The Price Jensen Huang Chose to Pay To Build NVIDIA

What Jensen Huang’s approach to work reveals about building something that lasts.

Lessons From Jensen Huang’s Work Ethic

When we talk about founder work ethic, people treat effort as a virtue, as something they admire, but relentless effort also brings consequences.

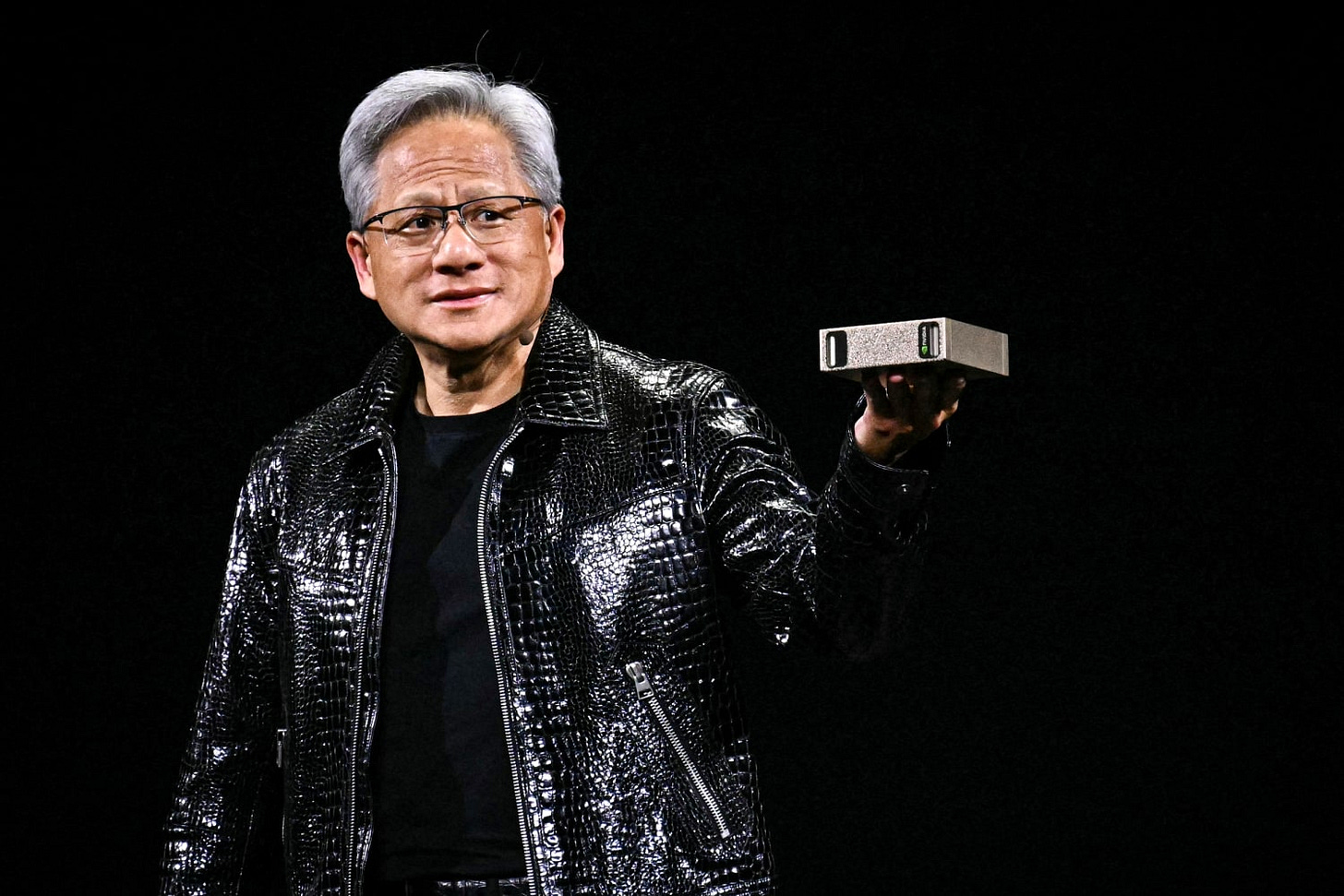

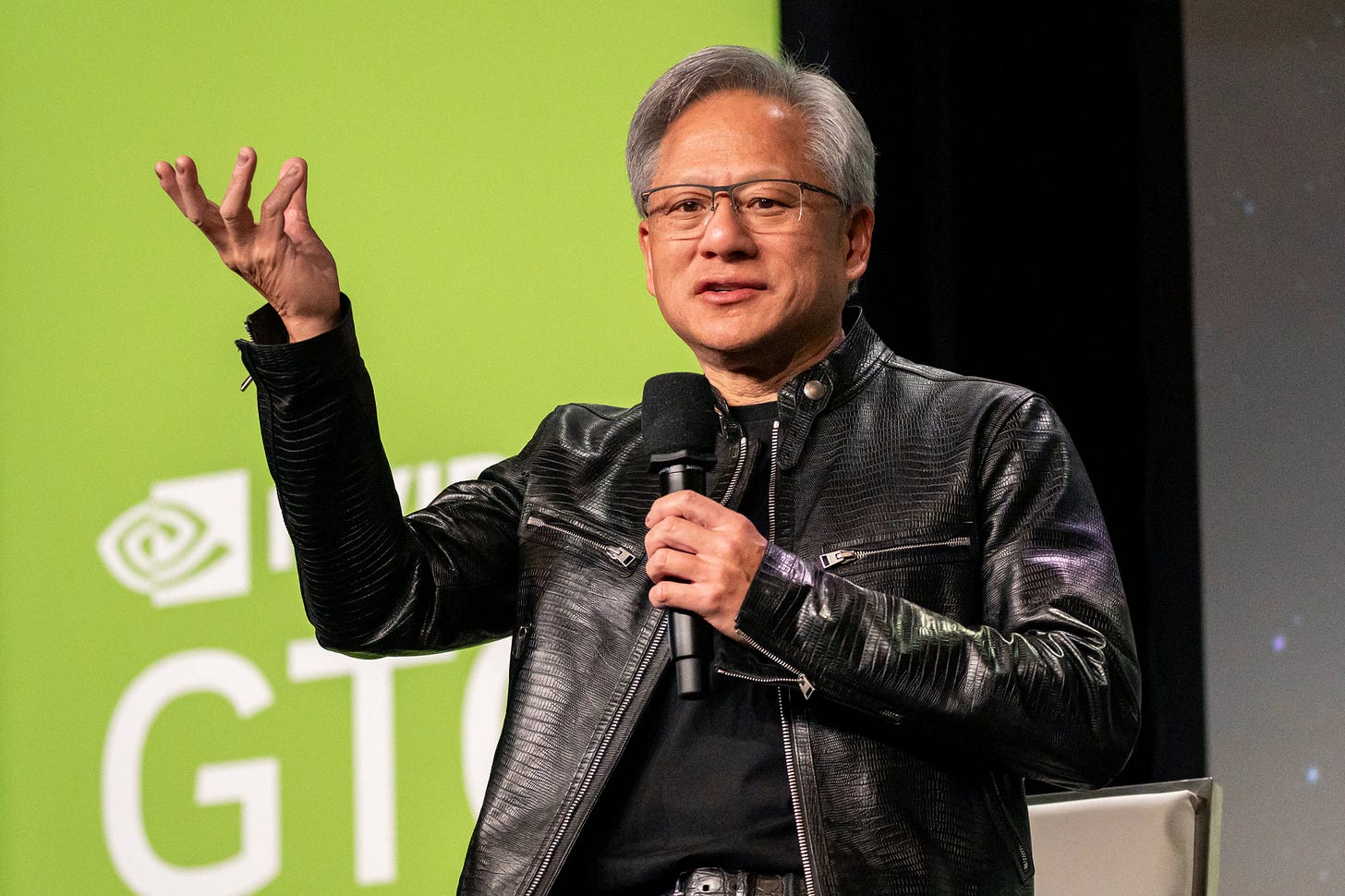

And what better example to use than Jensen Huang, the CEO of NVIDIA. His work is based on a system that affects decision speed, tolerance for pressure, and the kinds of people who survive inside his now-trillion dollar giant.

