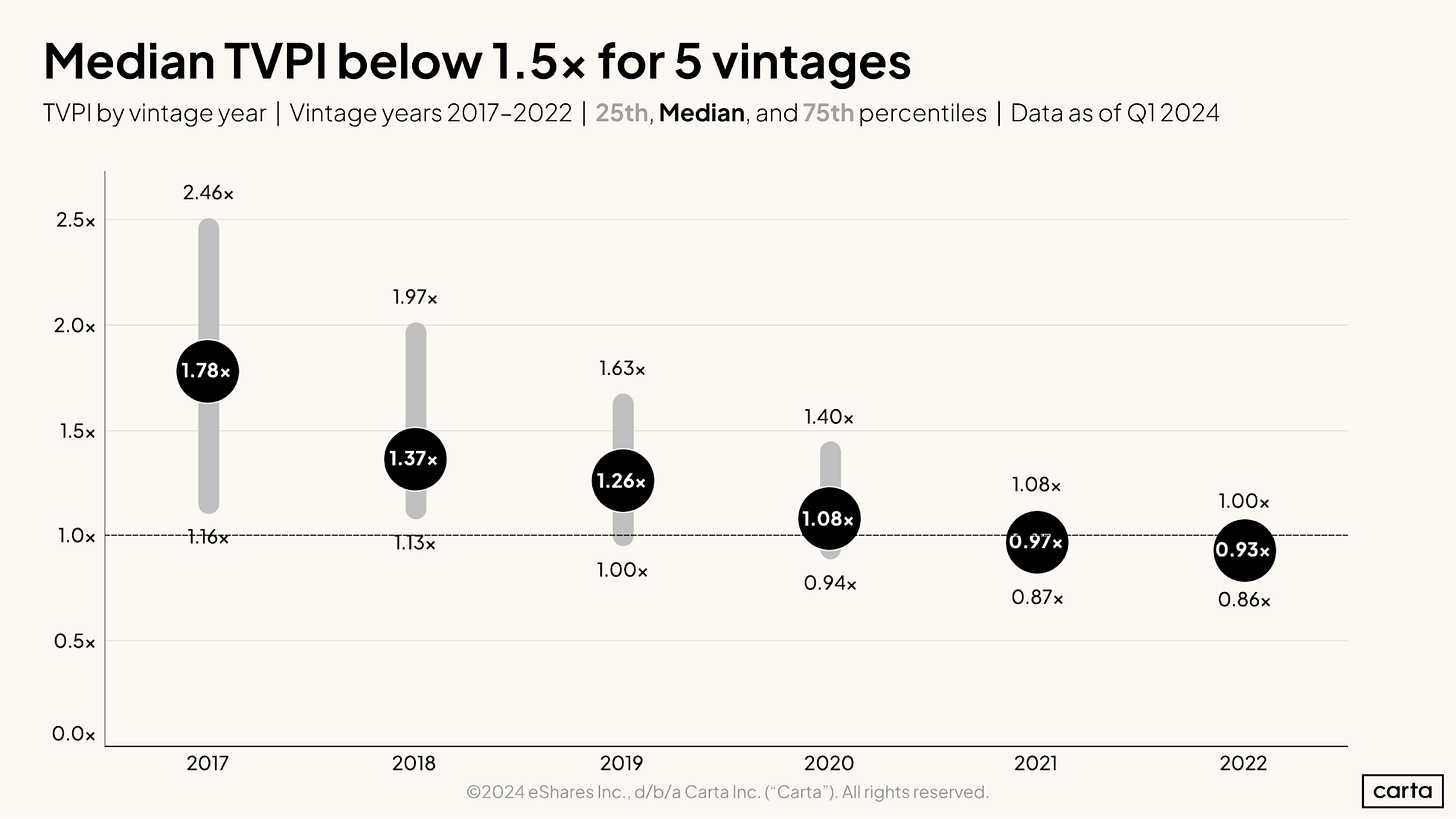

According to Carta’s VC Fund Performance Report, across ~1,800 funds from vintages 2017-2022, the median TVPI (Total Value to Paid-In Capital) is often under 1.5× during the middle years of a fund’s life. That shows that most funds are actually just getting by.

And when you break out sectors, PitchBook data shows the median multiple on invested capital for pharma deals by specialist VCs was just 1.5×, compared to 1.3× by generalist firms. Granted, that’s sector-level, but it illustrates how “good sectors” don’t magically produce stellar fund-level math unless ownership, dilution, and follow-ons are structured tightly.

Why Median Is a Red Flag

If the median is ~1.5×, that means more than half of all funds land below that multiple. That’s not “normal returns,” but actually underperformance for many LPs after deducting fees.