NVIDIA’s leadership and culture are shaped by the endurance, intensity, and tradeoffs its long-tenured CEO deliberately accepted over decades.

Table of Contents

1. Work as a Default State, Not a Schedule

2. Setting the Pace Through Example, Not Policy

3. Pressure as a Tool for Skill and Character Formation

4. Endurance Beats Talent Over Long Time Horizons

5. Ruthless Prioritization of Cognitive Energy

6. Refusing to Delegate Understanding

7. Craft Over Comfort, Time Over Speed

PS: While writing this, I kept thinking about how much easier it is now to go from idea to something real. So I reached out to the team at Lovable to see if we could make that experience accessible to readers here.

A recent example says it better than I could. Three students in Stockholm were running paid ads that worked, but understanding why stopped scaling. They built Stardust, an AI that analyzes thousands of ads like a human marketer would.

They hit €100K ARR before the product existed, €500K ARR eight days after launch, and have since raised €1.7M pre-seed.

They built it entirely on Lovable.

I asked the Lovable team if we could do something simple for this community, and they set up an exclusive 20% discount so you can try building without friction.

1. Work as a Default State, Not a Schedule

Descriptions of Jensen Huang’s work ethic often revolve around the hours he puts in, as if the defining feature were how late the lights stay on. But this misses the substance of how he actually operates.

What distinguishes him is not time spent at a desk, but an inability and an unwillingness to mentally disengage from the company’s problems. NVIDIA’s unresolved questions do not sit in calendar meetings. They occupy his attention continuously, constantly affecting how he thinks while walking, traveling, or listening.

Work, in this sense, is not something he enters and exits, but a default state of ownership.

Ownership Without an Off Switch

For the CEO of NVIDIA, responsibility is not episodic. It does not spike during crises and then recede. The harder burden is carrying unresolved decisions, weak signals, and second-order consequences over long stretches of time without relief.

NVIDIA’s problems live rent-free in Jensen’s mind because he believes that delegating awareness is the fastest way to lose contact with reality. But that belief carries a cost. It narrows personal bandwidth and makes rest conditional, but it also compresses feedback loops in ways most leaders never experience, because the person setting direction remains exposed to its consequences.

This is what leadership at NVIDIA looks like. Decisions are not handed off cleanly once made. They are revisited and stress-tested as conditions change, and the organization learns that thinking does not end when a meeting does. It continues until the problem itself gives way to a harder one.

Duration Over Intensity

This is where the difference between long hours and persistent cognitive responsibility becomes clear. Hustle culture assumes a sprint followed by recovery. But Huang practices duration.

He works on the assumption that the most important questions will take years to clarify, that inflection points arrive slowly, and that advantage compounds only if attention stays anchored long after novelty fades.

That expectation filters people. It attracts those who are willing to carry weight without immediate payoff and repels those who need clean boundaries between effort and identity.

This filtering is foundational to NVIDIA’s culture. While many tech CEOs treat scale as permission to step back, Huang treats scale as an expansion of the surface area he must personally understand.

There is a cost to this choice, but the benefit is more enduring. Continuity of thought, strategic coherence, and an organization trained to live inside problems long enough for real advantages to emerge.

2. Setting the Pace Through Example, Not Policy

Expectations at NVIDIA are set in the open. Huang does not expect the organization to operate at a pace he is unwilling to carry himself. The person at the top absorbs more pressure, not less, and that becomes the reference point.

Effort and standards are visible. People do not adjust because they are instructed to, but because the alternative is choosing not to belong to a system where that level of commitment is normal.

Intensity as Enforcement

This is where many discussions of founder work ethic go wrong. They frame intensity as motivation, something meant to inspire discretionary effort. In practice, Huang’s personal intensity functions as enforcement.

By outworking the organization, he removes the moral ground on which resistance usually stands. Complaints about pace or pressure lose credibility when the CEO is visibly absorbing more strain than anyone else. Work ethic becomes a statement:

This is the cost of being here, and it applies first at the top.

That dynamic creates a form of authority policies cannot replicate. It does not rely on consensus, and it does not ask permission. The model is explicitly non-democratic.

Expectations are set by example, and there’s no room for negotiations.