The asymmetry is severe, with the top 10-20% of funds generating 3×, 5×, or even 10×+, dragging the index upward, masking how many funds are actually floundering.

In effect, a fundraising model built on optimistic assumptions is a house of cards.

2. Ownership and Outliers: The Only Two Numbers That Matter

At the end of the day, every dollar in your fund either multiplies or it doesn’t. And almost all of the upside comes from just a few bets. So you don’t win by hitting many doubles, you win by getting real ownership in real outliers.

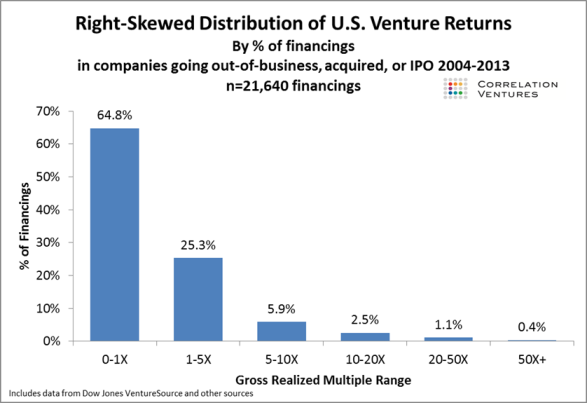

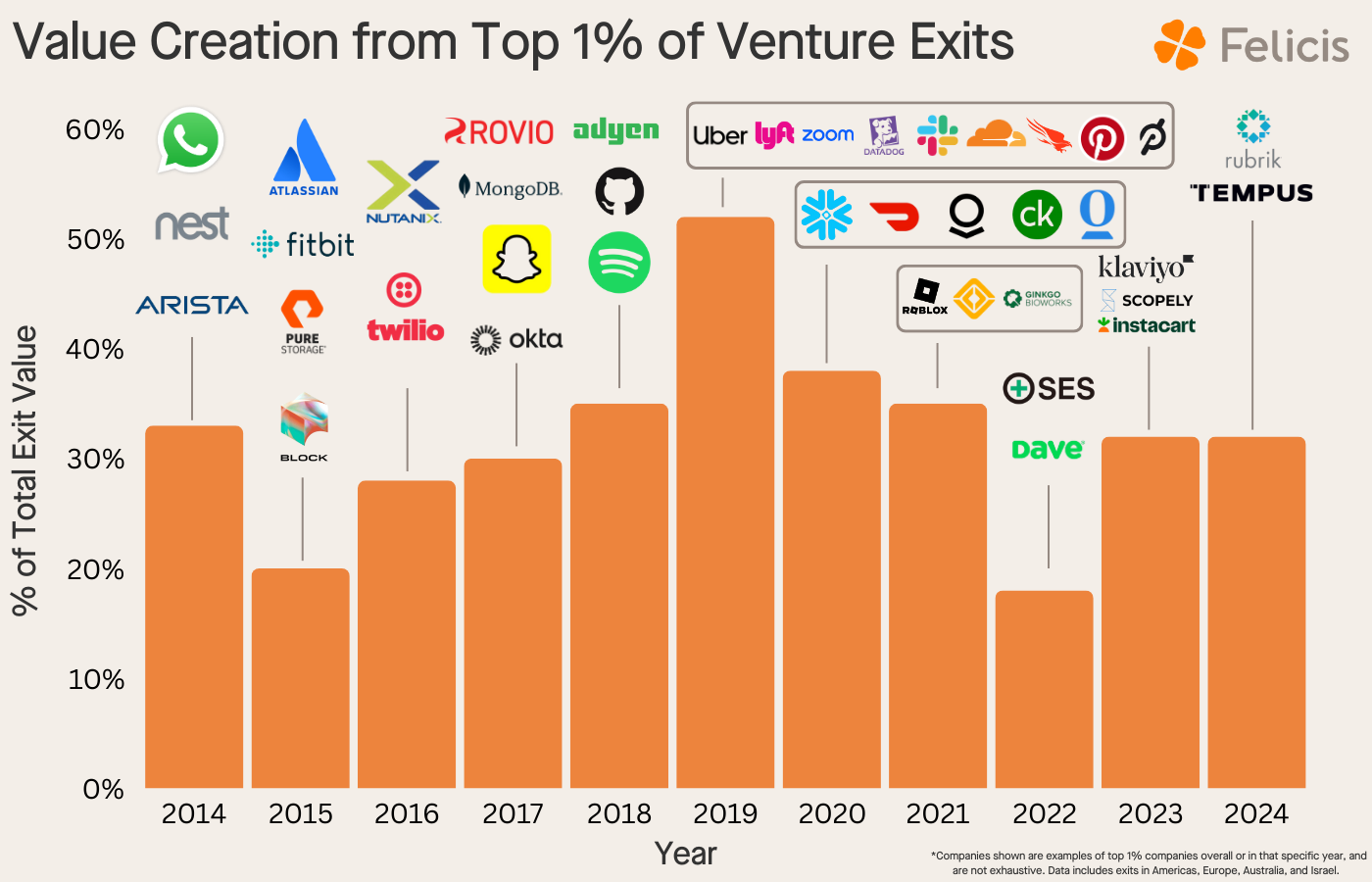

Outliers: The Skew Is Brutal

In their analysis of ~21,000 financings, Correlation Ventures found that about 65% of investments fail to return capital (i.e. go to zero or below 1×), and fewer than 4% deliver 10×+ multiples.

Meanwhile, Sapphire Ventures (via Fund Math for Dummies) gives us a rule of thumb for well-performing funds: in a fund that ends up being 5× or greater, the top company averaged ~90×, the second-best ~25×, and the rest of the portfolio averaged ~1× (i.e. break-even).

So ultimately, you don’t need many winners, you just need one or two that dominate. In many top-tier funds, the #1 exit often contributes more than half of the value.

One Unicorn Can Save the Fund

Imagine a $35 million seed fund making 30 investments. Suppose 29 of those fail (return 0), and one becomes a $5 billion exit.

Now let’s say the GP originally acquires ~5% ownership in that company, and after dilution ends up with ~3%. That 3% of $5B = $150 million, giving the fund ~4.3× gross multiple (before fees/carry).

Now add modest outcomes (one or two small winners) or reserve upside, and voila, the fund has a shot at 5×+ net.

But if you remove that one big exit; if nothing hits that scale, the fund likely returns <1× (i.e. loses money), because the other 29 bets are zeros.

Missing the unicorn means the fund fails; nailing it means you can carry the rest of the dead weight.