Why Complaints Don’t Change the System

In cultures built this way, complaints about workload rarely change outcomes because they do not engage with the underlying premise. Responsibility expands to match the ambition of the mission and not the preferences of the individual.

When leaders lower expectations in response to discomfort, they undermine the very standard that gives the organization coherence. Huang avoids that trap by anchoring demands in his own behavior. The standard is high, because that’s where the leader maintains it.

3. Pressure as a Tool for Skill and Character Formation

Many leaders speak about growth as if it were the byproduct of encouragement or alignment. Jensen believes that meaningful development, whether personal or organizational, emerges from sustained difficulty that does not resolve quickly and does not soften to protect comfort.

In this model, pressure is not a side effect of ambition but an intentional tool used to expose weak thinking, surface gaps in judgment, and force learning to occur under real constraints rather than simulated ones.

Difficulty as a Deliberate Environment

“Torture into greatness” is a phrase attributed to Huang, and it reflects a view that talent without sustained strain plateaus early.

By keeping expectations high and tolerance for sloppy thinking low, NVIDIA creates an environment where problems are not simplified for morale’s sake. Engineers, managers, and executives are expected to wrestle with complexity directly, often in settings where reasoning is visible and mistakes are not hidden.

This approach works only in high-talent, high-expectation environments. People are selected for capacity before they are exposed to pressure. Where that precondition is absent, the same methods would collapse into fear or attrition without learning.

At NVIDIA, pressure functions simultaneously as a filter and a developmental force. Those who remain adapt faster precisely because the system does not cushion discomfort.

Self-Criticism as Anti-Complacency

What makes this system durable is that pressure is not applied asymmetrically. Huang’s standards for others are matched by an internal posture of relentless self-criticism.

He has been open about dissatisfaction with past performance, even during periods outsiders would label as successful. That dissatisfaction works as a defense against complacency, rooted in the belief that success is the most dangerous condition a company can enter.

For the NVIDIA CEO, self-criticism serves a deeper purpose. It keeps attention anchored on what remains unfinished rather than what has already been achieved. It also signals that comfort is temporary and that yesterday’s wins carry no protective value.

Compounding Over Comfort

Sustained pressure can be taxing, and Huang appears willing to accept that cost because the objective is not short-term morale but long-term compounding of skill, judgment, and resilience.

Pressure applied consistently over time changes how people think. It sharpens pattern recognition, increases tolerance for ambiguity, and reduces dependence on reassurance.

At NVIDIA, pressure is treated as an investment with delayed returns. The payoff is not enthusiasm in the moment, but an organization that does not freeze when conditions deteriorate.

4. Endurance Beats Talent Over Long Time Horizons

When Jensen Huang speaks about his own strengths, intelligence is rarely at the top of the list. He has been explicit, sometimes uncomfortably so, about valuing resilience more than raw cognitive horsepower.

Jensen believes that decisive advantages rarely come from having better ideas early, but from staying engaged long enough to find out whether an idea deserves to exist at all. And that’s how endurance becomes a unit of measurement.

Resilience as a Design Constraint

Huang has argued that low expectations increase adaptability because they remove the psychological shock of difficulty.

Leaders who expect smooth progress fracture when it fails to materialize. Leaders who assume friction as a baseline adjust faster when reality pushes back. For Jensen, this posture favors decisions that may look slow or stubborn in the short term, but remain coherent under pressure because they were never built on easy validation.

This stance runs counter to much contemporary rhetoric about founder’s work ethic, which celebrates brilliance and speed. At NVIDIA, patience is not framed as restraint. It is framed as preparedness for prolonged uncertainty, especially when the work involves creating markets rather than competing inside existing ones.

Endurance and the Cost of Market Creation

The clearest example of this logic is NVIDIA’s long commitment to CUDA and accelerated computing. Early signals that GPUs could be used beyond graphics were weak and easy to dismiss. Turning those signals into a platform required years of investment with little external affirmation.

Margins were sacrificed and direction was questioned. Internally, the opportunity remained contested. What sustained the effort was not superior foresight, but tolerance for extended ambiguity.

CUDA was not a clever bet that paid off quickly, rather a slow accumulation of tooling, education, and ecosystem building that only made sense if the organization could absorb skepticism without flinching.