Ownership: The Invisible Lever

You can pick the perfect outlier, but if you don’t own enough of it, your fund still fails.

Entry Price and Dilution: The Silent Killers

Here’s a simplified illustration:

Suppose your fund invests in three outliers:

$2B exit

$1B exit

$500M exit

Scenario A: You entered at $10M post-money, got ~10% ownership, diluted to ~5%. The fund’s gross multiple might be ~5×.

Scenario B: You entered at $20M post-money, yielding ~5% ownership (diluted to ~2.5%). The same exits now deliver ~2.5×.

Scenario C: You entered at $40M post-money, getting ~2.5%, diluted to ~1.25%. The same exits deliver ~1.25×.

The takeaway here is that valuation discipline is non-negotiable. A “hot” deal at $40M might feel good for the press, but mathematically it could be your undoing.

Why Hot Deals Hurt Small Funds

When multi-stage or crossover funds rush into early-stage deals at high valuations, they compress ownership for early investors. In those rounds, an emerging manager might only get 2-3%, diluted to ~1%. Even if the company becomes a $2B exit, 1% of $2B is $20M; insufficient to move a $50M fund needle meaningfully after fees and carry.

Founders often mistake high valuation checks for validation. But for small funds, the real validation is whether ownership math still works.

3. Reserves: The Mirage That Drags Down Multiples

Every GP loves to say, “we’ll double down on our winners.” It’s one of those lines that sounds sharp in a pitch deck but rarely survives contact with real fund math. LPs hear it so often they’ve learned to translate it automatically to “we’ll dilute our returns while feeling good about it.”

Because the truth is that a reserve strategy only works when it’s concentrated ruthlessly in the very best names.

Laura Thompson of Sapphire Ventures demonstrated in her landmark analysis, “The Dirty Secret: Venture Reserves Are Not Always a Good Thing.”

Concentrated in Winners (Good, but Rare)

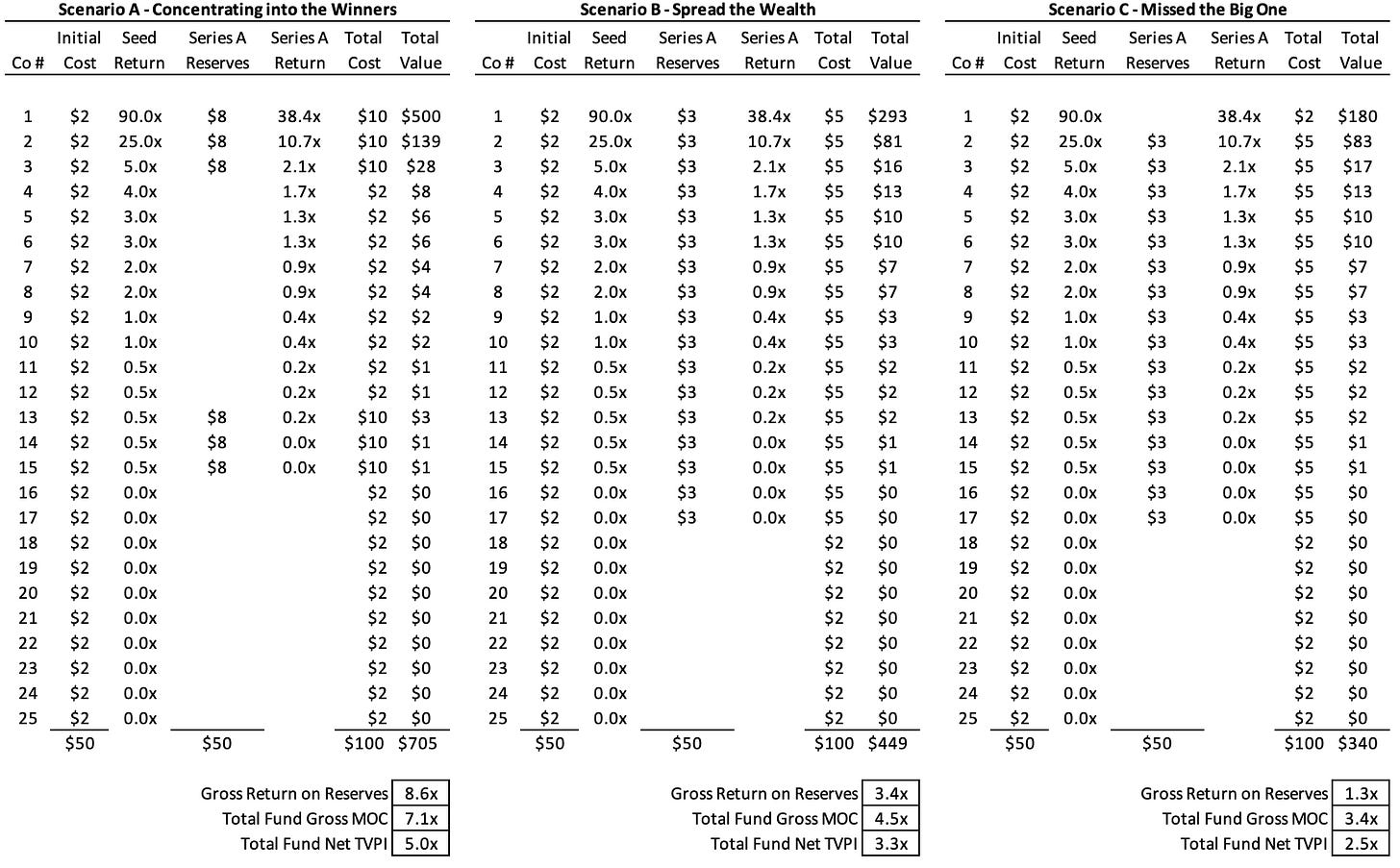

Thompson modeled a $50 million seed fund investing in 25 companies. When reserves were focused on the few clear breakouts, the outcome improved modestly: the gross multiple rose from 5.5× to 7.1× and the net to LPs from 4.0× to around 5.0×.

A solid uplift, but hardly the salvation many decks promise. To pull this off, the GP must identify future outliers early and have the conviction to load capital there; a razor-edge skill few possess consistently.

Pro-Rata Across the Board (Common, and Costly)

In Thompson’s second scenario, the GP followed on pro-rata rights in every company that raised a Series A. That’s the “we back all our founders” approach investors love to tout.

But the math turned punishing as the gross multiple slipped to ~4.5×, and LP net returns sank to 3.3×. Most of those extra dollars ended up reinforcing mediocrity by doubling positions in companies destined to stall or fold.

The result is capital being spread thinner, outcomes diluted, and the fund’s true winners masked by average ones.

Missing the Winner (Disastrous, but Frequent)

The third case is the nightmare every LP can name: the GP follows on broadly but somehow misses the eventual breakout. Maybe they lacked conviction or dry powder. Either way, the fund’s gross plunges to ~3.4× and net to ~2.5×.

But the kicker is that even as LPs’ multiples fall, the GP’s carry dollars can still rise, because more capital was deployed.