The same pattern appears in NVIDIA’s approach to AI. Long before the narrative hardened, accelerated computing was treated as foundational rather than opportunistic. The market had to be taught, not merely served.

Recognizing an opportunity once it is obvious is common. Remaining committed while it is still unformed and expensive is not.

Why This Is Where Founders Break

Most founders do not fail because they chose the wrong idea, but because they could not stay psychologically invested through the period when the idea produced only friction and criticism.

Endurance here is about engaging actively without reassurance. It’s about the willingness to continue allocating attention and resources while external signals remain negative or noisy.

This expectation is deeply embedded in NVIDIA’s culture. People are not trained to seek early applause. They are trained to assume that meaningful work will feel wrong for a long time before it feels inevitable. Over decades, that training compounds into an organization that does not panic when timelines stretch or narratives shift.

Seen this way, NVIDIA’s advantage is not superior intelligence. It is the capacity, shaped by Huang’s priorities, to tolerate doubt longer than most. That tolerance allows markets to be created rather than chased, and it explains why endurance, not brilliance, sits at the center of how the company continues to build.

5. Ruthless Prioritization of Cognitive Energy

The way Jensen Huang structures his day is often misread as a productivity system, when it is closer to a survival mechanism. He has been clear that he starts with the most important work first, not because it is efficient, but because delaying it degrades judgment.

Attention is the most valuable resource at his level. Once attention fragments, the quality of downstream decisions deteriorates, and no amount of calendar discipline can recover it.

This also explains why prioritization at NVIDIA is not about inbox management or task throughput. Jensen’s highest-priority work usually involves unresolved questions that cannot be delegated cleanly.

These are decisions where context, intuition, and second-order effects matter more than speed. Addressing them early preserves cognitive sharpness for work that cannot be revisited once fatigue sets in. Everything else, including meetings and reviews, is secondary.

This is not an individualistic goal, but a collective one. By resolving the hardest questions first, Huang creates clarity that others can operate against for the rest of the day.

Teams are unblocked not because of his constant availability, but because the most consequential uncertainties have already been reduced. Availability is often mistaken for effectiveness. At NVIDIA, effectiveness comes from sequencing attention so the organization does not stall around decisions only the top can make.

Everyone at NVIDIA knows that urgency is not evenly distributed across tasks. Some work carries disproportionate weight, and postponing it imposes hidden costs downstream.

Prioritization is not about doing more, but preventing the slow erosion of coherence that occurs when leaders defer judgment.

Ultimately, Huang’s approach does not romanticize busyness or constant motion. It treats cognitive energy as something that must be guarded and deployed deliberately, because once it is spent on trivialities, it cannot be reclaimed for work that actually determines outcomes.

6. Refusing to Delegate Understanding

As NVIDIA grew into a giant, Jensen Huang made a choice that most management experts would advise against. He refused to let other people do his thinking for him.

Most leaders at his level rely on polished summaries, colorful dashboards, and layers of managers to tell them what is happening. Jensen decided to stay close to the source. He chose to carry the weight of understanding the messy, unfiltered reality of his company instead of looking at a cleaned-up version of it.

Staying Close to the Edge

For Jensen, knowing the details is a personal responsibility. He doesn’t want the “big picture” if it means losing the truth. He reads raw updates, listens to engineers explain problems in their own technical language, and even attends seminars to learn new concepts firsthand.

Although this makes his workload much heavier, it prevents a common trap. When a leader only consumes summaries, they also inherit the blind spots of whoever wrote them. By doing the hard work of learning things himself, he ensures his vision is based on facts rather than someone else’s opinion.

This deep involvement allows him to notice “weak signals” or tiny patterns that most people would ignore. Big changes often start as small anomalies or strange bugs.

If you are too far removed from the work, you miss these signs until it is too late. By staying engaged at the edges of the company, Jensen can see where the future is headed before it becomes obvious to the rest of the world.

While some might call this micromanagement, for NVIDIA, it is a form of protection. It ensures the person at the top actually knows how the work gets done. It is a grueling way to lead, and it requires a massive amount of mental energy.