Thompson called it the “misalignment nobody likes to talk about.” LPs fund more work, get smaller returns, and the manager still wins on paper.

The Real Lesson

Reserves aren’t evil; they’re just misunderstood. They create leverage only when paired with exceptional selection skill and discipline. Without that, they quietly turn into ballast; swelling AUM, inflating management fees, and sinking LP outcomes.

That’s why experienced LPs tense up when they hear, “we’ll just follow our best.” History shows that most GPs don’t. They over-reserve for comfort, under-invest in conviction, and call it prudence, while in reality it’s decay.

4. Recycling: The Quiet Weapon Nobody Uses Enough

If reserves are the illusion that dilutes returns, recycling venture capital is the antidote to that. It’s the most mechanical yet most underused advantage in the fund playbook, a simple idea that compounds quietly over time.

Recycling means when a fund gets early liquidity, either through a quick M&A, secondary market sale, or partial exit, and instead of distributing that cash immediately to LPs, the GP redeploys it into new or existing portfolio companies.

Now many mistake it for greed, but GPs call it efficiency. Redeploying those dollars reduces fee drag and keeps more capital working for longer, tightening the gap between a fund’s gross and net multiple.

Laura Thompson calls recycling one of the least appreciated levers in venture fund math.

In her analysis, a $100 million fund that invests only once, no recycling, might post a 3× gross return that nets out to barely 2.1× after fees and carry. But if that same fund reinvests a modest amount of early proceeds, the net multiple rises to 2.4× or more, without any change in underlying VC portfolio performance.

That small difference compounds. Imagine a $35 million seed fund paying its usual fees, leaving around $28 million in initial checks. If it recycles $7 million from early wins, total deployed capital jumps to 106% of the fund; meaning that every dollar now works harder than it did before. Scale that up and you see why the best managers build it into their DNA.

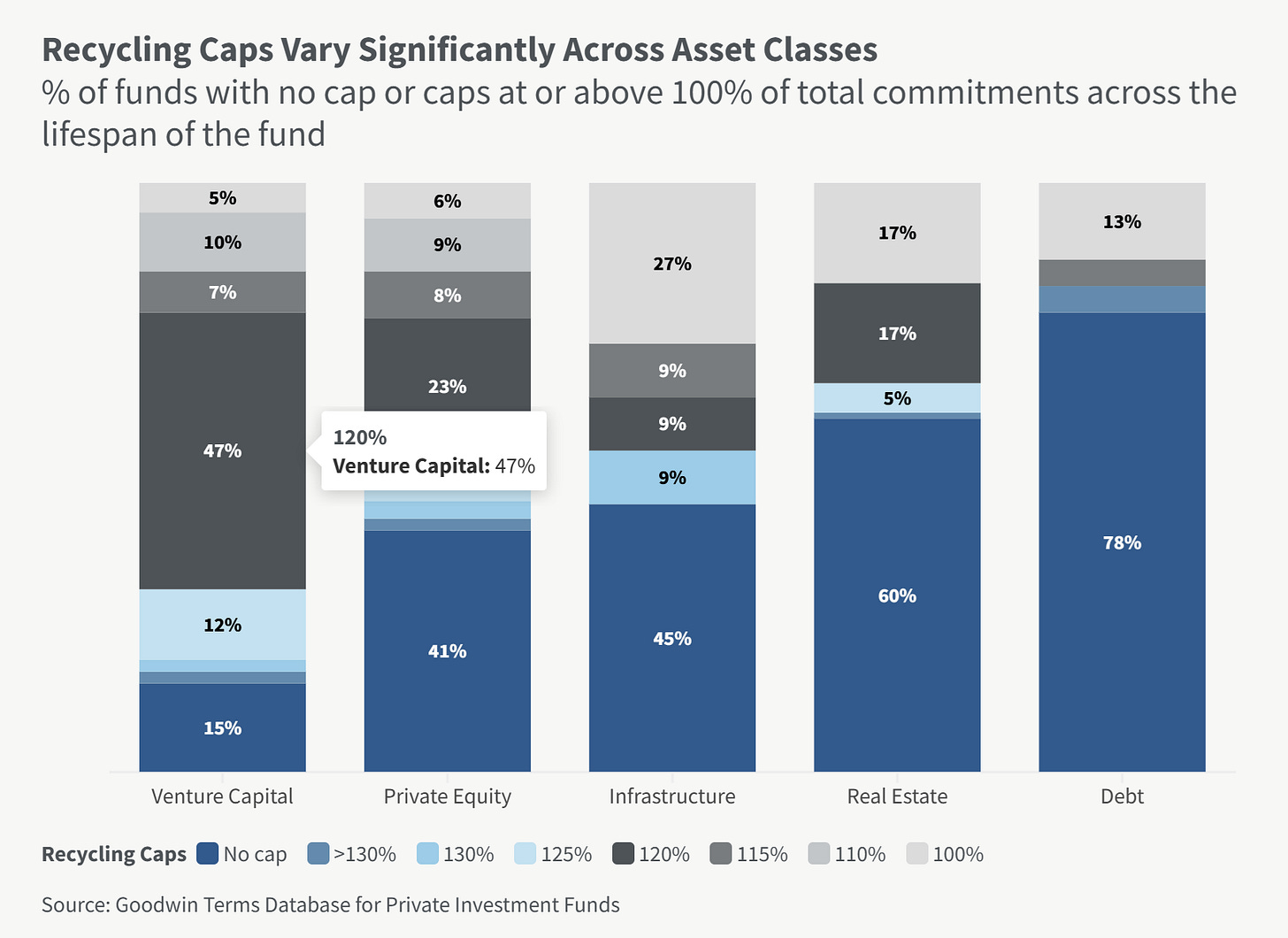

Top funds routinely recycle 110-120% of their commitments. In fact, Goodwin Law’s review of LPA terms found nearly half of venture funds cap recycling at 120%, while some allow unlimited redeployment within the investment period.

The math here makes sense, because if your gross multiple is 3× but fees shave off nearly a third, recycling a portion of those early dollars bridges that loss. It’s a structural fix, one that doesn’t depend on luck, unicorns, or market timing.

Still, few GPs use it aggressively. Some worry it hurts IRR because recycled capital extends fund duration. Others fear LP pushback from institutions that prefer early distributions. And, of course, it demands one thing many early-stage funds rarely have: early exits.

But the data shows that even modest recycling, 10-20% of commitments, consistently narrows the gross-to-net gap.

At its core, recycling is a philosophy of alignment. LPs want their capital working, not sitting idle eaten away by fees. GPs who recycle signal that discipline. That they’re willing to do the harder, less glamorous work of turning early proceeds into additional upside instead of just booking a DPI headline.

It’s not flashy and it doesn’t fit neatly into a fundraising slide. But in a world obsessed with chasing the next unicorn, recycling is one of the few tactics that mathematically guarantees both sides - GP and LP - end up closer together. And that, in venture, that is rarer than a 10×.

5. Fund Size: Why Smaller Funds Punch Above Their Weight

At a certain scale, a VC fund stops being a venture and starts being a beast; not because it’s more powerful, but because its target becomes mathematically impossible. That’s what Josh Kopelman’s “Venture Arrogance Score” (VAS) warns us about.

Some funds are simply too big to behave like true venture vehicles.

The Venture Arrogance Score: A Reality Check

Kopelman defines the Venture Arrogance Score (VAS) as the fraction of total startup-exit value a fund must capture to hit its return targets.

In simpler terms the formula shows how much of everyone else’s upside you need to own to make your fund work. If that percentage is absurdly high, then you’re living in delusion.

As Kopelman’s framing goes, a $7B fund aiming to own 10% of portfolio companies would need to capture 50% of all exit value in its investing window; something no firm has ever done.

He argues that real, repeatable VC funds rarely exceed a VAS of ~10%. A VAS above 10% is essentially a red flag. You’re no longer doing true venture math, you’re playing scaled private equity under a VC brand.

When you see fund sizes like a16z raising $20B, the math becomes grotesque. To hit even modest multiples, those funds would have to siphon off disproportionate slices of all startup value; in effect, owning most of the upside in the market. That’s just not how competition works.

Performance Data Favors Small Funds

The empirical record supports the VAS warning. The majority of top-performing VC funds over the past decade are surprisingly modest in size.

It’s been observed that 91% of top-decile funds in past vintages had assets under $250M (i.e. sub-scale by many institutional standards). About 73% of top funds were Fund I or II.

In some vintages, the median top-decile VC fund size was ~$38M, while median top-quartile size hovered at ~$65M.