However, the payoff is a company that stays grounded in reality. Jensen pays the price of a heavy mental load so that NVIDIA never loses its strategic edge.

7. Craft Over Comfort, Time Over Speed

For Jensen Huang, work is not something to be optimized around lifestyle or balance. He has described it instead as a lifelong craft, closer to gardening than engineering.

A garden rewards patience, attention, and consistency, not bursts of brilliance. You return to it every day knowing progress will be uneven and that neglect, even brief, compounds faster than effort. This metaphor explains why reinvention at NVIDIA is continuous rather than episodic.

The choice to stay with a single company for decades is central to this view. By refusing to move on once success is achieved, the CEO of NVIDIA accumulated compounding context.

Each cycle of reinvention built on scars, misjudgments, and partial wins from the last. CUDA, AI, and platform expansion were not resets; they were extensions shaped by memory. That continuity created an advantage that looks unfair from the outside because it cannot be replicated quickly, regardless of capital or talent.

This is where the NVIDIA culture reveals its deeper logic. Reinvention is not treated as a pivot or a narrative moment, but as maintenance. Markets change, technologies shift, and expectations rise, so the craft demands constant adjustment. Comfort becomes dangerous because it dulls sensitivity to early signals. Speed becomes secondary because rushing breaks the accumulation of understanding that long arcs require.

In the tech world, longevity is often seen as stagnation risk, but at NVIDIA, it became their greatest advantage.

By sticking around for decades, Jensen Huang gained a type of wisdom that can’t be fast-tracked. That is a deep ability to see patterns and reinvent the company before the world forces it to.

There is no moral here and no recommendation disguised as praise. This path extracts a price in time, identity, and sustained pressure. It favors people who find meaning in unfinished work and who are willing to trade comfort for mastery over decades.

It’s a model that clearly works, but it leaves you with one uncomfortable question.

Are you actually the kind of person who could survive living like that?

RESOURCES 🛠️

access all for the next year with a 25% limited discount

✅ The 100 Most Important Pension Funds in the World

✅ 350+ verified platforms where you can post your startup

✅ 153 Startups Fundraising Right Now (And Their DECKS)

✅ RIP SEO: the GEO Playbook for 2025

✅ The Venture Capital Method: How Investors Really Value Startups

✅ IRR vs Return Multiple Explained + Template

✅ The Headcount Planning Module

✅ Synthesia’s deck (got them $180M)

✅ CLTV vs CAC Ratio Excel Model

✅ 100+ Pitch Decks That Raised Over $2B

✅ VCs Due Diligence Excel Template

✅ SaaS Financial Model

✅ 10k Investors List

✅ Cap Table at Series A & B

✅ The Startup MIS Template: A Excel Dashboard to Track Your Key Metrics

✅ The Go-To Pricing Guide for Early-Stage Founders + Toolkit

✅ DCF Valuation Method Template: A Practical Guide for Founders

✅ How Much Are Your Startup Stock Options Really Worth?

✅ How VCs Value Startups: The VC Method + Excel Template

✅ 2,500+ Angel Investors Backing AI & SaaS Startups

✅ Cap Table Mastery: How to Manage Startup Equity from Seed to Series C

✅ 300+ VCs That Accept Cold Pitches — No Warm Intro Needed

✅ 50 Game-Changing AI Agent Startup Ideas for 2025

✅ 144 Family Offices That Cut Pre-Seed Checks

✅ 89 Best Startup Essays by Top VCs and Founders (Paul Graham, Naval, Altman…)

✅ The Ultimate Startup Data Room Template (VC-Ready & Founder-Proven)

✅ The Startup Founder’s Guide to Financial Modeling (7 templates included)

✅ SAFE Note Dilution: How to Calculate & Protect Your Equity (+ Cap Table Template)

✅ 400+ Seed VCs Backing Startups in the US & Europe

✅ The Best 23 Accelerators Worldwide for Rapid Growth

✅ AI Co-Pilots Every Startup & VC Needs in Their Toolbox

“Everyone at NVIDIA knows that urgency is not evenly distributed across tasks. Some work carries disproportionate weight, and postponing it imposes hidden costs downstream.”

definitely a lesson more than for just nvidia! great read thanks.