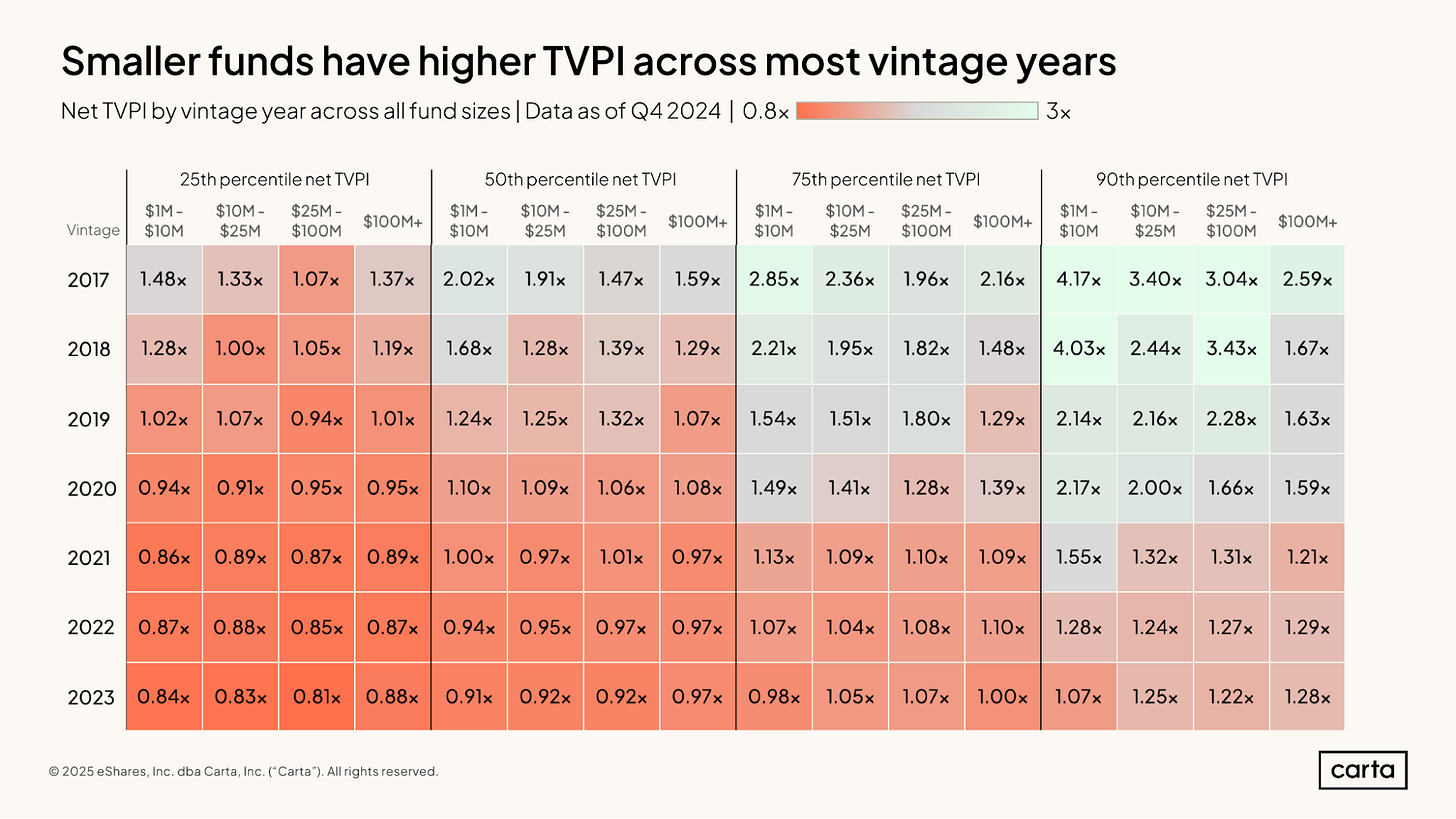

Carta’s performance report similarly notes that among the upper tiers, smaller funds often post the best returns. For the 2018 vintage, funds sized $1M-$10M had 90th percentile TVPI of ~4.03×, while funds above $100M had 90th percentile closer to ~1.67×.

These numbers aren’t coincidences. They reflect deeper structural truths: smaller funds write earlier checks, capture meaningfully higher ownership, and don’t carry the burden of “needing five unicorns to move the dial.”

Why Size Works Against You

The size paradox is that if you raise $500M, you don’t just need more winners, you need outsized exits multiplied. A single billion-dollar exit that might return 10× for a small fund barely nudges a large one. The ownership math gets stacked against you.

Large funds can still win in absolute dollars; they may generate more total profit, but their multiples are structurally capped. Their VAS forces them to demand mega-exits, and when those don’t materialize, performance compresses. It’s a version of diminishing returns at scale.

Good LPs know this already. When they back a mega-fund, they’re often buying stability, not upside asymmetry. They accept that the returns might be lower multiples but more predictable.

For top VCs daring and multiple hunting, the real action lies in the nimble, focused funds that don’t have to hunt five unicorns, just one or two.

6. The Fund Math Playbook (What Actually Works)

You can spend months perfecting a fund model. You can raise with conviction, quote benchmarks, and still end up underwater because the math didn’t care about your story.

After enough vintages, you stop theorizing and start carving a few truths into stone. These are mine. They’re not elegant, but they work.

1. Start small enough that one outlier can return the fund.

If one company can’t pay back your fund, it’s already too big. You don’t get partial credit in venture.

A $50 million seed vehicle that lands 10% in a unicorn can live to fight another day; a $500 million fund with the same exposure just gets a good quarterly update. Venture fund math rewards humility in size.

2. Target ownership that makes the outlier math real.

Your returns aren’t driven by logos, they’re driven by ownership. That 2% allocation in a “hot” $40M post round looks good on paper and bad in an LP letter.

Be the investor who walks away when the entry price kills the math. Every point of ownership you give up is a multiple you’ll never see again.

3. Assume 50-60% of your companies go to zero.

Don’t worry, you’re not broken if that happens. That’s actually the norm. And every dataset we’ve seen earlier says so.

But it’s what you do with the few survivors that defines you. Plan your portfolio around failure, because that’s how you build one that survives it.

4. Expect one or two names to carry you.

You might tell yourself otherwise in Fund I; that five or six good outcomes will do it. But they won’t.

In every 5× fund I’ve ever seen, venture ownership and outliers follow the same pattern: one company did 90×, another 25×, and the rest broke even at best. The portfolio didn’t “balance out.” It got carried. So stop pretending the middle matters.

5. Reserves: concentrate or don’t do them. Never spray.

This is where most funds bleed out. A proper VC reserve strategy sounds noble until you’re “pro-rata-ing” into mediocrity. Laura Thompson at Sapphire Ventures proves that by scattering your follow-ons, your multiples are lowered.

Either double down where conviction is earned or don’t follow at all. Anything in between is self-delusion with better optics.

6. Recycling: pre-plan it, and actually do it.

Don’t wait for your first distribution to think about recycling capital. Bake it into your model pro-actively.

Every great fund I’ve seen recycled around 110-120% of capital. It’s the cleanest alignment mechanism in the business. It means less fee drag, more capital at work, more LP trust. Don’t gift your upside to fund expenses.

7. Be honest about your access.

You know where you stand in the food chain. If you’re late to a round, stop pretending you’re not. Your advantage then becomes price discipline. Don’t chase the brand-name deal at the wrong entry. Because by overpaying once, the math will never forgive you.

8. Show LPs “from-here MOIC” on every follow-on.

Don’t tell your LPs what you hope a company will return. Instead, show them what it’s worth from this point forward. “From-here” MOIC is the only honest measure of judgment. It proves you’re thinking like a capital allocator and not a hype-chaser. LPs respect that more than optimism.

Fund managers are expected to make different mistakes, but the math will punish them the same way. Get these eight things right, and you’ll build something real. You’ll build a fund that’s small, sharp, disciplined, and maybe, just maybe, lucky enough to find the one company that returns it all.

7. Respect the Math, Or the Math Will Humble You

You can have judgment, pattern recognition, and hustle; but it’s the numbers that hold the pen.

And although math doesn’t guarantee success; it defines the boundaries of what’s possible. Inside those boundaries, execution decides the outcome. Outside them, you’re just rearranging hope.

Every GP learns this the hard way. The ones who ignore venture fund math eventually get punished, sometimes slowly, sometimes all at once. The portfolio looks fine until one bad exit, one over-valued follow-on, one diluted outlier exposes what was always true: the model never worked. That’s when LPs go quiet. The next raise stalls. The spreadsheet finally tells you what the story wouldn’t.

LPs learn it the hard way as well. They walk into a fund expecting a 5× and walk out holding a 2×. Too many decks promise power laws without respecting what those laws actually imply: concentration, discipline, humility. When the math’s off, even good managers become passengers to variance.

And founders, whether they realize it or not, live under the same arithmetic. Their investors’ pressure, pacing, and reserve behavior all trace back to these equations. When a GP pushes for markup, dilution protection, or quick follow-ons, it’s rarely personal; it’s the portfolio model trying to survive gravity.

And we can’t say this enough:

In venture, you can’t cheat the math. You can only respect it.

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot. It's amazing how much of what we perceive as 'gut feeling' or 'luck' in business are actually rooted in very precise, albeit often hidden, mathematical models. I wonder how AI will further refine these initial mathematical frameworks, making the 'baked-in' outcomes even more predictable and less about human intuition, for better or worse.

How can founders find out when they’re pitching to a VC? Should they?